Pole to Pole Publishing just released a new anthology, Re-Terrify: Horrifying Stories of Monsters and More, and it contains a story of mine, “Moonset.” In that tale, my protagonist must “fight an unbeatable foe,” as in the song “The Impossible Dream (the Quest)” from the musical Man of La Mancha.

For Re-Terrify, the publisher wanted reprints, previously published stories that had appeared elsewhere. I’d written a horror story called “Blood in the River” that had appeared in Dead Bait, published by Severed Press. As written, it was unsuitable for Re-Terrify, so I revised it.

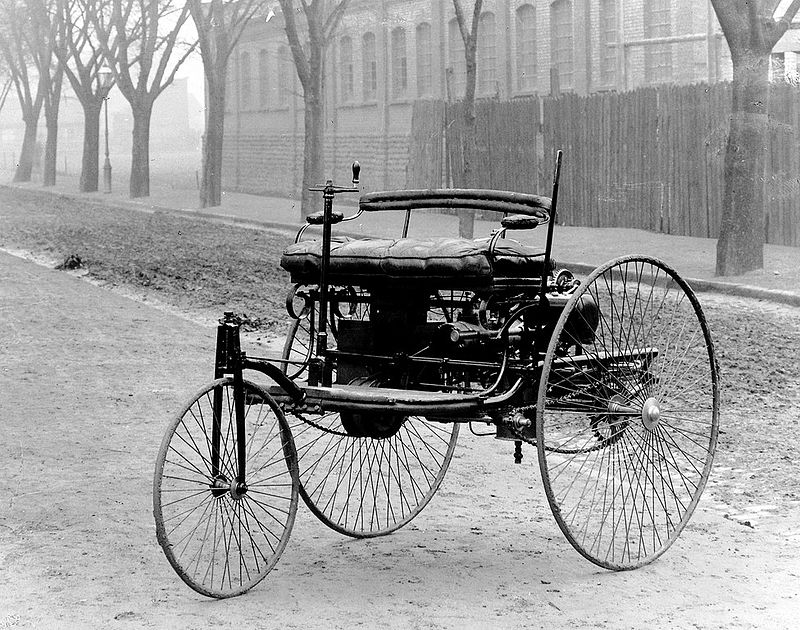

In the story, detectives at an El Paso police department are questioning a murder suspect. The suspect claims to be about four hundred years old and to exist as a kind of vampire. At moonset, he turns into a vampirefish, a candiru. At moonrise, he turns back into a human male. In either state, he is invincible. Once it becomes clear he is telling the truth, the police are faced with the problem of defeating an invulnerable monster.

That much remains the same in both versions of the story. How did I revise it? Aside from changing the title, I changed the protagonist from male to female, fleshed out her role at the police department, heightened the tension, deleted a couple of scenes, and added a more dramatic final scene.

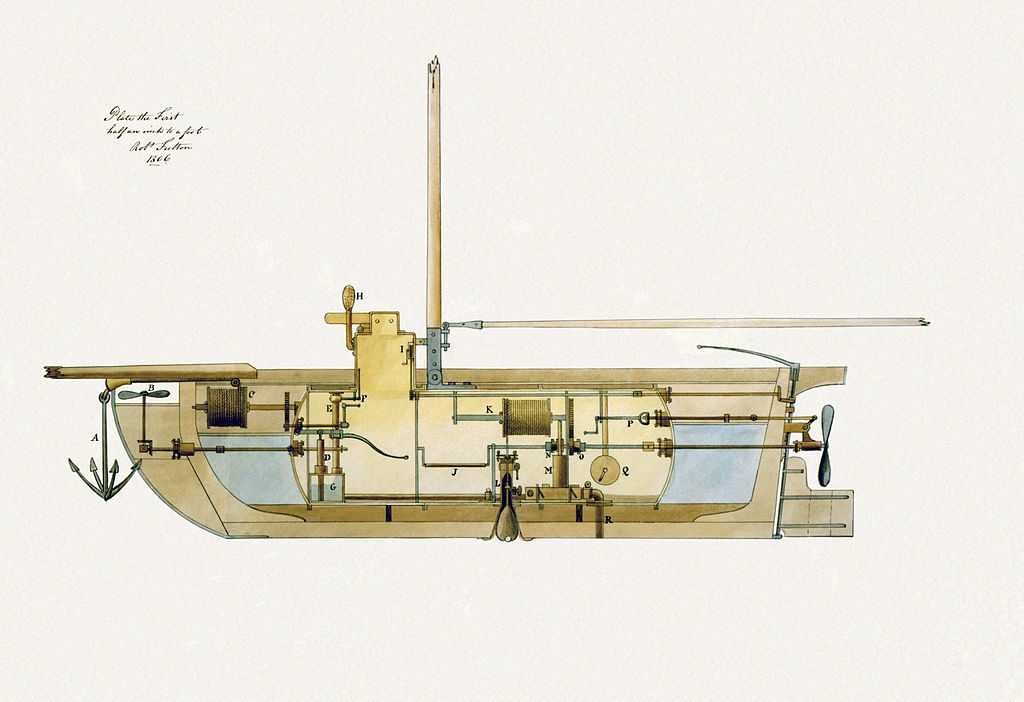

The real-life candiru is scary enough. It wedges its barbed head into the gills of larger fish and sucks their blood until gorged. The antagonist of my story has that hideous capability in both his forms. In his human shape, he can spring blood-draining barbs from his fingers, and from a lower body part.

Neither bullets nor fist blows affect this villain. Nor do the traditional wards used against vampires. In both his forms, this shape-shifter is invulnerable to any attack.

What is my hero, Kendra Monroe, to do? How do you fight an unbeatable foe?

To find out, you’ll have to buy Re-Terrify and read “Moonset.” I look forward to reading the other stories in this anthology, too. In the meantime, that song from Man of La Mancha is now stuck in my head, and I have nobody to blame except—

Poseidon’s Scribe

Author Anne R. Allen wrote an

Author Anne R. Allen wrote an