In a previous blog post, I mentioned Malcolm Gladwell and his book Outliers: The Story of Success. In it, he explored why some people seem to stand out as geniuses in their fields–what made them so good? His conclusion was that success requires two things: (1) Luck, and (2) 10,000 hours of practice.

In a previous blog post, I mentioned Malcolm Gladwell and his book Outliers: The Story of Success. In it, he explored why some people seem to stand out as geniuses in their fields–what made them so good? His conclusion was that success requires two things: (1) Luck, and (2) 10,000 hours of practice.

There’s not much we can do about luck. Gladwell suggested it was a matter of being born at the right time and being exposed to the right influences. When it comes to luck, you either have it or you don’t. If you have it, ride that wave, baby. If you don’t, well, reconcile yourself to the fact that not all books sold are written by the greatest writers of all time. And know this, too: there’s no way of knowing in advance whether you are lucky. Only time will tell.

Although we can’t alter our luck, we can do something about the 10,000 hours. Well, not shorten it, I’m afraid. But we can accomplish it. We can devote ourselves to it. If you spend 10,000 hours honing your skill at one thing, it’s highly likely you’ll become good at it. Perhaps not great, but good. And you may grow to enjoy that activity, such that the idea of the next 10,000 hours doesn’t frighten you, but thrills you.

Gladwell goes on to discuss what the 10,000 hours should consist of. Many of those hours should be devoted to freeform play where failure has a low cost. There should be a lot of experimentation and attempts at trying out different approaches without any external criticism. Examples he gives in his book include hockey players, musicians, and computer pioneers. But you can see how his theory applies to writers.

For writers, the 10,000 hours is spent mostly alone, writing. The freeform play consists of many attempts at stories of different types, many drafts that get discarded, many early tales of poor quality. The 10,000 hours should include some study as well–research into the mechanics of writing, research into how great writers plied their craft.

At this point you might be thinking of examples of great writers who didn’t have to spend 10,000 hours perfecting their skills. Okay, there might be a handful. And you might end up being one. If so, great! But do you really think you should assume that you’re going to be one of that very rare breed that achieves greatness without a lot of work?

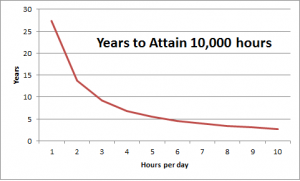

Yes, I’ve done the math. I know that if you can only devote three hours a day to writing, you won’t reach 10,000 hours for over nine years. But for most of us, there’s just no way around that. And you need to remember that much of those 10,000 hours are spent in enjoyable play. It needn’t be all drudgery.

Yes, I’ve done the math. I know that if you can only devote three hours a day to writing, you won’t reach 10,000 hours for over nine years. But for most of us, there’s just no way around that. And you need to remember that much of those 10,000 hours are spent in enjoyable play. It needn’t be all drudgery.

So those 10,000 hours won’t happen by themselves. If you want to be an author, get moving. The clock’s ticking and the calendar’s flipping. Oh, and if you know some sure-fire shortcut, please send it to–

Poseidon’s Scribe