Writers start as readers. We fall in love with stories written by favorite authors. Often, we seek to write like them. Some of us invent new stories involving favorite characters and settings. That is, we write fanfiction.

Types

Many varieties of fanfiction exist. You could write new adventures, where you take the original work’s characters on fresh escapades within their world. In Fix-it Fic, you write a tale correcting what you see as a flaw in the original work. Author Katie Redefer, for example, wrote Harry Potter fanfiction which depicted a romantic relationship never envisioned by J.K. Rowling. You might consider an update, where many years have elapsed since the original novel and you show older characters, or their descendants, dealing with a new adventure.

Reason

People write fanfiction because they love the original work. They seek to honor it in their own way. Perhaps they feel they lack the literary skills to create their own original story with fresh characters in a setting they invent. Fanfiction requires less creativity, because beloved characters already “exist,” and the world of the story sits ready-made.

Risks

If you write fanfiction for your own private enjoyment, or if you share it with other fans and don’t charge them money, you run no adverse risk.

However, if you write fanfiction based on a work still under copyright protection, and you hope to sell your work, be careful. Some authors allow and even encourage fanfiction. Others sue for copyright infringement.

My Fanfiction

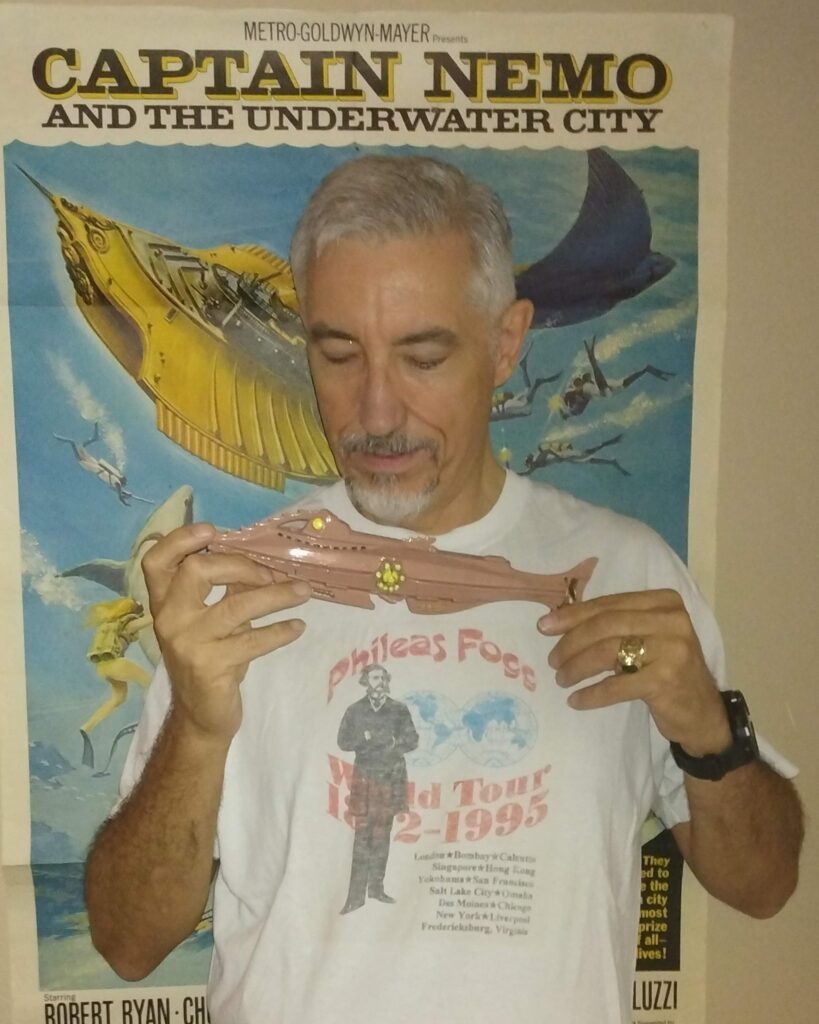

Like many, I started with fanfiction. Years ago, I wrote the first draft of a sequel to Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Seas. I intended to title it 20,000 Leagues Farther. In it, a descendant of Captain Nemo salvages the Nautilus (in modern time) and brings unwitting guests on an adventure-filled voyage. Though embarrassing to recall now, that amateurish novel helped me grow as a writer.

Since then, I’ve written several publishable stories of fanfiction. “The Steam Elephant” honors Verne’s The Steam House by taking his characters aboard their marvelous vehicle to Africa. This story appears in The Gallery of Curiosities #3.

“The Six Hundred Dollar Man” puts an Old West steampunk twist on the TV show “The Six Million Dollar Man.”

In “A Tale More True,” a rival of Baron Munchausen (the fictional character created by German writer Rudolf Erich Raspe) takes a clockpunk trip to the Moon.

My story “Rallying Cry” honors both Verne’s The Steam House and Robur the Conqueror by portraying a secret World War I regiment using two of Verne’s vehicles—-the steam elephant and the aeronef.

In “The Cometeers,” I used the cannon and projectile from Verne’s novel From the Earth to the Moon. My story’s characters must save the Earth from a comet impact…in 1897.

My story “After the Martians” shows the aftermath of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, but WW I occurs using Martian technology.

