Here’s a dystopian YA novel you’ll want to check out: Star Touched, by A.L. Kaplan. It contains fascinating characters, a challenging future world, and themes sure to interest teens and adults alike. Isn’t the cover intriguing?

The book immediately immerses you in Tatiana’s world, eight years after a meteor has wiped out much of the Earth’s population, and civilization is back to Nineteenth Century technology levels, without electricity. People struggle to grow food and survive in scattered cities, now walled to keep out invaders. While some work hard to restore good relations and a semblance of civilized society, others scheme at ways to take advantage of the weak.

The meteor did more than kill; it also left a small minority of people and animals “star-touched” with strange powers that are difficult to control. Eighteen-year-old Tatiana is one such person, along with her small dog, Fifi. Tatiana has lost her family and gone roving, finally settling in the town of Atherton, hoping to be accepted and to work for her food and lodging. Since most people fear and distrust the star-touched, she tries to keep her special powers hidden.

She finds work at an inn run by a kindly owner. But not everyone on the staff treats Tatiana well. Moreover, the corrupt town leaders are forming terrible plans for the future of Atherton. To make things worse, a new religious order is seeking out the star-touched, and Tatiana doesn’t know why.

Burdened by all these difficulties along with a ton of internal guilt over a long-ago death she couldn’t prevent, Tatiana will need to confront all her problems and find out if she has the strength of character necessary to endure.

Aimed at the Young Adult market, this novel touches on themes of being different from others, acceptance, maturity, and friendship. Readers will be perceptive enough to deduce the novel’s real message, a powerful and relevant one: we may not have superhero powers like Tatiana, but each of us is different, with our own special abilities and talents. We shouldn’t have to hide our gifts, and we shouldn’t hate the gifts of others. In a sense, each of us really is star-touched.

When the novel launches in October, I urge you to buy and read your own copy of Star Touched by A.L. Kaplan, published by Intrigue Publishing, LLC. How did I get an advance copy to read for this review? That’s a secret to be kept by—

Poseidon’s Scribe

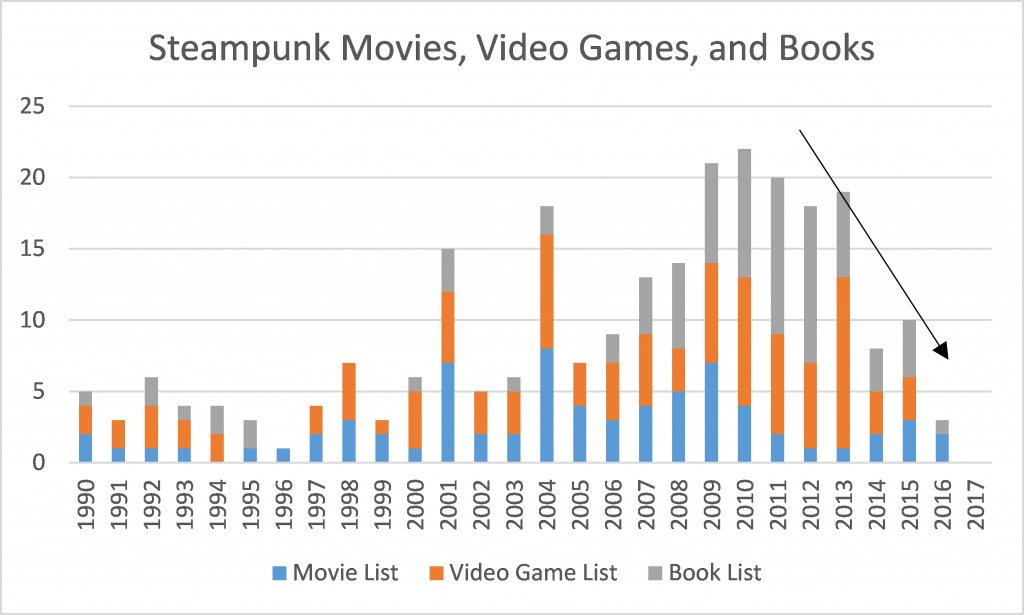

Don’t get me wrong. Steampunk will always be. An enthusiastic minority will forever celebrate it. I’m not saying it’s dead and gone.

Don’t get me wrong. Steampunk will always be. An enthusiastic minority will forever celebrate it. I’m not saying it’s dead and gone. So far I’ve been referring to the story-telling side of steampunk, the part that started the movement. That’s not all there is. There’s a side of steampunk that’s as popular as it ever was—fashion. When it comes to costumes, jewelry, and custom-made gadgets, that aspect remains in full swing, still going strong.

