A few weeks ago, I mentioned I’d be discussing technology topics in this blog from time to time, along with the accustomed advice for beginning writers. Today I’ll delve into path dependence in technology.

I’ve long found it fascinating how people deal with new technology. Occasionally, developers of a new invention will copy the appearance of an older one. They don’t do this to ease adaptation for the user, but rather to reduce the risk of failure. By starting with something proven, with available parts, and making only a few changes, innovators increase the chance of their invention’s success.

This is the technological aspect of the larger term ‘path dependence,’ since historical precedence frames the inventor’s decisions. Only later does the new invention diverge in form from its predecessor.

You won’t find path dependence in all new technologies, but it’s most often present in evolutionary, versus revolutionary, developments.

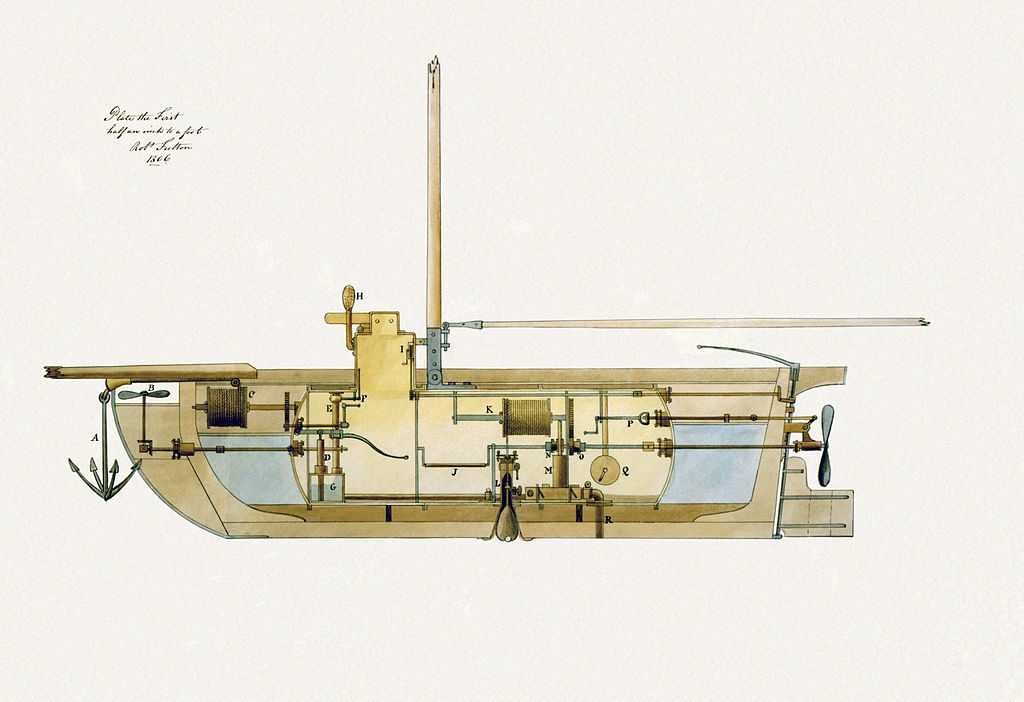

- As a former submariner, one of my favorite examples of path dependence is the shape of submarines. Early submarines intended for long transits, like Fulton’s Nautilus and the military subs of World Wars I and II, resembled surface ships. They had ‘U’ or ‘V’ shaped cross sections, not ‘O’ shaped. Only later did submarine designs deviate from the standard surface ship configuration.

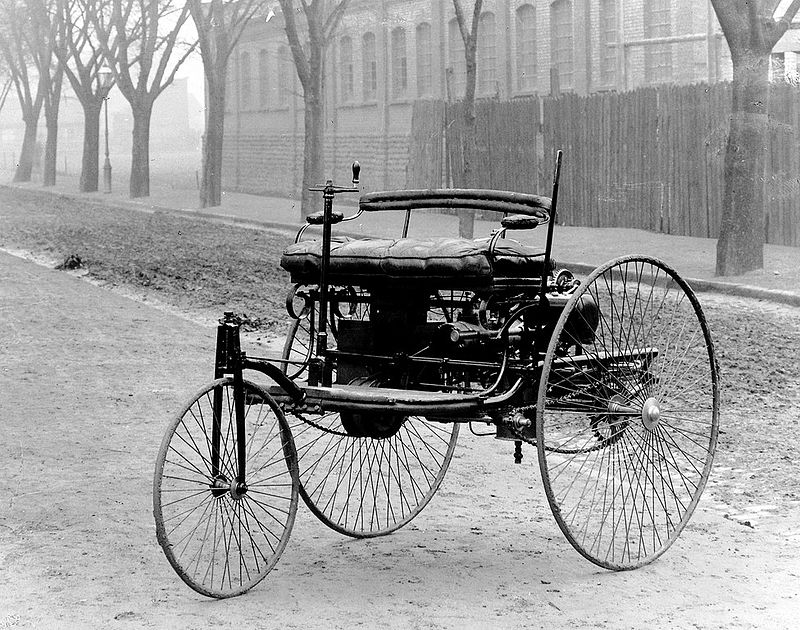

- The automobile is another example. The first automobiles resembled the horse-drawn carriages that preceded them. Subsequent automobile designs departed from this model.

- E-mail is another example of path dependence. The term itself refers back to the postal mail that came before electronic mail. In the early days of e-mail, people also formatted their messages as they had with traditional letters.

I’ll also cite three examples from my own stories. These are all fictional inventions, but are path dependent in the sense that their appearance sprang from predecessor technologies.

- When I came across a claim that someone had invented a prototype submarine in China circa 200 BC, I decided to write a story about that. Accounts of this feat from 22 centuries ago were vague, so that freed me to create my own version. In “The Sea-Wagon of Yantai,” my protagonist inventor, Ning, patterns his submarine after the horse-drawn wagons of the period. I assumed my inventor would make minor alterations to a vehicle type with which he was familiar.

- In writing my story “The Wind-Sphere Ship,” I toyed with the notion that Heron (sometimes written as Hero) of Alexandria might have found a practical use for the toy steam engine he built in the First Century AD, that of propelling a ship. Of course, he wouldn’t have envisioned a propeller-driven ship with an 18th Century style steam engine. My story features an oar-driven galley, with eighteen of Heron’s spinning metal spheres driving the oars.

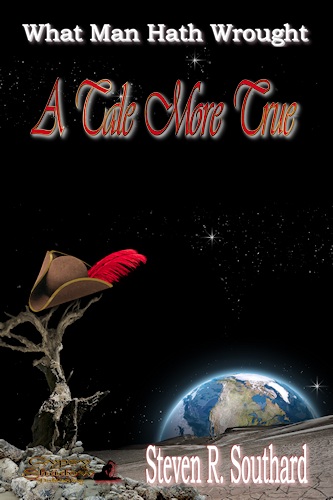

- In “A Tale More True,” my protagonist constructs a gigantic coil spring intended to launch him to the Moon from Germany in 1769. Count Federmann knows nothing of aerodynamics (let alone the effect of acceleration on the human body), so his capsule is merely a small metal house, square in shape, with a pitched roof. Again, this innovator chooses a shape with which he’s familiar.

Do you know of other examples of path dependence in new technology, whether real or fictional? If so, leave a comment for—

Poseidon’s Scribe