It’s tough enough to lay out the plot for a book. Now I’m supposed to have a plot for each scene? Seriously?

Yeah, seriously. This past week I watched on online Zoom presentation by author John Claude Bemis. He called the technique ‘microplotting.’ I’ll introduce it here, in my own words. Any differences between what he meant and what I wrote are my errors, not his.

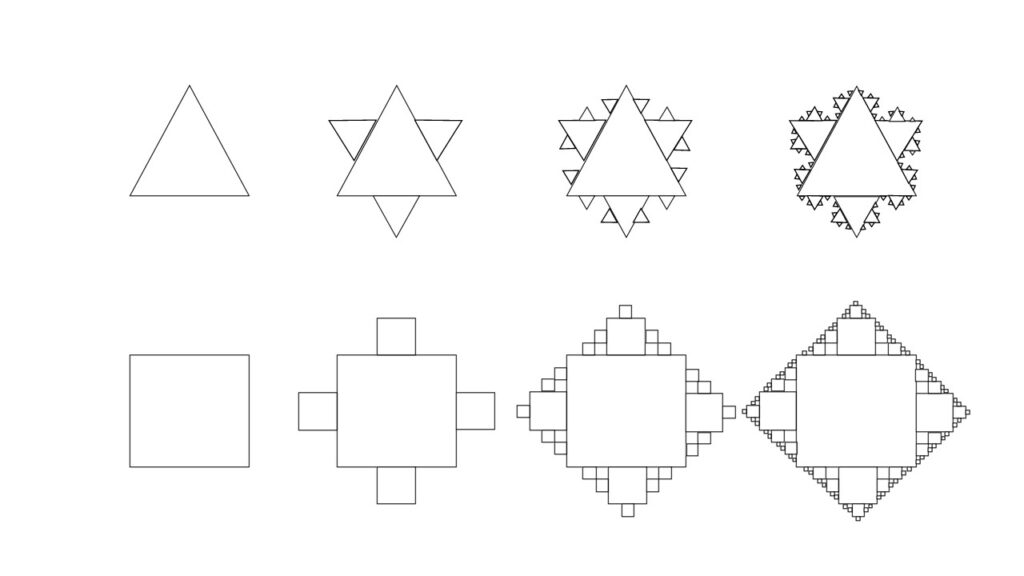

First, why does each scene of your book need a plot, if the overall book already has one? Bemis says it’s because there won’t be enough truly dramatic moments in your book to hold a reader’s interest. You need something in between those moments to keep your audience engaged.

What’s that something? Smaller dramas along the way. A plot for each scene. These small plots may lack the overall intensity or import of your book’s overall plot, but they should contain elements of anticipation, tension, and expectation to keep readers eager for more.

According to Bemis, each scene should either advance your overall plot or deepen the reader’s understanding of a character, or—better—both. He suggests putting yourself in the mind of the reader. Your scene should introduce a question in the reader’s mind. Before answering that one, introduce another question to keep the anticipation going. Don’t forget to answer each question, though, to resolve the tensions you’ve created.

Bemis provides five questions to ask yourself as you start to structure a scene:

- What does the character want? Maybe to reach a location, to obtain something, to answer a question, or to persuade someone.

- Why can’t the character get what she wants? Some obstacle, some friction with another person, or some internal barrier, perhaps.

- What will the character do about the problem? It’s better to have characters earn their objectives by their own efforts, rather than by luck or coincidence.

- Why don’t the character’s efforts work? Use events and dialogue in the scene to challenge your character. Introduce twists and turns. Don’t make the problem easy.

- How will this ‘microplot’ end? If with success, you’ll satisfy reader expectations. If with failure, at least you’ve got the reader rooting for your character as the book goes on.

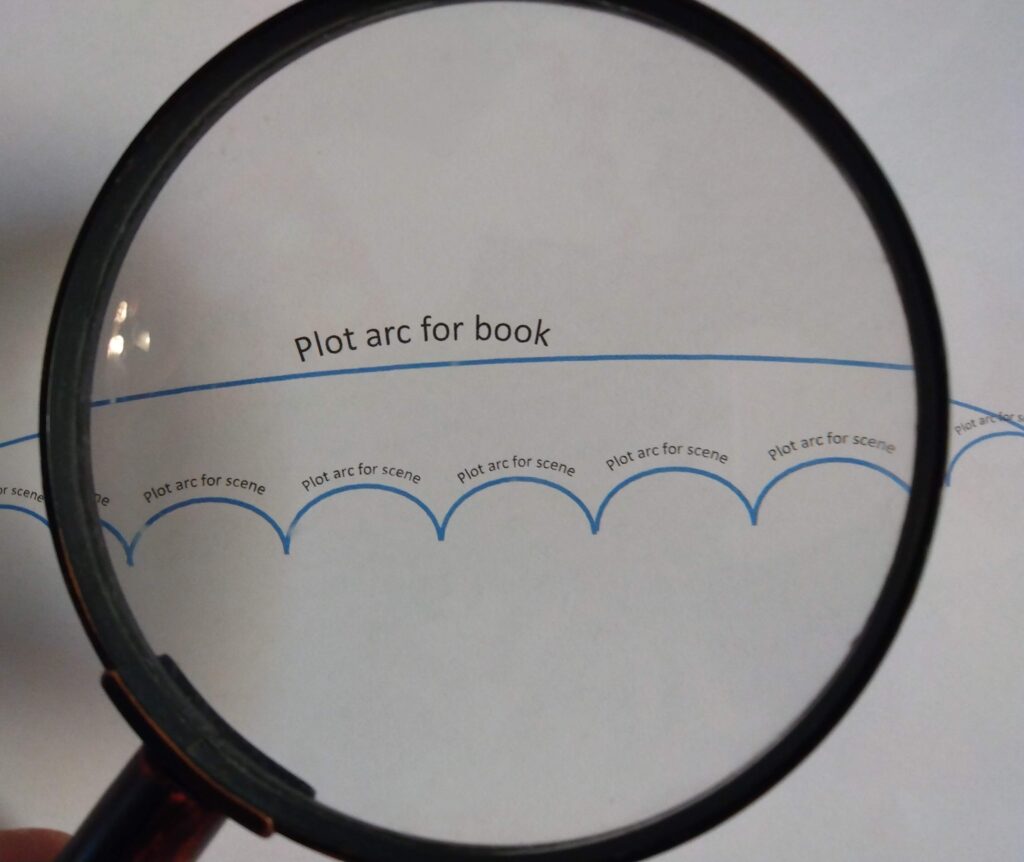

Just as a magnifying glass reveals small and interesting details that make up a whole picture, so your microplots keep a reader fascinated enough to make it through your whole book.

Be careful with your magnifying glass, though. Don’t misuse it to burn up any books by—

Poseidon’s Scribe