Your personality type determines how you write and what you write. Sorry, but that’s a proven scientific fact (says the guy who’s not an expert on personalities, science, or writing for that matter).

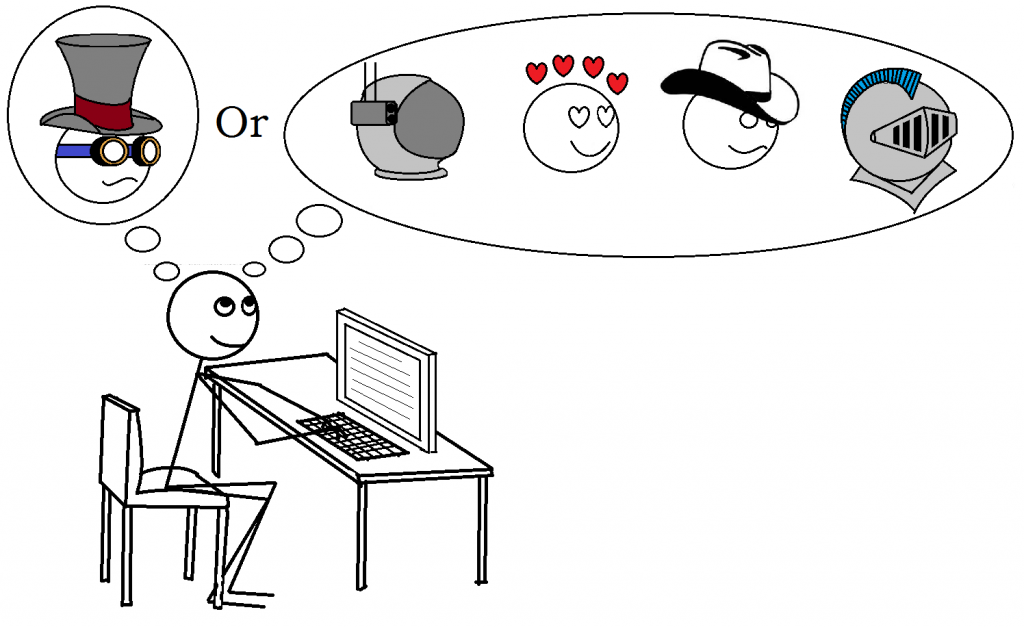

In last week’s post, I cited Lauren Sapala’s claim that two Myers-Briggs personality types seemed most suited to pantsing (writing without an outline), rather than plotting. That got me wondering—does your Myers-Briggs Type Indicator reveal your writing process, and the genre of your fiction?

Kate Scott explored this topic well and I recommend her post. What follows is my whimsical take. To determine your type, take this online quiz. Then skip to my assessment of your type. If my write-up doesn’t ring true, well, I warned you. If you do identify with what I wrote, that proves even a blind pig, etc.

ENFJ

Process—Lucky you keep a notebook of interesting words and phrases. Now post that calendar with the deadline circled, and get ready to educate the world. If you can’t collaborate with a co-author, then at least consult.

Genre—Young Adult, with realistic teenage dialogue

ENFP

Process—Time to brainstorm with fellow writers. Get the feel of each character—know them like family. Let those metaphors and similes flow.

Genre—literary fiction or highbrow romance, where you connect your characters to the big ideas, the eternal aspects of human nature

ENTJ

Process—You joined a writer’s group, and soon became its president. You’ve researched all aspects of your book and could teach a college-level course in each. You’ve posted a mind-map on the wall near the executive chair in your ‘command bunker.’ All that remains is to adhere to your detailed outline.

Genre—technothrillers bristling with advanced gadgets, accurate in every detail

ENTP

Process—Peruse your ‘ideas file,’ now bulging with dozens, even hundreds, of story ideas. Bounce notions off your online fan club, or sit with friends at the coffee shop to discuss the book. Follow the intricate plan you’ve laid out.

Genre—mysteries featuring a clever detective, or other problem-solving stories where your hero contrives an ingenious solution to a bedeviling dilemma.

ESFJ

Process—you take your voice recorder everywhere, ‘writing’ by talking first. Collaboration? Heck, you tell everyone about your book, from the grocery clerk to your co-workers. Outlines bore you, so you write on the fly.

Genre—any popular genre, since you know what readers want, but always in first-person, like you’re telling a campfire story

ESFP

Process—You host a party, and the main entertainment is a freeform brainstorm of your story. A few drinks liven things up. For the actual writing, if you’re not collaborating with one or more co-authors on the effort, you wish you were.

Genre—romance, featuring your clever wordplay. with a huge cast of characters, often attending parties

ESTJ

Process—Somebody’s put out a submission call you like, so it’s time to sit at your well-ordered desk and craft an outline. Soon a theme emerges as you work to achieve each milestone of your plan.