So far I’ve been referring to the story-telling side of steampunk, the part that started the movement. That’s not all there is. There’s a side of steampunk that’s as popular as it ever was—fashion. When it comes to costumes, jewelry, and custom-made gadgets, that aspect remains in full swing, still going strong. You’ve been thinking about your story a long time, plotting it, developing the characters, working on the setting. You have notes, outlines, plot diagrams, and character descriptions up to here. Now it’s time to write, but no words are coming out.

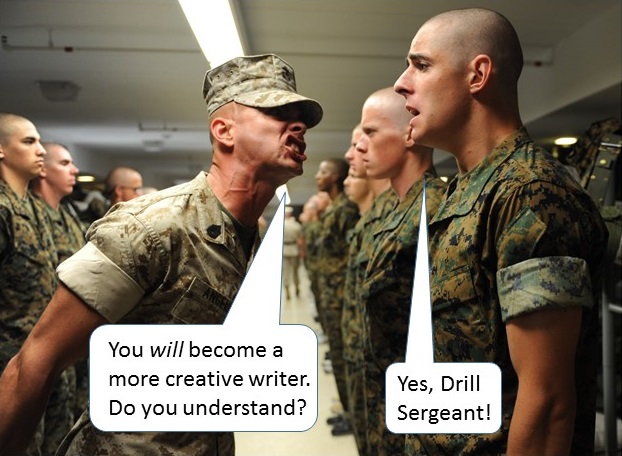

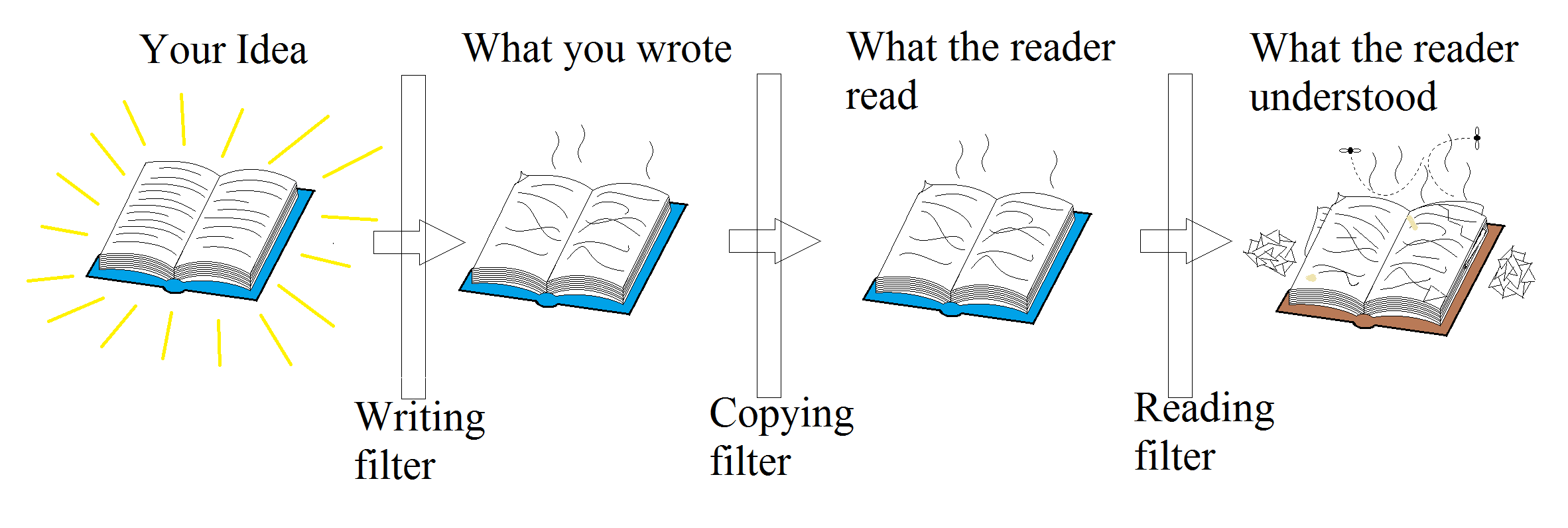

You’ve been thinking about your story a long time, plotting it, developing the characters, working on the setting. You have notes, outlines, plot diagrams, and character descriptions up to here. Now it’s time to write, but no words are coming out. The process is usually not as bad as the way I’ve dramatized it in the accompanying image. Still, it’s a less efficient transmission method than mental telepathy would likely be.

The process is usually not as bad as the way I’ve dramatized it in the accompanying image. Still, it’s a less efficient transmission method than mental telepathy would likely be.