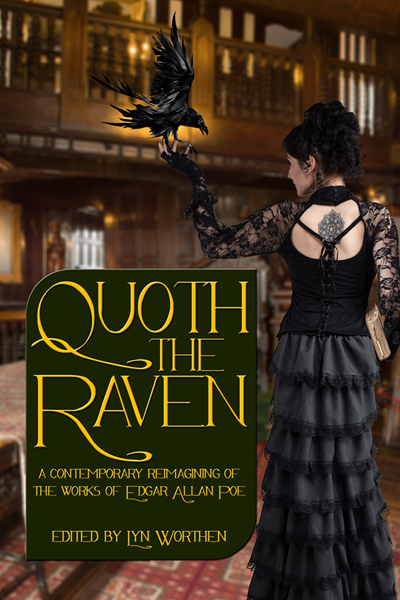

In “The Unparalleled Attempt to Rescue One Hans Pfaall,” (included in the anthology Quoth the Raven) I depict adventurers from Rotterdam flying to the Moon, by balloon, to save a man whom Edgar Allan Poe left stranded there in his The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall.

“Reconnaissance Mission” honors Poe again, making him a character as a young Army soldier who undertakes a mission that would inspire his later stories and poems. This story appears in the anthology Not Far From Roswell.

My story 80 Hours updates Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days by sending a woman to circumnavigate the globe in just over three days.

I may well write more fanfiction in the future, but I feel more confident than I did before about creating my own characters and worlds.

I co-edited two anthologies of other writers’ fanfiction as well. 20,000 Leagues Remembered honors Verne’s undersea masterwork with fan fiction written by today’s authors. The book appeared on the 150th anniversary of Verne’s epic novel.

The North American Jules Verne Society (of which I’m a member) sponsored its own Verne tribute anthology with Extraordinary Visions: Stories Inspired by Jules Verne. This includes recently written short stories honoring many of Verne’s fantastic novels. It’s available in ebook, print, and audiobook versions.

Your Fanfiction

If you haven’t written fanfiction, I bet you’ve been tempted. For people who hope to write fiction someday, fanfiction might serve as a great place to start. The ready-made characters and story “world” simplify the process. Even if you write just for yourself or to give away stories free to fellow fans, fanfiction could provide good practice and a chance to learn the craft and hone your skills.

Get to it. Write! Be like—

Poseidon’s Scribe

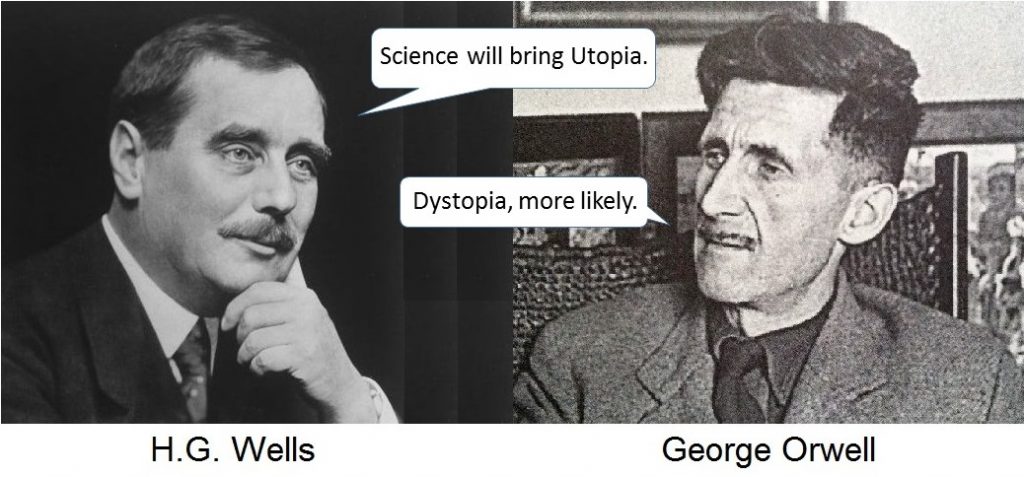

H.G. Wells, best known for his science fiction novels such as The War of the Worlds and The Time Machine, believed science was the best hope for humanity’s future. George Orwell, an essayist, critic, and author of 1984 and Animal Farm, took a less optimistic view.

H.G. Wells, best known for his science fiction novels such as The War of the Worlds and The Time Machine, believed science was the best hope for humanity’s future. George Orwell, an essayist, critic, and author of 1984 and Animal Farm, took a less optimistic view.

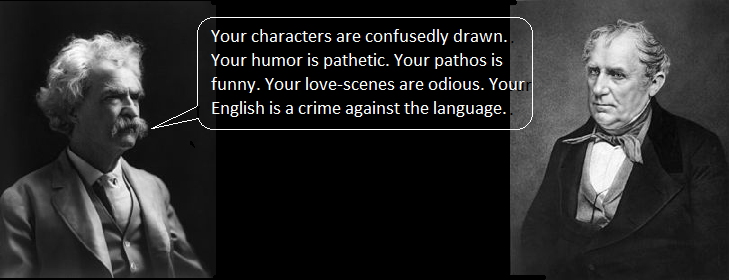

In Twain’s acerbic style, he starts by accusing three Cooper-praising reviewers of never having read the books. He then lays into Cooper, saying, “…in the restricted space of two-thirds of a page, Cooper has scored 114 offenses against literary art out of a possible 115. It breaks the record.” Twain asserts there are 19 or 22 rules “governing literary art in domain of romantic fiction” and says Cooper violated 18 of them. He lists those 18 rules.

In Twain’s acerbic style, he starts by accusing three Cooper-praising reviewers of never having read the books. He then lays into Cooper, saying, “…in the restricted space of two-thirds of a page, Cooper has scored 114 offenses against literary art out of a possible 115. It breaks the record.” Twain asserts there are 19 or 22 rules “governing literary art in domain of romantic fiction” and says Cooper violated 18 of them. He lists those 18 rules.