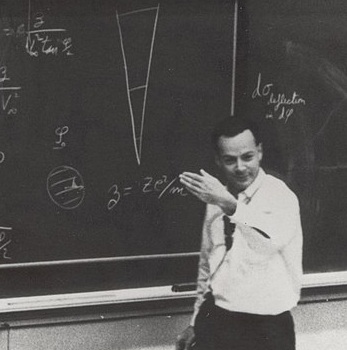

You science fiction writers and technical writers face a difficult problem. How do you convey complicated information to an average reader in an understandable way? The late Dr. Richard Feynman may have your answer.

Who Was Richard Feynman?

Feynman (1918-1988) studied quantum mechanics, helped develop the atomic bomb, foresaw nanotechnology, investigated the Space Shuttle Challenger accident, and won a Nobel Prize in Physics. For purposes of this blogpost, Dr. Feynman developed his own technique for learning and understanding things.

The Feynman Technique

Wikipedia mentions the technique here. In brief, here’s how to do it:

- Research your topic

- Teach it to a child

- Fill in knowledge gaps

- Review, organize, simplify, and go back to step 2.

First, find out as much as you can about the subject. The second step requires you to teach it to a child who’s about eight years old. You can simulate that step if you wish, but it forces you to use simple words and think of relatable analogies. While doing this, you’ll notice holes in your knowledge (often by confusing the eight-year-old), so the next step involves seeking source materials to fill those gaps. Then you can review your notes, put them in order, simplify them further and try again to teach the topic to a child.

Thoughts on the Technique

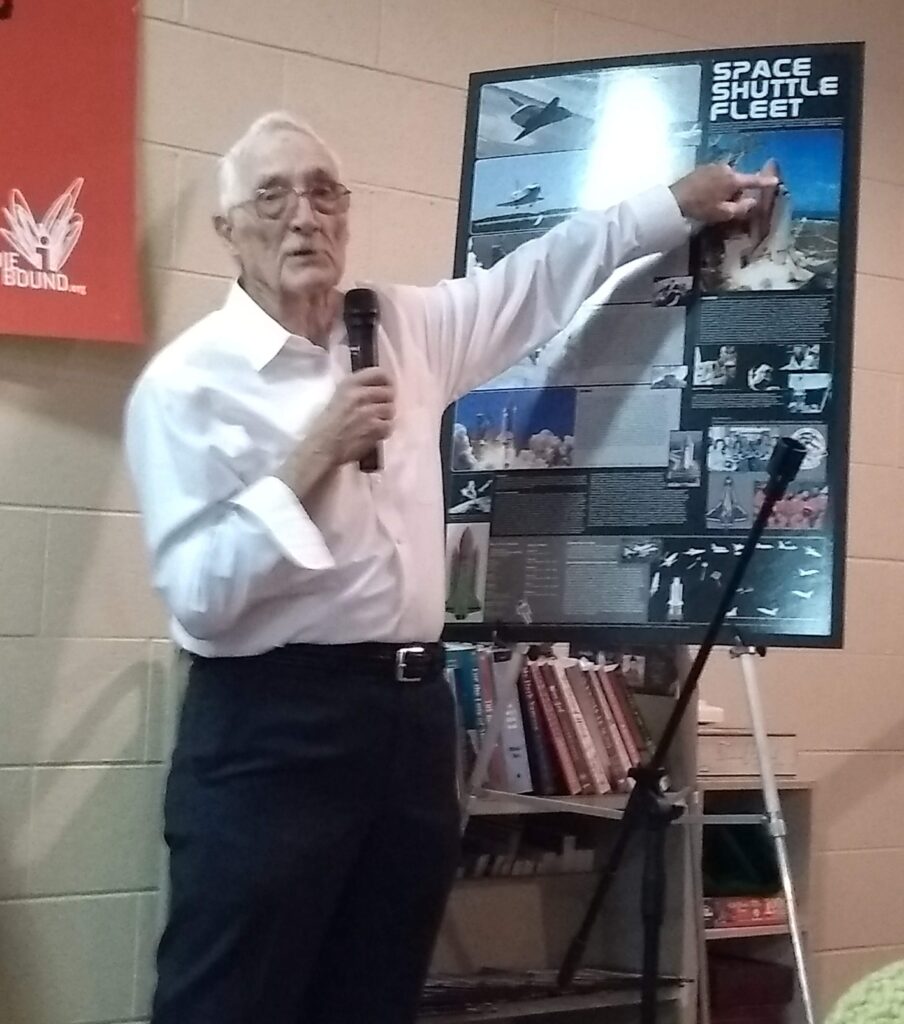

My father used to participate in historical portrayals, in which he acted the part of a historical figure. One time, he chose Richard Feynman, not so much for the scientist’s learning technique, but for his space shuttle commission work. Still, in preparing for his presentations, my dad made use of the technique to get to the essence of Feynman himself.

I wish someone had shown me the technique when I was going through school. Even if I’d imagined I’d have to teach the topic to others, I would’ve paid more attention.

How well do we know what we know? Could we teach an eight-year-old a complex subject? While in the submarine service, I had to study all the systems on the boat. Qualified watchstanders asked me detailed questions about each system, probing until they reached something I didn’t know. Then they’d send me away to look up the answer to the missed questions. That process shares similarities with the Feynman Technique.

Later, in my engineering career, I came upon other engineers who used big words, but I suspected they only knew how to pronounce them, not the details of their meaning. Some people try to impress with high-sounding language, but often those who use simpler vocabulary understand subjects best.

How Can Writers Use the Technique?

Author Isaac Asimov explained complex topics in plain terms. Few writers demonstrate that skill. More than other fiction genres, science fiction delves into complicated technical subjects. Writers strive to entertain, not educate, so must work their explanations into the prose in a manner that neither confuses readers nor slows down the action.

Following the Feynman Technique can help with that. If you follow that method, you’ll know the material well, and possess the simple words and analogies to allow you to convey it to readers without info dumps or head-scratching jargon.

If you need to understand a new topic, or describe it to readers, try the Feynman Technique. It’s a new favorite of—

Poseidon’s Scribe