Are you one of those who’d like to write a story—a novel, even—but the task seems too difficult? You recall unpleasant memories of Language Arts classes, learning all the complex rules of English. You’re afraid you’ll break a rule.

I’ll simplify things for you. There’s only one rule.

There exist, however, a vast number of guidelines. These cover spelling, grammar, punctuation, sentence structure, plot, pacing, character development, story formatting, manuscript submitting, and more. A lot to keep track of.

Or not.

For every guideline you name, at least one famous author ignored it:

- Don’t use double negatives. Jane Austen didn’t not use them.

- Don’t use run-on sentences. Both Charles Dickens and Marcel Proust thought otherwise, going on and on with long sentences on many occasions, long past the point of necessity.

- Don’t begin sentences with conjunctions. But William Faulkner did.

- Always set off dialogue with quotation marks. Cormac McCarthy and José Saramago said no thanks.

- Use periods and commas where required. James Joyce and Gertrude Stein both famous writers got along okay without them

- Use proper punctuation. Samuel Beckett never did and Junot Díaz never does

How come you had to learn all those guidelines, but famous authors get to violate them? For one thing, guidelines help when you’re learning to write. Also, the guidelines make your writing more understandable to readers. They’re getting what they expect, what they find easy to read.

It’s okay to violate a guideline, but you shouldn’t break the One Rule.

What’s the One Rule?

Here it is: Tell a good story.

That’s it. Or rather, that’s the simplest expression of the One Rule.

What is a ‘good story?’ From a writer’s perspective, I’d say a good story comes from deep within. The writer cares about the story and feels a strong need to tell it.

If the writer does that job well enough, then a good story (1) draws a reader in, (2) keeps a reader reading, (3) leaves a reader changed, and (4) lingers in the reader’s mind long after reading it.

If you write a good story, it doesn’t matter how many guidelines you violate.

Let’s say you’re in the middle of writing a story. Words are flowing, straight from your heart. You’re in the zone.

You stop. Some inner editor, some memory of a Language Arts teacher, or some recollection of an authoritative website’s advice, berates you for breaking a rule. Looking back over your manuscript in horror, you realize it’s true. You’re a language criminal. The linguistic police will apprehend you and send you to writer jail.

Before the law can close in, you hide the evidence. You change the story, bringing it into compliance with the rules. From somewhere inside, a rebel voice protests, “now you’re making the story worse.”

As you look over what you’ve edited, it’s clear. The voice is right. The story is worse. Not what it was meant to be. As if the story itself wants you to break a rule. Your story demands it.

What to do? Well, many things that seem like hard and fast rules are really just guidelines. If obeying them would worsen your story, ignore them.

That last part—that ‘if’—is key. Violate a guideline only after consideration, not out of ignorance.

Just don’t break the One Rule. Tell a good story. In the pursuit of that goal, you may violate any other guideline, with the full permission of—

Poseidon’s Scribe

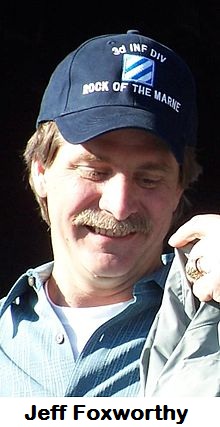

Do you have what it takes to be a writer? If you did, would you know you did? Sometimes it’s difficult to tell. To make it easy for you, I’ve developed a handy test along the lines of Jeff Foxworthy’s ‘Redneck Test.’ See how many of these apply to you.

Do you have what it takes to be a writer? If you did, would you know you did? Sometimes it’s difficult to tell. To make it easy for you, I’ve developed a handy test along the lines of Jeff Foxworthy’s ‘Redneck Test.’ See how many of these apply to you.