Are you the type of writer who measures progress through word counts? If so, here’s today’s question: how do you measure your progress in the second draft?

I first explored the metrics of writing in this post, but I was thinking of first drafts as I wrote it.

It’s easy to measure progress on your first draft. The manuscript was x words long at the end of yesterday, and y words long at the end of today; therefore, today’s word count is y – x. Any word processor can count those for you. There are several blog posts where you can compare your words/day count to those of many famous authors.

That’s fine for the first draft. There was a blank screen before, and there are words on it now. Easy to see and measure the difference.

What about the second draft, and all subsequent ones? For me, those are the more difficult and time-consuming drafts, and therefore it’s even more important to find a way to measure progress. But despite the crying need for a good metric in these drafts, there doesn’t seem to be a reliable one.

Let’s illustrate the problem with some numerical examples. Let’s say the first draft of your short story contains 6000 words. At this point, you don’t really know how long the finished story will be. That first draft might have been too verbose, so cutting will be necessary. Or you might have left out some key points, so it needs to be longer.

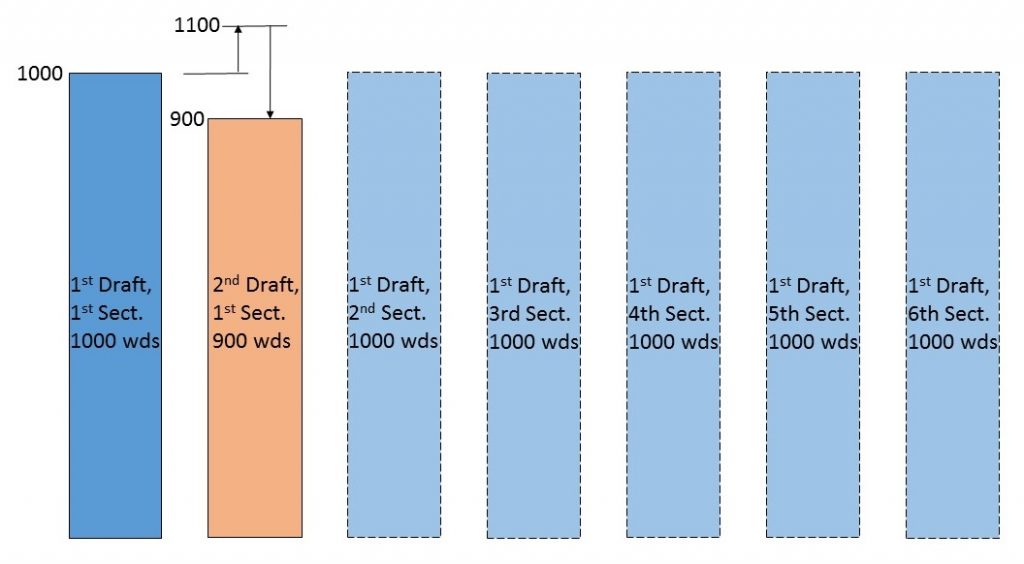

You start the 2nd draft editing process, using whatever technique you’ve grown accustomed to. At the end of the first day of this, you reviewed 1000 words of that first draft. To that, you added 100 words and cut 200. Those 1000 words are now 900 words (1000+100-200), with 5000 remaining to review.

How do you measure the work of that first day of editing?

- Do you count added words as positive, and cut words as negative? That would be -100. On days when you cut more than you add, your ‘progress’ will be negative.

- Do you count the percentage complete for editing the entire story (900 ÷ 6000 = 15%)? In that case, how long do you think the final story will be; what number do you put in the denominator? 6000 was the length of the first draft and most likely won’t be the length of the second.

- Since both adding and cutting represent work on your part, do you add the adds and subtracts together (100 + 200 = 300)? That may not be easy to get your word processor to do.

- Do you count all 900 words as the finished portion of your 2nd draft?

To me, the last option seems the best. It’s easy to get your word processor to count, and does represent completed work on your part. On the other hand, some days, you may not have much editing to do and will nevertheless get credit for quite a bit of work. On other days, you may cut most of what you read, and will end up with very little credit for all that work.

I offer the question up to the wisdom of the web. Comment and let me know how you measure your daily progress through 2nd and subsequent drafts. If there’s one writer you can count on who can learn from others, it’s—

Poseidon’s Scribe

Your muse, like all of them, isn’t the most focused entity around. Easily distracted by new and shiny objects, she comes up with fresh ideas all the time.

Your muse, like all of them, isn’t the most focused entity around. Easily distracted by new and shiny objects, she comes up with fresh ideas all the time. Allow me to define what I mean by censorship. It’s the deliberate alteration of text, without the author’s permission, to make the story less offensive to the censor. This is not what a normal editor does. Editors collaborate with authors to correct errors, to make the book as good as it can be.

Allow me to define what I mean by censorship. It’s the deliberate alteration of text, without the author’s permission, to make the story less offensive to the censor. This is not what a normal editor does. Editors collaborate with authors to correct errors, to make the book as good as it can be.

Sitting at your computer, you produce your first work product of the day. (What’s the product? I don’t know; we’re talking about your current day job.) You e-mail it to your boss and wait. A few hours later, your boss e-mails you back to say the product didn’t suit her needs. She says she can’t accept it.

Sitting at your computer, you produce your first work product of the day. (What’s the product? I don’t know; we’re talking about your current day job.) You e-mail it to your boss and wait. A few hours later, your boss e-mails you back to say the product didn’t suit her needs. She says she can’t accept it.

I didn’t hire a professional photographer.

I didn’t hire a professional photographer.