Oh, English. You’re an interesting language, but you’re burdened with some old baggage. Maybe it’s time you changed.

Today is International Pronouns Day (IPD). A day to recognize your acquaintances might choose different pronouns than you expect, and it’s only polite to use the ones they want.

You might meet a stranger who says, “Hi. I’m Jessica and I go by the pronouns ‘he’ and ‘him.’ Since Jessica told you that, it would be impolite if you said to someone else, “I just met Jessica, and she…”

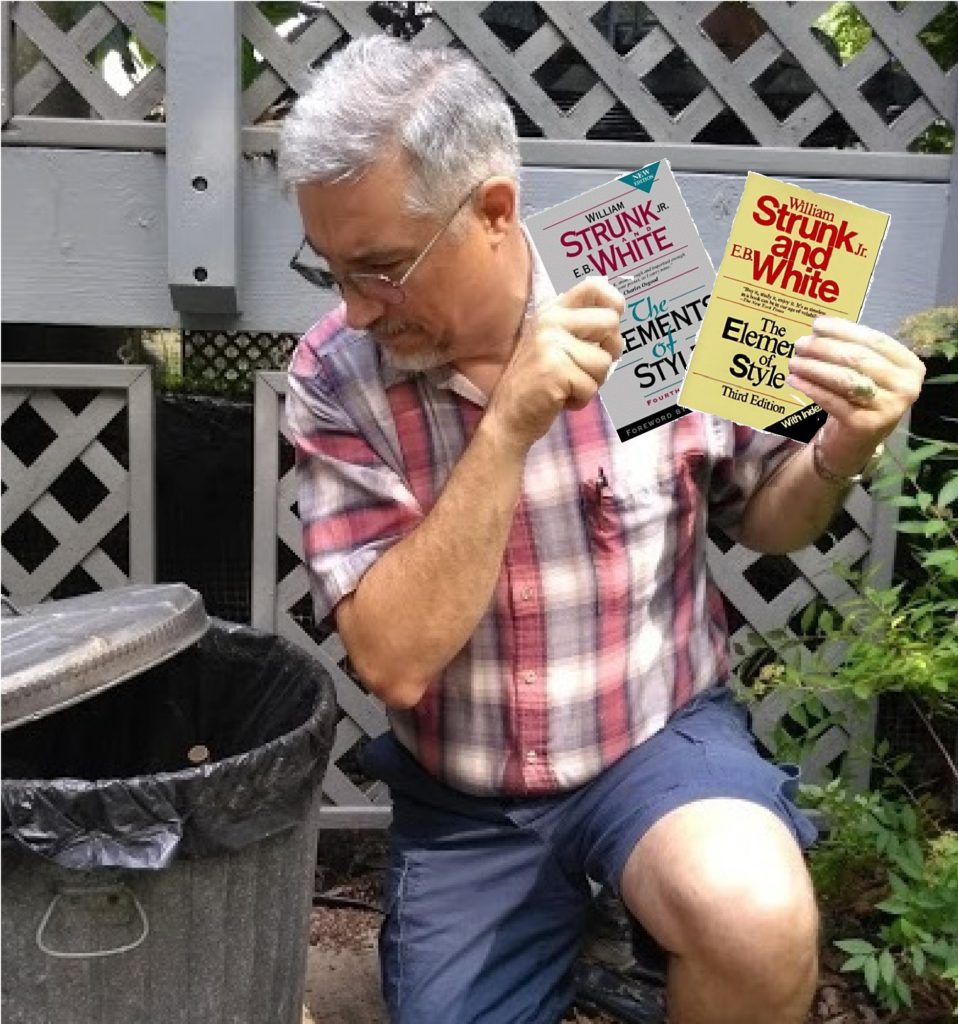

The discussion of pronouns interests me as a writer. As English changes, I’d like to keep up with it.

In general, pronouns serve as a naming shorthand, enabling us to refer to a person repeatedly without stating the person’s name each time. In a traditional written story, when a female character is speaking with a male character, the author need only write ‘she said’ or ‘he said’ and the reader can follow the dialogue with ease.

Although English does not divide all nouns into feminine and masculine genders as some other languages do, present-day English does include gender-specific pronouns such as ‘she,’ ‘her,’ ‘he,’ and ‘him.’ Although many people seem happy with that arrangement, some prefer to be thought of as an individual, not as a member of one or the other gender.

At the moment, the English language hasn’t settled on an agreed set of non-gender-specific pronouns for people. ‘It,’ ‘Its,’ and ‘Itself’ seem too dehumanizing. While many candidate pronouns vie for the honor, that leaves us in a period of flux until winners emerge through widespread use.

In the meantime, you may choose your own preferred pronoun, and—according to the promoters of International Pronouns Day—inform your friends and new acquaintances. They, in turn, should respect your wishes.

Still, I find it difficult to change at my age. I grew up in a time when you couldn’t choose your own pronouns. Language and biology chose them for you. I now have enough problems remembering people’s names, and if all my acquaintances chose different pronouns, I’d go around mis-pronouning them all the time.

In my fiction, I stand a chance of abiding by the IPD guidance. I just finished reading a novel where characters introduced themselves by stating their name and preferred pronouns. For my stories set in the world of today or the near future, I could do the same thing. Depending on how appropriate it might be for a given character, I’ll try it.

In the meantime, I wish you a happy International Pronouns Day. Delighted to meet you. I’m—

Poseidon’s Scribe (he/him)