You’ve been hearing the term ‘Clean Fiction’ and wondering what it means. That questioning mind of yours shall soon be satisfied. Or, perhaps, left even more confused.

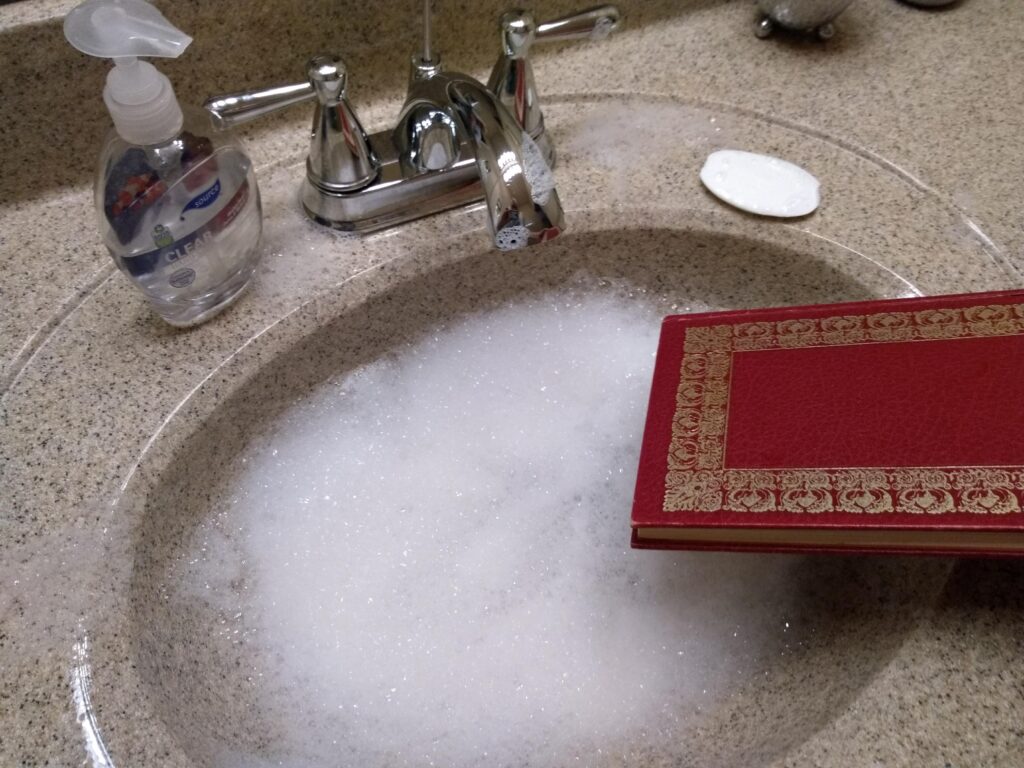

Apparently, ‘Clean Fiction’ doesn’t require you to physically wash a book in soapy water. My bad.

The clearest definition of the term is: fiction both young adults and mature adults can enjoy.

In these pandemic times, with parents spending more time at home with children, sometimes home-schooling them, there’s a hunger for such stories. For that reason, the Story Quest Academy has been championing the cause of clean fiction.

From a writer’s point of view, how do you write a clean story? How does such a story differ from an unclean one?

I recall reading where Robert Heinlein said writing for young adults (called ‘juveniles’ in his day) was the same as writing for adults, you just take out the sex and swearing. The dozen ‘juvenile’ novels he wrote, though dated, remain readable and exciting today.

He warned writers against talking down to teenagers. If you think they aren’t ready for deep themes, long words, mild violence, or literary symbolism, you’re underestimating them.

These days, you could even leave in some mild swear words. Today’s YA audience has heard them.

Author Allison Tebo makes some interesting points about clean fiction in this post. Writing clean fiction, she says, forces you to be a better writer. You can’t fall back on sex or swearing to hold the reader’s interest. The action, dialogue, and word choices in your story must step up to do that.

Moreover, Tebo states that clean fiction is more likely to become classic fiction than typical adult-only fiction is. By appealing to nearly all age groups, a clean story become more universal and welcoming. If it is good enough, it may well become a classic, enjoyed for generations, even centuries.

Like Tebo, I grew up reading and loving clean fiction. Nearly all the science fiction I read was clean. In fact, teenagers were perhaps the main intended audience for that genre.

My own fiction tends toward the clean side. Exceptions include my horror story, published as “Blood in the River” and later, with alterations, as “Moonset.” Ripper’s Ring contains violence teens might find upsetting, though it’s not graphic.

If you go looking for my stories, many appear in anthologies along with tales written by other authors. In general, those stories, too, are clean, with the exception of those in the horror anthology Dead Bait.

I guess you could say I’ve been writing clean fiction before it was a thing. Creating stories so clean you could wash your hands with them, I’m—

Poseidon’s Scribe

I’ve seen this term.

On the one hand, I’ve been teaching long enough to know how uncomfortable it is when something “unclean” comes up in reading material or a video used in class. And I’d be lying if I didn’t say that as I put together material of my own, I try to avoid images and subjects that may make teachers squirm in front of students.

On the other hand, therein lies the problem, I think. Adults are deciding what’s clean depending on what may make them feel uncomfortable discussing around young people, not on what young people can and cannot mentally and emotionally handle. And ultimately, anyone who was ever been young realizes that teens are going to find the “unclean” material no matter how hard adults try to keep it from them. Sanitization simply pushes the “filth” underground.

There’s also the danger of becoming germaphobes, seeing dirt everywhere in fiction. Ten years from now, will Harry Potter be clean or unclean? “A Wrinkle in Time”, “Are You there God? It’s Me, Margaret”, “The Chocolate War”, weren’t considered clean in their time, and even now I can imagine adults finding serious issues with them again one day. Their core messages are quite subversive.

Thanks for the comments, Todd. Yes, many teens can deal with topics that adults don’t think they’re ready for, or don’t want them to be ready for. The artificial 18-year dividing line between child and adult is both too abrupt and unrealistic.

And the matter of changing mores is always a problem. It seems especially so today, when social media can declare something passe/out/gone/cancelled on a crowd-induced whim. The old performer’s half-joking lament was, “Everyone’s a critic,” and that’s become literally true these days. Everyone’s a vocal critic with a worldwide voice. What once was clean can become unclean in a seeming instant, and vice versa.