On occasion, I

blog about the ways society reacts to new technology. Today I’ll consider the

life-cycle of a technology.

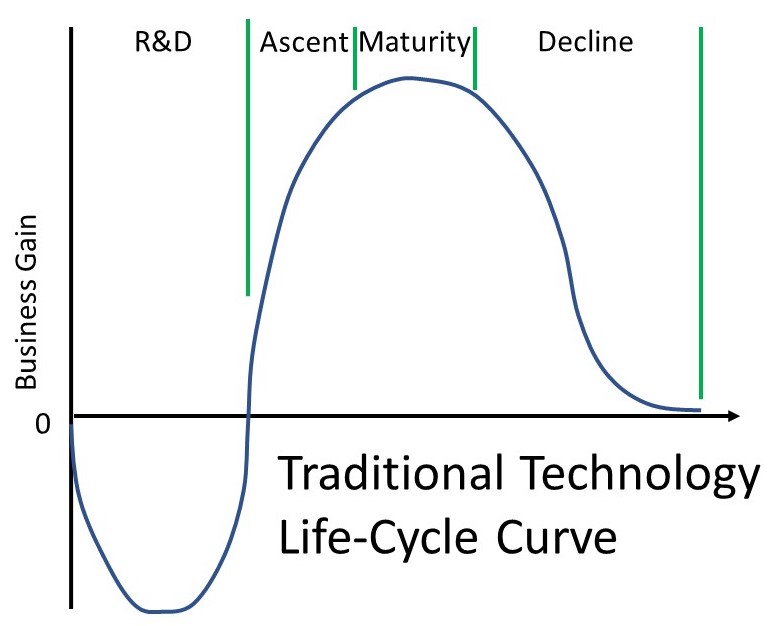

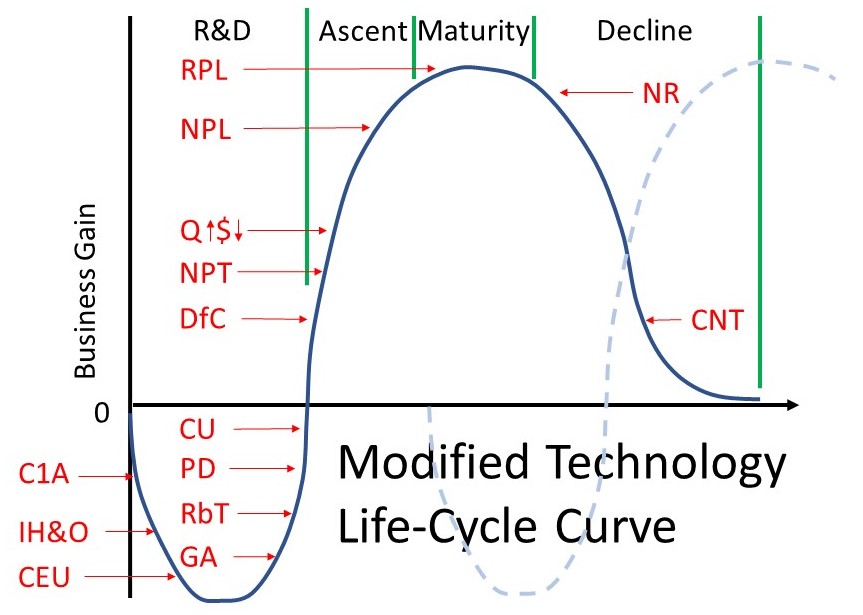

Graphing a technology’s life-cycle isn’t new. You can see this graph on Wikipedia. It’s the standard view of the profitability of a new technology over its life, including the four phases: Research and Development, Ascent, Maturity, and Decline.

I’ve built on

the standard technology life-cycle curve by adding several points of interest

to it. These don’t occur with every technology, and don’t always appear in the

same order. But they are common enough that I’ve seen them frequently. These points

of interest fascinate me, and I explore them in my fiction.

C1A. Clumsy First Attempts. Often the

first prototypes of a technology are crude, fragile, ugly things that only a laboratory

scientist could love. In no way do they resemble a marketable product. On occasion,

these breadboard prototypes do not work at all.

IH&O. Initial Hype and Overpromise. When

dreamy-eyed advocates of the new technology get hold of a gullible press, news articles

will appear about the technology, touting the marvelous future that awaits us

all when the technology revolutionizes our lives. Sure.

CEU. Careful Early Use. Particularly

when a new technology involves some danger or personal risk, the researchers

proceed in a deliberate, methodical manner in testing it. They take safety precautions.

They go step-by-step, fully aware of the hazards. This is good, but it contrasts

with the CU point occurring later.

GA. Gaining Adherents. Some technologists

call these people ‘early adopters.’ They can hardly wait for the technology to

hit the market. They’ll stand in line to be the first to buy.

