The more I learn, the more I realize how little I know. I thought I knew something about story plot structures, and even blogged about the subject a couple of times—here and here.

Then I watched a webinar on March 2, taught by writer Madeline Dyer, titled ‘The Art of Narrative Structures.’ She referenced a blog by Kim Yoon Mi, who’s made a thorough study of how to structure stories. One post, in particular opened my eyes.

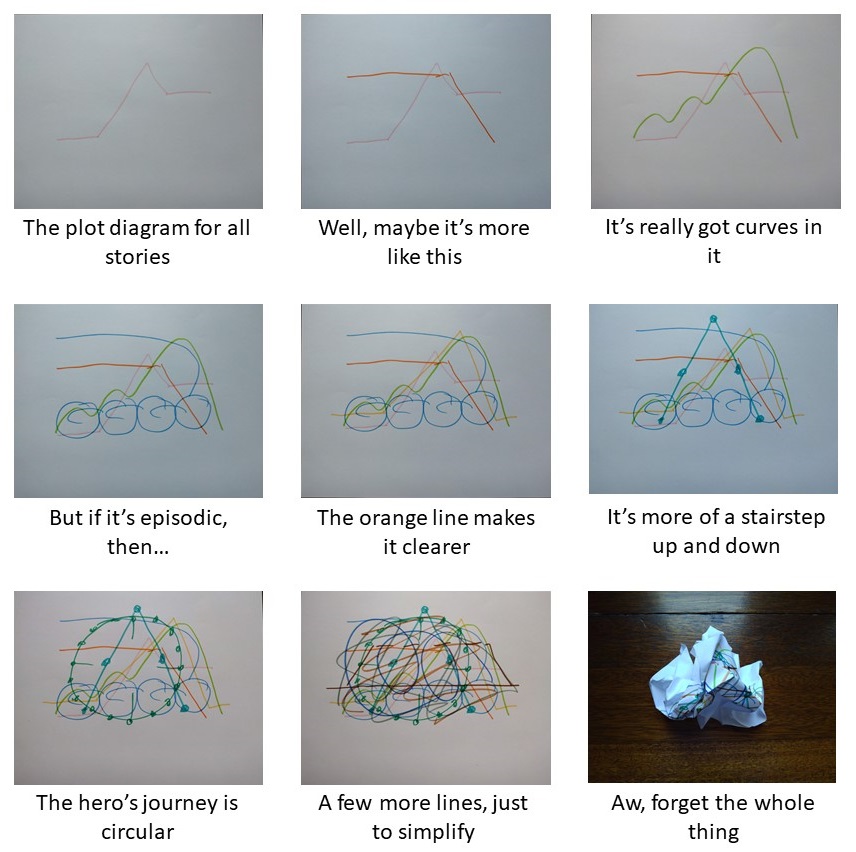

Like many people, I’d taken my cues from Aristotle, with ideas later expanded on by Gustav Freytag. Those ideas resonated, since they comported with the types of stories I’d read all my life, and the TV shows and movies I watched. Between Aristotle and Freytag, they’d pretty much nailed down the way to structure any story.

Nope. Not even close.

Kim Yoon Mi lists 26 different story structures. These include many I hadn’t heard of, such as the Bengali Widow Narrative, Bildungsroman, Crick Crack, Griot, Hakawati, Jo-Ha-Kyu, Karagöz, Robleto, and Ta’ziyyah. She admits there are even more she hasn’t studied yet.

It’s clear there’s more than one way to tell a story. Kim Yoon Mi asserts that the Aristotle/Freytag methods over-emphasize conflict. I’ll have to study and think more about telling a story without emphasizing conflict.

Her main point is that a story must evoke an emotional response in the reader, or make the reader think. There are many ways to do that. A writer can choose from numerous story structures to achieve that end.

Down through the ages, people in different times and cultures came to prefer stories adhering to certain structures. They came to expect things a particular way, and writers in those cultures delivered. These preferences became unwritten standards, then firm rules.

If the ‘rules’ established in the Greco/Roman/European culture seem so pervasive, it’s not because they’re the one, true way. It’s because they’re the rules passed down to us, but there are many other ways.

The whole idea of making rules for story structures now seems wrong-headed. It puts the focus on the path, not the destination. If the goal is a reader’s emotional response, and many paths lead there, why limit yourself to one?

In theory, a writer could think more about maximizing the reader’s emotional response, and select the best story structure from the dozens available to achieve that end.

In theory. As the philosopher Yogi Berra said, “In theory there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice there is.”

A writer who feels free to pick any story structure faces two obstacles—editors and readers. Editors and readers belong to whatever time and culture they’re in. As stated before, they’re used to stories being written a certain way. An editor may not accept your story if it strays too far from the norm—the rules. If it does get published, readers might not enjoy it.

Still, rules are meant to be broken. Traditions get challenged all the time. Editors and readers sometimes become fascinated with the new and different, or something old that seems new to them.

Nothing wrong with trying out a different plot structure. Learn something new. Never assume that the font of all knowledge is—

Poseidon’s Scribe