Aliens have come a long way. Not real aliens—I don’t even know if they exist. I’m referring to aliens in literature. Inspired by fine articles authored by Ian Simpson and Joelle Renstrom, I’ll describe how aliens evolved with science fiction.

The Law of Alien Fiction

First, though, I’ll emphasize a non-intuitive law of alien literature: Alien stories aren’t about aliens. They’re about humans. Even stories populated only by non-human characters are about humans. A simple reason explains this—people write stories for other people. If we encounter aliens someday, we’ll write stories about them, and perhaps they’ll return the favor…if they write stories. Until then, it’s all about us.

Origins – Humanoids to Visit and Study

In primeval scifi, aliens resembled us. They served as stand-ins for primitive human societies encountered during exploratory voyages. They existed to be noticed and remarked upon, or to serve as metaphors serving the author’s purposes.

Examples include the sun and moon people of Lucian’s True History, the tall lunar Christians of Francis Godwin’s The Man in the Moone, and the titanic aliens of Voltaire’s Micromégas.

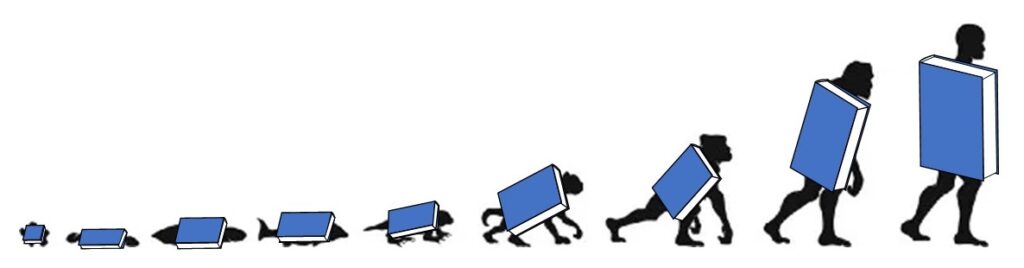

Post-Darwin Evolutionary Branching

Charles Darwin’s Theory of Evolution showed how animal species evolve from earlier forms and sometimes split into two or more species. This freed writers from the humanoid anatomy, so aliens branched out in all directions, exploding into the universe of fiction. They filled all niches. Their attitudes toward humans ranged from bad, through neutral, to good.

We saw warlike, conquest-driven aliens shaped like giant heads in H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds. A variety of species populated Mars in Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Barsoom series. God-like aliens appeared in Olaf Stapleton’s Star Maker. C.S. Lewis gave readers otter-like bipeds and insect-frogs in Out of the Silent Planet. E.E. “Doc” Smith’s The Skylark of Space featured non-material aliens. Arthur C. Clarke showed us Satan-like aliens whose purpose was to prepare humanity for its designated future role, in Childhood’s End. In Starship Troopers, Robert A. Heinlein scared us with huge bug-aliens. By contrast, peaceful and philosophical aliens occupied Mars until humans colonized the planet and displaced them in Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles.

3-D Aliens

Readers loved these aliens, but began asking questions. They wanted more depth. Authors began fleshing out the aliens, thinking through the implications. They gave the aliens backstory, culture, language, politics, art, philosophy, mores, and logical motivations.

In Dune and its sequels, author Frank Herbert supplied a life cycle for the giant sandworms, and integrated them into the values and mythos of the planet.

Larry Niven became the exemplar for fully-imagined aliens, from the puppeteers and Kzinti of Ringworld, to the Moties of The Mote in God’s Eye, to the elephantine Fithp of Footfall (the latter two co-written with Jerry Pournelle). These aliens possessed history, characteristic gestures, distinctive modes of thought, their own behavior patterns—the whole package.

Explanations for Non-Contact

As decades passed and the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) failed to detect evidence of aliens, and as the difficulty of interstellar travel became more apparent, writers found it less credible to craft stories teeming with star-voyaging alien life.

Authors had to confront the Fermi Paradox problem of why humans haven’t heard from aliens, and what forms that communication might take. Carl Sagan’s Contact, Robert J. Sawyer’s Rollback, and Ted Chiang’s “Story of Your Life” examined these themes in different ways.

Your Alien Story

Like time, evolution marches on. I don’t know what’s next for aliens. Perhaps, in an upcoming story of yours, you’ll tell—

Poseidon’s Scribe