Want to write a best-seller? Together, you and I will figure out the secret.

As I’ve posted before, data scientists have developed software that can predict whether a novel will be a best-seller. These text-analyzing tools are about 84% accurate, but only work when they have text to analyze. That is, you have to write the book first, and then run it through the computer. Not super helpful.

We can do better than that, at least as a mental exercise. W. Somerset Maugham is reputed to have said, “There are three rules for writing a novel. Unfortunately, no one knows what they are.” Let’s figure out the rules Maugham said no one knows, but not just for novels—for best-selling novels.

I don’t know about you, but I’m not a data scientist and don’t know a thing about creating text-analysis software. I don’t have the time or spare cash to buy all the best-sellers for the last few years and input all that text into a computer.

Still, we won’t let minor details stop us. In fact, since we’re creating imaginary software, we’re free from bothersome facts that constrain real data scientists. Our best-seller writing rules needn’t involve things that computers are good at counting. We can come up with any rules we want.

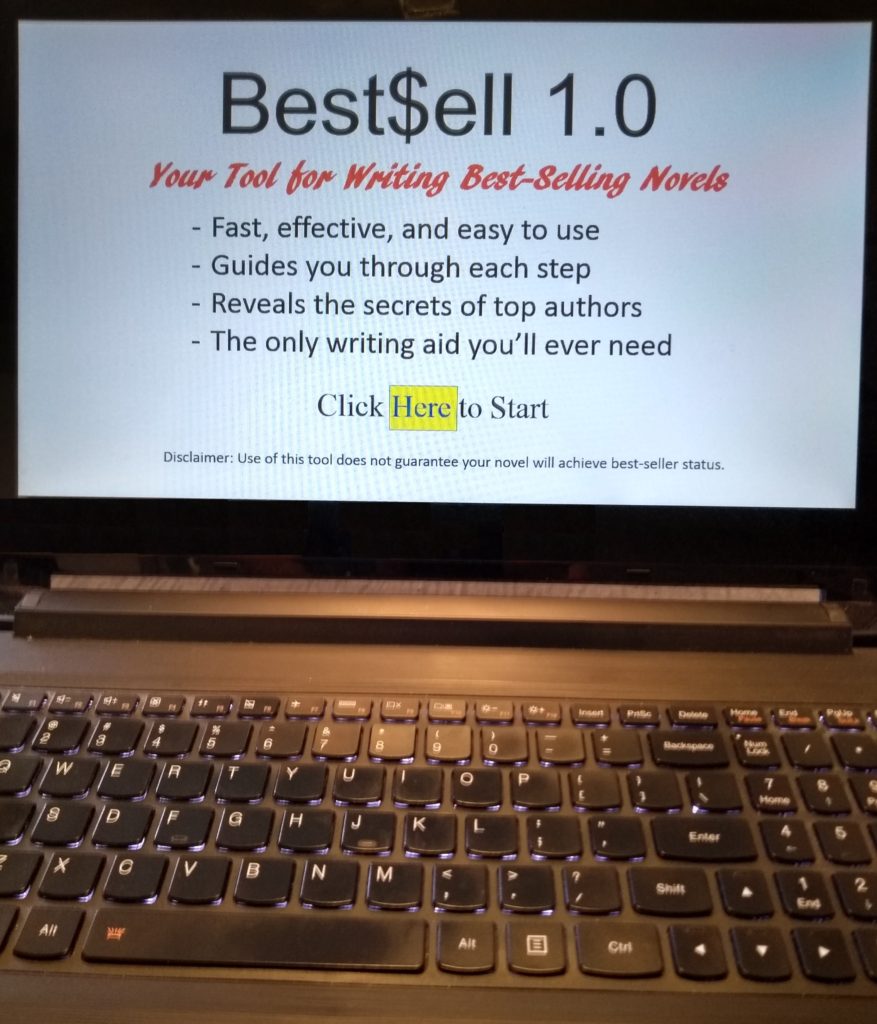

Let’s start with a name for our imaginary software tool. Perhaps Best$ell 1.0. Not very good, but we’ll use if for now and get our Marketing Department to work on a better name.

Let’s imagine a list of attributes that Best$ell 1.0 will use. We’ll use this list for starters:

- Luck

- Amount of promotion of novel

- Appeal of book cover

- Existing fame of author

- Appeal of main characters

- Difference from other novels

- Addresses a current or emerging topic

- Addresses a controversial or taboo topic

- Amount of sex or violence

- Quality of prose

You could come up with different attributes, but that list should be okay for Version 1.0. Let’s say Best$ell 1.0 can easily measure all of those attributes. Let’s also say a greater amount or degree of any of those attributes gives a manuscript a better chance of becoming a best-seller.

Looking back over our list, I see one problem. Some attributes are beyond the author’s control. The first one depends on chance. The publisher controls the second one, for the most part. Attributes 3 through 5 depend on reader reaction. Attributes 6 through 8 depend on society in general.

I put the list in rough order from least author control to most author control. The author has some influence on all the attributes except number 1, but has greatest control over the latter items in the list.

Moreover, not all the attributes would be equally important. Best$ell 1.0 would know the weights to assign to each attribute, of course, and it may well be the last items in the list outweigh the first ones. That would give the author greater influence.

Of course, that last attribute might be fully under the author’s control, but it’s not a very actionable attribute. How, exactly, do you write high-quality prose?

Well, it looks like Best$ell 1.0 has a few bugs and isn’t ready for release. But it’s a start. The next version will be much better, given the talent and expertise of our top-notch team: you and—

Poseidon’s Scribe