RbT. Reaction by Traditionalists. People

accustomed to older technology will be quick to point out any defects in the new

one, even if there are far more advantages than disadvantages. They are

resistant to change, but won’t admit it. Instead, they will seek out the

slightest reason to criticize as a way of rationalizing their resistance. They

start with “It’ll never work,” then after it does, they’ll say, “It’ll never

catch on.”

PD. Path Dependence. I’ve blogged about this phenomenon before. Developers of new technology will imitate the appearance and terminology of existing technologies. This tendency will be abandoned later at the DfC point, but it often characterizes and constrains new technology, while at the same time making it easier to relate to.

CU. Complacent Use. After a long

period of successful testing, researchers will reach a comfort level with the

new technology. They will abandon the care and precautions they employed at the

earlier CEU point. This complacence can result in a bad outcome, a failure. If

this occurs, they will refine the technology to correct flaws before marketing

it to users, who will also grow complacent and not treat risky technology with

respect.

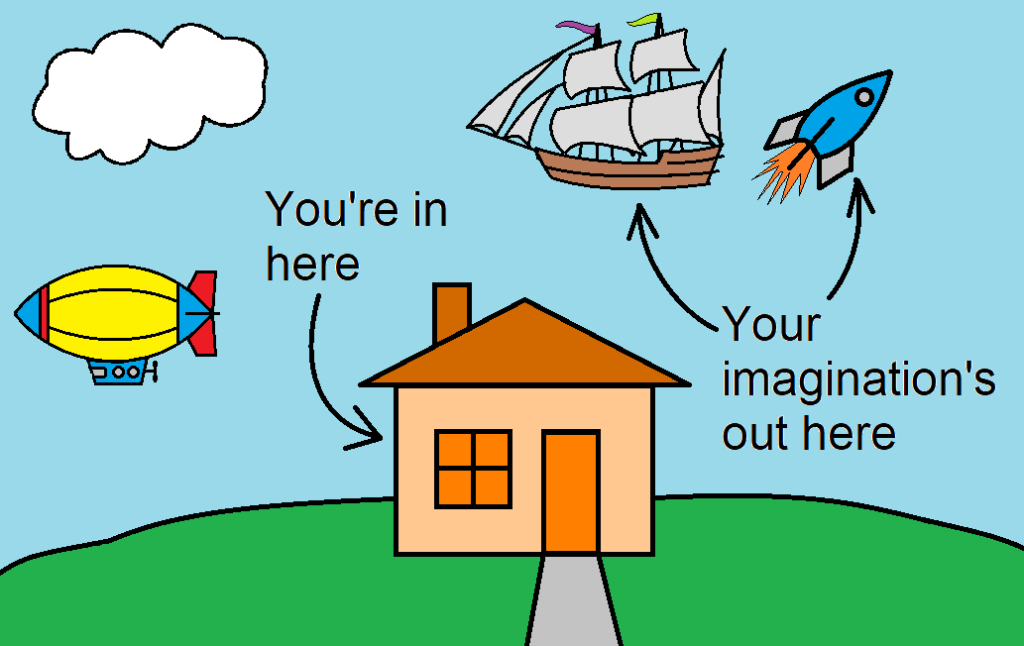

DfC. Departure from Constraints. At

some point, developers and imitators free themselves from the Path Dependence

tendency. They start to explore the realm of possibilities of the new

technology, no longer bound by past precedent.

NPT. Nostalgia for Previous Technology.

This is similar to RbT, but slightly different. We expect traditionalists to

object to new technology, but at this point, even some regular users—advocates

of the new tech—begin to pine for the previous technology. They miss it,

recalling its advantages and forgetting its quirks.

Q?$?. Quality Up, Price Down. At this point, the technology comes into its own. Original developers, as well as imitators/competitors, improve the technology and the means of producing it. Price drops and product quality improves. It’s a period of rapid growth and acceptance, a boom time.

NPL. Nearing Physical Limit. Late in

the Ascent phase, producers or users begin to sense that things can’t go on. The

technology is bumping up against some limitation, or has begun to cause an

unanticipated problem, or is fast consuming some scarce resource. Producers try

some tweaks to counter the problem, to hone the technology so as to mitigate the

impending limit.

RPL. Reached Physical Limit. At the peak

of the Maturity phase, when the technology is providing the most profit to

producers, it can go no further. It cannot be improved sufficiently to overcome

whatever limitation constrains it.

NR. Negative Reaction. Users start rejecting the technology, blaming it for the problems it caused. Engineers and researchers cast around for possible replacement technologies. Market demand and profits both plummet.

CNT. Competition with New Technology.

In this period of chaos, the technology struggles against an emerging rival. The

technology is fated to either die entirely or steady out at some low level,

continuing to be used by die-hards who prefer it to its replacement.

There you have

it, your newly-labeled technology life-cycle curve, provided by—

Poseidon’s Scribe