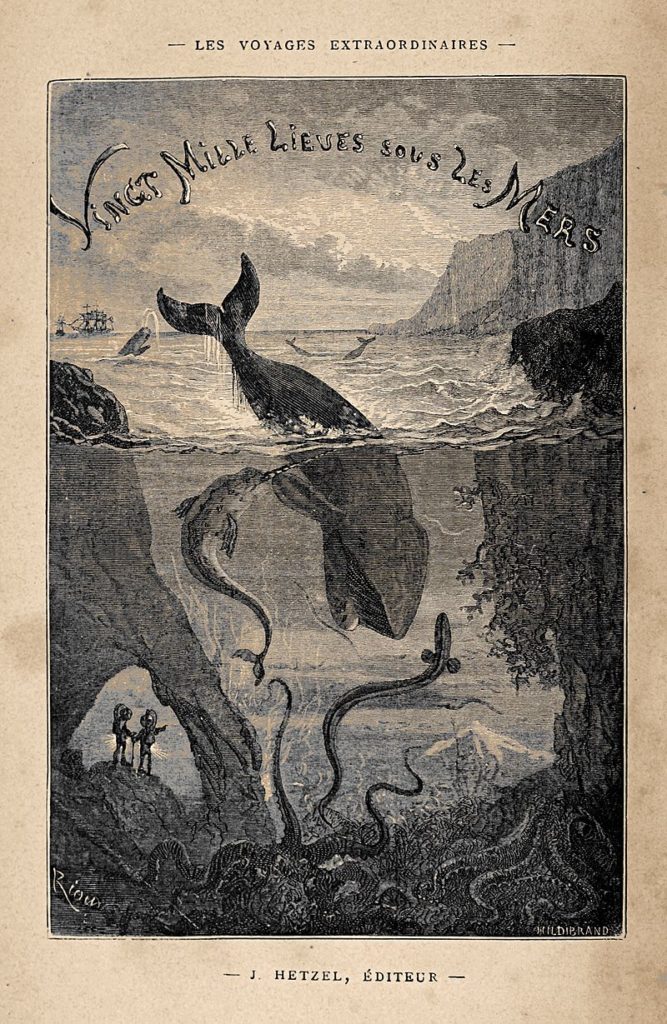

The publication of Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea led to a boom in books about undersea adventures. But the boom didn’t occur immediately and Verne wasn’t the sole cause.

Before explaining all that, I’ll mention an upcoming anthology of short stories titled 20,000 Leagues Remembered, scheduled for release on the 150th anniversary of Verne’s submarine novel. Until April 30, fellow editor Kelly A. Harmon and I are accepting short stories inspired by that novel. For more details and to submit your story, click here or on the cover image.

Verne wasn’t the first to venture into undersea fiction, though the predecessor works are fantasy, not science fiction. The list is brief. If I stretch the definition of undersea fiction, it includes the Biblical story of Jonah, Edgar Allan Poe’s 1831 poem “The City in the Sea,” and Theophile Gautier’s 1848 novel Les Deux Etoiles (The Two Stars). At least the latter included a submarine.

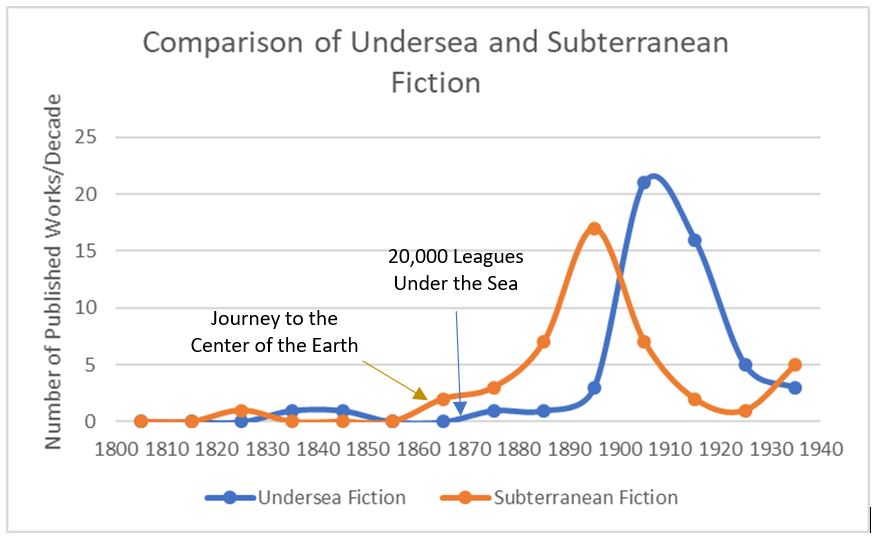

As shown by the graph, many books involving submarines appeared in the years following Verne’s undersea novel. The vast majority of these were intended for what we now call the Young Adult market, and included works by Harry Collingwood, Roy Rockwood, Luis Senarens, Victor G. Durham, Stanley R. Matthews, and Victor Appleton.

In a similar manner, Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864) preceded an explosion of novels with subterranean settings. To a lesser extent, these also included many YA works.

But notice a curious thing about the two curves. The rise in subterranean fiction occurs earlier and starts its upward trend earlier than does the curve for undersea fiction.

I have three theories to explain this.

- The most obvious reason is that Journey to the Center was published six years before Twenty Thousand Leagues. That six-year gap doesn’t explain it all, however.

- I believe other authors, after reading Twenty Thousand Leagues, were daunted by the prospect of imitating that novel. To write credibly about submarines required knowledge most writers lacked. However, subterranean fiction required no geological expertise and no vehicle. Moreover, the writer’s underground setting could include any fantasy elements imaginable.

- I think the later peak in submarine novels had less to do with Verne than it did with the introduction of real submarines into the world’s navies. With actual submarines becoming familiar to readers, authors could pattern their fictional vehicles after real ones.

Neither of these mountain-shaped curves is due solely to Verne’s works. They both coincide with a boom in publishing adventure fiction of all kinds, not just undersea and subterranean. A drop in publishing costs, a rise in disposable income, a recognition that young people craved to read—all these factors attracted writers and publishers to new opportunities.

Still, I don’t want to understate Verne’s impact on undersea fiction either. Prior to Twenty Thousand Leagues, such works were fantasies. Afterward, they were either science fiction or real-life adventure stories.

After the publication of Twenty Thousand Leagues, it became the standard to which later submarine novels got compared. Even today, 150 years later, if you ask people to name a submarine novel, most likely they will either answer with The Hunt for Red October, or Verne’s book.

I just can’t help this fascination with stories of the sea. After all, I’m—

Poseidon’s Scribe

It’s a fascinating machine, advanced well beyond what anyone gave the ancient Greeks credit for. Moreover, until x-ray tomography was conducted on the device in recent years, no one knew what it was for.

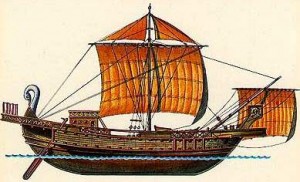

It’s a fascinating machine, advanced well beyond what anyone gave the ancient Greeks credit for. Moreover, until x-ray tomography was conducted on the device in recent years, no one knew what it was for. When research revealed the wreck to be a Roman merchant ship, I checked out what those ships were like. They differ from trireme warships in interesting ways. The carved neck and head of a swan which I describe in the story was actually a common feature of these ships.

When research revealed the wreck to be a Roman merchant ship, I checked out what those ships were like. They differ from trireme warships in interesting ways. The carved neck and head of a swan which I describe in the story was actually a common feature of these ships.