Stay in your homes, the experts tell us. Keep away from others. Don’t gather in bars, restaurants, or theaters. There aren’t any sports. All your club meetings are cancelled. The boss called off that business trip and made you telework. You’re bored, being at home all the time. You’ve gone stir-crazy. What to do?

Here’s my answer—write something.

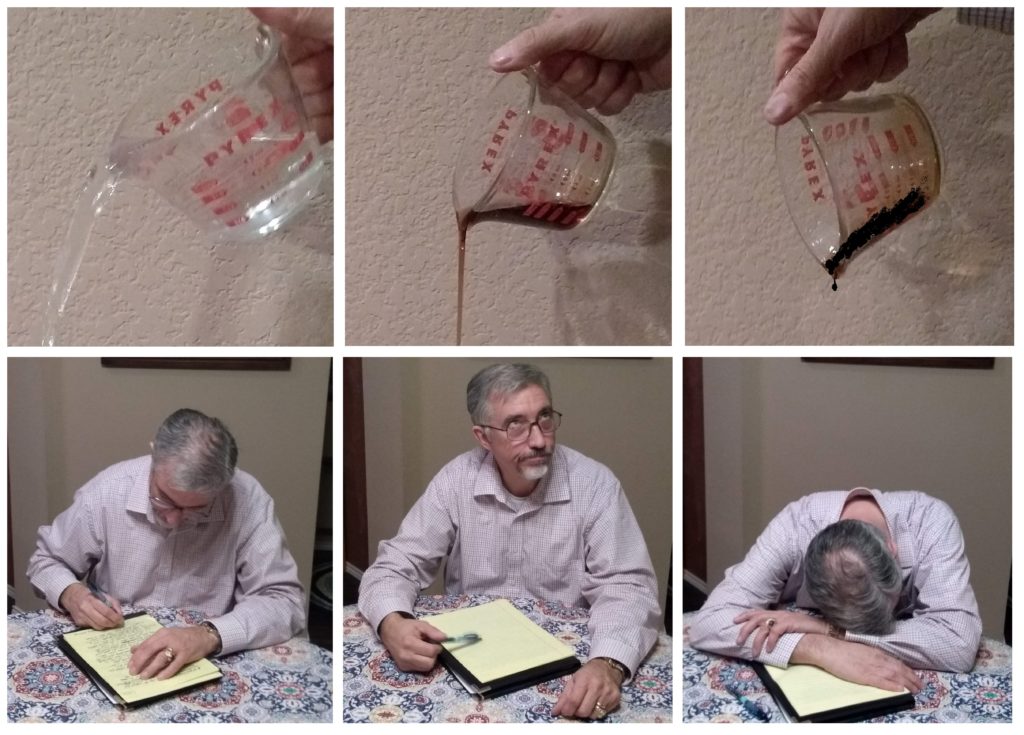

That’s right. Sit at your keyboard, or grab pen and paper, and write something.

“But,” you’re saying, “I’m not a writer!”

My answer—how do you know?

Here’s my list of stir-craziness cures, staring with the easiest ideas:

- Why not make a list of supplies you’re going to need soon? Wow! You’re writing!

- Remember that personal organizer book you bought back in 2015, and never used? Dig it out. You could come up with some life goals, and plans to achieve them. Maybe even a personal mission statement. Or a bucket list. You never found time for that before, but you’ve got time now.

- Start a journal (or diary, or logbook—call it what you want). Write down whatever occurs to you. Write about social distancing, and how much you hate it. Write about feeling like you’re under house arrest, the isolation and loneliness. Get the emotions out. Write as if nobody will ever read it.

- Write emails to relatives and friends you haven’t connected to in a while. Write tweets and Facebook posts. Write old-fashioned letters, on stationery; the Post Office still delivers.

- Write an article, essay, or vignette. The topic should be something you know about. At first, write as if you’re not going to send it anywhere. Later, as you look back over it and fix it up, it might not seem half bad. Perhaps it’s publishable.

- Start a blog. You can do it. It probably won’t change the world, but it might help you, and that’s a beginning.

- If you’re up for fiction, start with something short. There’s the six-word story, the 280-character story (twitterature), the dribble (50 words), the drabble (100 words), sudden fiction (750 words), or flash fiction (1000 words). Editors are looking for good stories of these lengths, and readers like them too.

- How about poetry? Can you make words sing, or fly, or lift a heart?

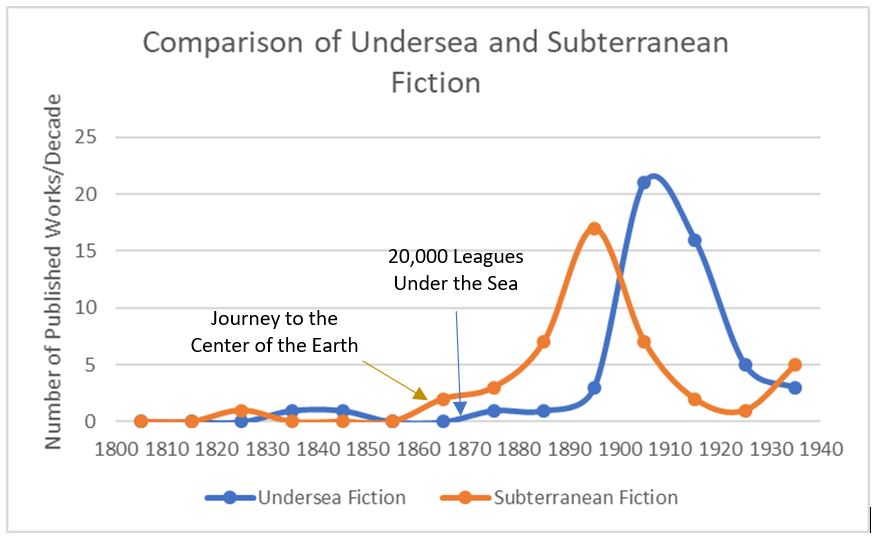

- Create a short story, with a few characters, or even just one. Focus on a single effect or mood. Editors and readers love well-written short stories. In fact, I know two editors searching for 3000-5000-word short stories inspired by Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. Read the rules here, write your story, and send it in!

- Write a non-fiction book. You’re an expert in something. Perhaps you can expand that essay you wrote (see #5 above) to book length. Cookbooks, history books, coffee-table books, memoirs—they get bought all the time. Ooh, how about a travel book? Few people are traveling now, but everyone longs to.

- Write a children’s book, or YA (young adult). You’ll need a good imagination and the experience of having been young.

- Write the Great American Novel. As they say, writing a novel is a one-day event (as in ‘One day, I’ll write a novel’). You’ve got time now; excuses are gone. No need to wait for November; you can have a personal Nanowrimo now.

You may be cooped up, but your imagination isn’t, your words aren’t. Set them free! There’s no charge for this prescription for stir-craziness written by—

Poseidon’s Scribe