Genre—short stories in any genre, prompted by submission calls, written in clear prose, about characters using logic to resolve conflict

ESTP

Process—Good thing you’ve assembled your collection of note cards with all the facts you’ll need. Now head to your favorite restaurant with your writer friends. Once the outline’s done, get the story written and published, because the real fun is at the book signings.

Genre—any genre where your characters can talk their way out of difficult jams

INFJ

Process—You’ve been people-watching in the park, notebook in hand, so you’ve now formed an image of your characters. You even know which actors should play them in the (please let it be!) movie. No outline will constrain you as you let the characters take the story where they will.

Genre—Romance, of course

INFP

Process—Home now after your daily nature walk, you retire to your writing niche, energized by fragrant incense and stimulated by seeing your favorite decorations. Time to write, unhindered by outlines or any assigned topics, you write what you want. You’re no sell-out to the market.

Genre—literary fiction of a deep, introspective, and moody nature

INTJ

Process—You’ve never shown anyone where you write, and you call it your ‘secret lair.’ A blueprint of your story fills the screen of one of the monitors on your desk. Maybe that first draft didn’t work, but that’s why you edit.

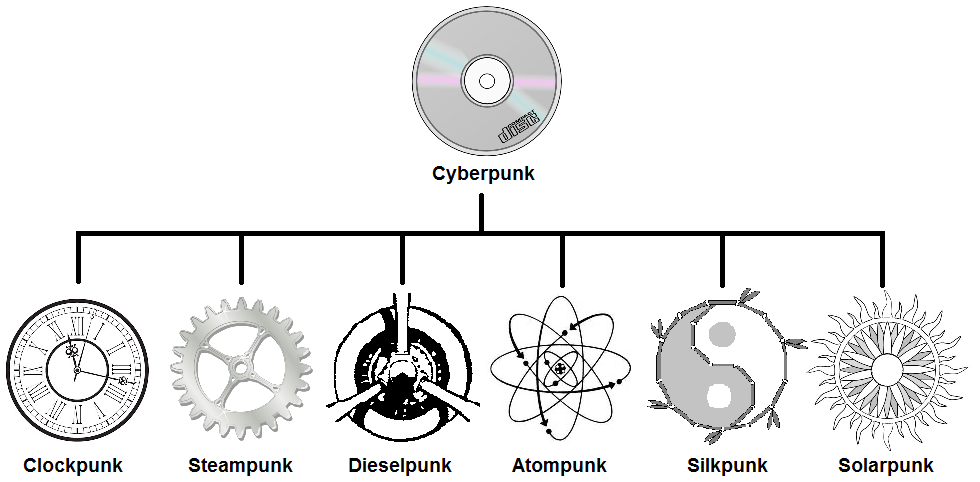

Genre—science fiction, alternate history, or steampunk, but always containing political overtones

INTP

Process—It’s well past midnight, but you don’t care, or even notice. You’re writing what you like. The detailed outline guides you. Thanks to careful research, and your collection of how-to-write books, you’ve learned a lot, and that’s the point.

Genre—mixed-genre novels, the kind booksellers can’t categorize, as well as experimental novels that explore untried plot structures

ISFJ

Process—You’ve done your research and know the plot types and tropes that work for readers. You’ve carved out this time to work without interruption, after first ensuring others in your home don’t need you for anything.

Genre—Historical fiction, in your easy style, all parts in harmony, designed to entertain and educate

ISFP

Process—You’re outdoors, on your deck or patio, or in the park, music playing in your earbuds. In your mind, you picture a reader enjoying your book. You just returned from a trip to the city of your novel’s setting, where you soaked in the ambiance of the place. That brisk walk you took earlier sure stimulated your muse and collected your thoughts about the submission call you’ve chosen to respond to.

Genre—novel-in-verse or literary fiction

ISTJ

Process—Here in your home library, surrounded by reference books (including a well-thumbed thesaurus), outline, schedule, and spreadsheets, you’re set to go. You’ve also hand-built a model of the very thing you’re writing about, to inspire you.

Genre—mysteries with a clever detective

ISTP

Process—Above your desk, you’ve posted a clear, one-sentence goal for your book. Nobody tasked you to write this book, and nobody else could craft it as well. You’re going to work as long and as hard as it takes to meet your high standards. Nothing but the Great American Novel will do.

Genre—any established genre, and you aim for the top spot in it

Eerie, isn’t it, how I knew your writing process and genre from your Myers-Briggs personality type alone? What can I say? It’s a super-power reserved to, (and used only for good by)—

Poseidon’s Scribe

You might have rejected the idea of switching genres already. I can hear your reasons now:

You might have rejected the idea of switching genres already. I can hear your reasons now: