You’re a fiction writer who wants to crank out better books faster. Maybe this blogpost will help you do that.

Intro to Uptime

I just read Uptime: A Practical Guide to Personal Productivity and Wellbeing by Laura Mae Martin. The author worked as a productivity expert at Google who helped employees do more work faster, with less stress. Could her techniques work for fiction writers?

She packed her short book with numerous techniques, and many might work for you. I’ll focus on one of those here.

Power Hours and Flow

She discussed the concept of ‘power hours,’ the few hours of highest productivity in your day. That sounded a bit like being ‘in the flow’ to me. I’ve blogged about that wonderful feeling before. Picture the flow state as focused concentration, effortless action, a lack of self-consciousness, unawareness of time, and obliviousness toward bodily needs.

When I wrote about it, I imagined doing the more creative phases of writing while in this flow state. But fiction writing includes more than creativity and that complicates the picture.

Off-Peak Hours

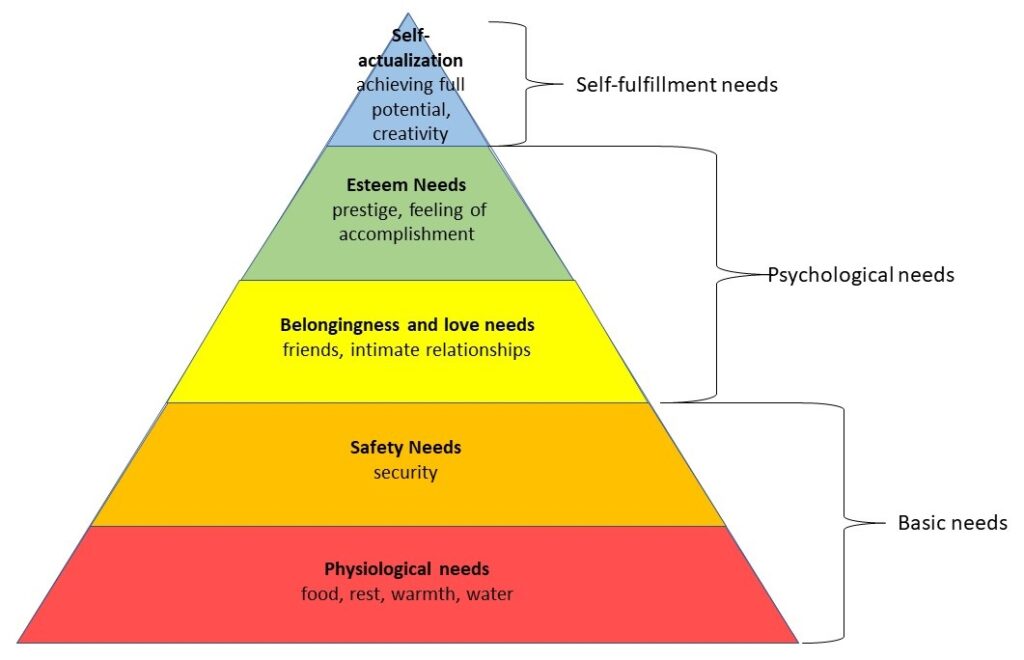

In addition to power hours, Martin discussed off-peak hours, during which fatigue sets in (or continues from the night) and you’re less productive. Each of your workdays contains power hours and off-peak hours, and they’re somewhat stable, occurring at the same times each day. However, these cycles vary between people, so you’ll have to experiment to discover your own power hours, if you haven’t already identified them from past experience.

Uptime, Downtime

Uptime, if I understand her concept, can include both power hours and off-peak hours. During uptime, you’re performing work, but not always at the same level of productivity.

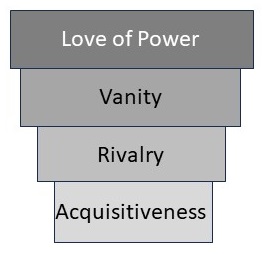

However, for your health, you require downtime, too. Downtime includes non-work-related activities, particularly those requiring little concentration. Examples include meditating, showering, walking, mowing the lawn, gardening, etc. Unlike power hours and off-peak hours, you can schedule downtime. You’re in control.

Funny thing about downtime. People report their most creative ideas occur then. Fiction writers can use that to their advantage.

Fiction Writing Tasks

The fiction writing process contains many tasks, including generating ideas/brainstorming, outlining/researching, writing the first draft, editing later drafts, and marketing. Some require more creativity, some less.

If you had the option, you’d choose to accomplish your highest priority writing tasks during the power hours—in the flow, ideally. You’d save routine or less vital tasks for off-peak hours.

Don’t forget the advantage of downtime, which you control. Say you get stuck while writing—a plot problem, a character motivation issue, etc. Take some downtime, a few minutes off from writing. Your subconscious may work on the problem and solve it when you least expect it.

Get Real

I know—most fiction writers have day jobs. You seize as much writing time as you can, cramming it in among all the other obligations of life. Some days you barely write for half an hour. Perhaps your writing time varies from day to day. How are you supposed to make use of this uptime/downtime/power hours/off-peak hours concept?

Maybe you can’t. But perhaps just being aware of your daily productivity cycles and the creativity-laden power of downtime will help you reschedule as close to your optimum writing times as you can. Also, this knowledge may help you squeeze the most from those rare days you can devote to writing.

Uptime over. It’s now downtime for—

Poseidon’s Scribe