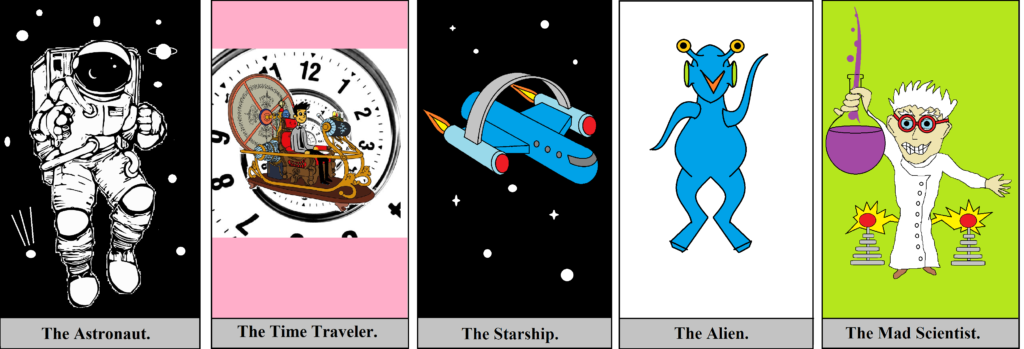

I know, I know, when I used a crystal ball two years ago, my predictions didn’t pan out. Then when I read tea leaves last year, my prognostications were in error. But you can believe me this year. I’m using SciFi tarot cards to predict what will happen in 2021.

The cards can’t possibly be wrong. Here are my predictions for science fiction books in the year 2021:

- Disease Stories. Inspired by the COVID-19 virus, there will be stories of even deadlier diseases, perhaps intelligent diseases. I see stories of pandemics, extreme isolation, and how characters deal with mass death.

- Rebirth. I foresee stories of characters getting back to normal after pandemics, stories about the rebirth of society.

- Private Space Exploration. Inspired by Space-X, stories of space travel will involve companies, not governments.

- Humor. There will be a surge in funny scifi, mainly because we can all use it right now.

- Artificial Intelligence. Writers in 2021 will continue to explore this topic as they have for decades, but with greater urgency as computer scientists get closer and closer to developing Artificial General Intelligence, and perhaps Artificial Super Intelligence.

- Anti-Capitalism. I predict there will be stories pointing out, in fictional form, the deficiencies of capitalism. Anti-capitalist themes may only form the backdrop of the story, but they will be there.

- China. In 2021, I see an uptick in scifi books involving China in some way. Some will be written by Chinese authors, and some stories will be set in China.

- Fewer Aliens. Alien tales are out in 2021. Of the few that will be published, they will involve communication only, not visitations, let alone abductions or invasions.

- Urban Scifi. Paralleling the urban fantasy subgenre, we’ll see a lot of scifi books in 2021 that start out in a modern-day city setting, and go from there.

Personal Predictions

Here are three other prophesies for 2021, but these involve me in some way:

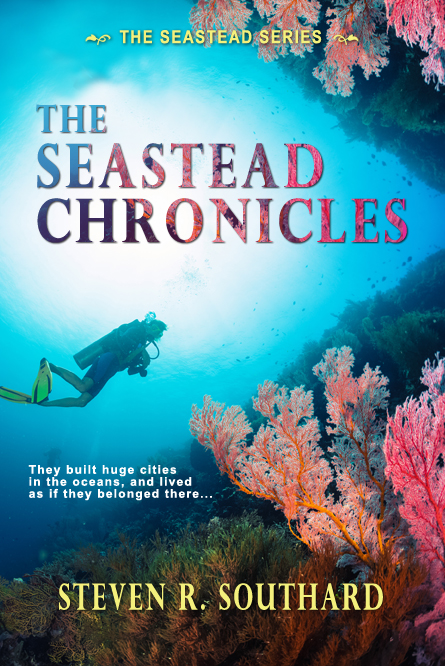

- The Seastead Chronicles, my collection of short stories about the future history of seasteading, will be published in 2021.

- The North American Jules Verne Society will publish its first anthology of short stories, (working title: Extraordinary Visions: Stories Inspired by Jules Verne) all inspired by Jules Verne, in 2021, and I’ll be on the editorial team. You can write a story for it. Click here for details.

- Pole to Pole Publishing will put out an anthology of reprinted military science fiction short stories in 2021, titled Re-Enlist. I’ll serve as co-editor of this one. Stay tuned to this blog for more details.

In late December of 2021, I’ll post my assessment of the above predictions, and you’ll see there’s no better reader of tarot cards than—

Poseidon’s Scribe