You populate your stories with a full cast of characters and expect readers to keep them all straight. Asking a lot, aren’t you? Today, I’ll explore ways to make that task easier for your audience, those kind folks who shell out money for your books.

Source Unknown

Though I try to credit my sources, I’ve misplaced the inspiration of this information. I subscribe to newsletters from DreamForge Magazine and one item from over three years ago prompted me to take notes. Now I can’t find the original newsletter. In any case, I’ve put the advice in my own words and added items to the list.

Pair Description with Action

You need to describe your characters, of course, and physical appearance plays to the primary sense—sight. You’d do well to appeal to the senses of sound and smell, too. But a paragraph weighed down with description slows the story’s pace. Consider sprinkling in the description verbiage with action. Examples:

- “No!” Her long, brown hair swished as she turned and stomped away. “I won’t do it.”

- Jake used his long arm-span to advantage, sweeping his knife to keep his adversary’s slashes out of range.

Be Specific

Edit out generalities and replace them with concrete terms. Appropriate similes and metaphors can serve you well here.

- Instead of “He looked, in a word, handsome,” use “His physique would prompt Michelangelo to destroy David out of shame.”

- Instead of “She was strong in every sense of the word,” use “She could have bench-pressed a life-size marble statue, then won a stare-down contest with it.”

Use Revealing Traits

Often a character’s physical appearance or mannerisms can indicate a characteristic emotion or internal conflict. This falls in line with the “show, don’t tell” adage. The Emotion Thesaurus by Angel Ackerman and Becca Puglisi can aid you here.

- Instead of “He seemed perpetually afraid,” use “He huddled in corners, sweating, trembling, and avoiding eye contact.”

- Instead of “She looked okay, but I could tell something troubled her,” use “She paced back and forth, frowning, and running a hand through her hair.”

Provide Distinctive, Identifying Traits

Consider giving each significant character something that sets the character apart. It could be an unusual hairstyle, an item of clothing, a scar or other imperfection, an atypical gait, a characteristic gesture, an odd verbal expression, or anything in a near-infinite list. I won’t provide examples here, but you get the point. Every now and then, when that character appears in the story, mention that specific trait to jog your reader’s memory of that character.

Add a Weakness

Give your character a flaw, a weakness, a vulnerability. As a minimum, your protagonist needs one, if not all your major characters. Later in the story, let your antagonist test the protagonist’s weakness and exploit it in some way.

Don’t Forget Motivation

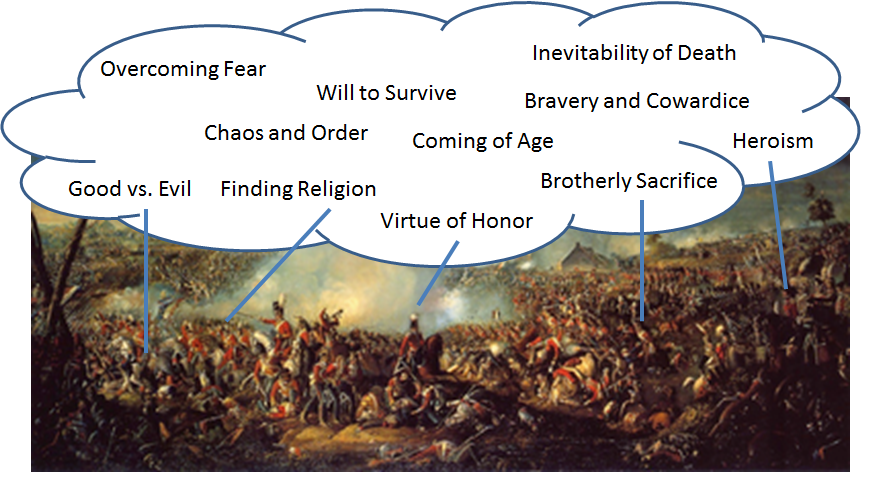

Give each major character a motivation. You may select from a large number of these, including love, revenge, greed, survival, etc. For your protagonist, consider showing why the character feels that motivation. Perhaps it springs from a formative childhood experience. That motivation should tie in to the protagonist’s goal. Don’t confuse goal with motivation. Goal is what you want. Motivation is why you want it. Together, the motivation and goal of the main character drive the plot along.

Assign the Right Name

Spend some time thinking of the right name for your characters. I’ve blogged about this before. An unusual name can set a character apart and help a reader remember the person. A common name can identify the character as an “everyman.” Two characters with similar names, especially with the same first letter, can cause readers to mix them up. Names that resemble a word can help a reader associate a character with that word, whether the word is appropriate for that character or diametrically inappropriate. You can also use the syllabic rhythm of the name (first-last or first-middle-last) to suggest something about the character.

If you apply the above techniques, you might create characters almost as distinctive as—

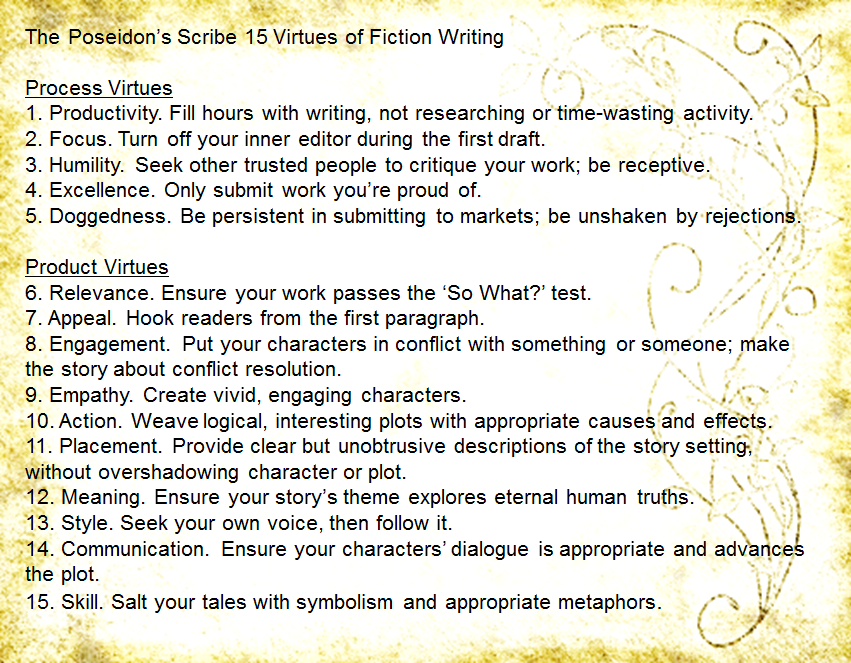

Poseidon’s Scribe