The latest outrage jolting the fiction-writing world is the Cristiane Serruya Plagiarism Scandal, or #CopyPasteCris in the Twitter world. I’ll leave it for others to gnash teeth and rend garments over the specifics of this case. As a former engineer and natural problem-solver, I prefer to look at what we might do to prevent future recurrences.

First, let me summarize. Alert and avid readers of romance books noticed matching phrases and paragraphs in two books: The Duchess War (2012) by Courtney Milan and Royal Love (2018) by Cristiane Serruya. These readers notified Ms. Milan, who reacted strongly. More investigations by readers of Ms. Serruya’s 30-odd books found uncredited passages and excerpts from 51 other books by 34 authors, 3 articles, 3 websites, and 2 recipes. In addition to Ms. Milan, the original authors included Nora Roberts, who likewise doesn’t tolerate imitation, no matter how sincere the flattery.

While lawyers gather for the coming feast, let us back away from the immediate affair, make some assumptions about the problem, and consider possible solutions. First, we’ll assume Ms. Serruya actually did what readers allege, that she (or her hired ghostwriters) copied other works and passed them off as her own. Second, let’s assume she is at least somewhat sane and had semi-logical reasons for doing so. Third, we’ll assume Ms. Serruya is not alone, that there are others out there doing the same thing.

What might her motivations have been? Why would anyone do this? In her post, Ms. Roberts asserts the existence of “black hat teams” working to thwart Amazon’s software algorithms to maximize profit. For more on this practice, read Sarah Jeong’s post from last summer, based on the Cockygate scandal.

It’s possible we’ve reached a point where (1) the ease of copying books, (2) the money to be made by turning out large numbers of romance books, and (3) the lack of anti-plagiarism gatekeepers at Amazon, have combined to produce all the incentive needed for unscrupulous “authors” (even a cottage industry of them) to copy the work of others.

Setting aside the current scandals, which must be resolved in light of existing laws and publishing practices, what can we do to prevent this in the future? How would we arrange things to dissuade future imitators of Ms. Serruya? What follows are four potential solutions, listed in order from least desirable to my favorite.

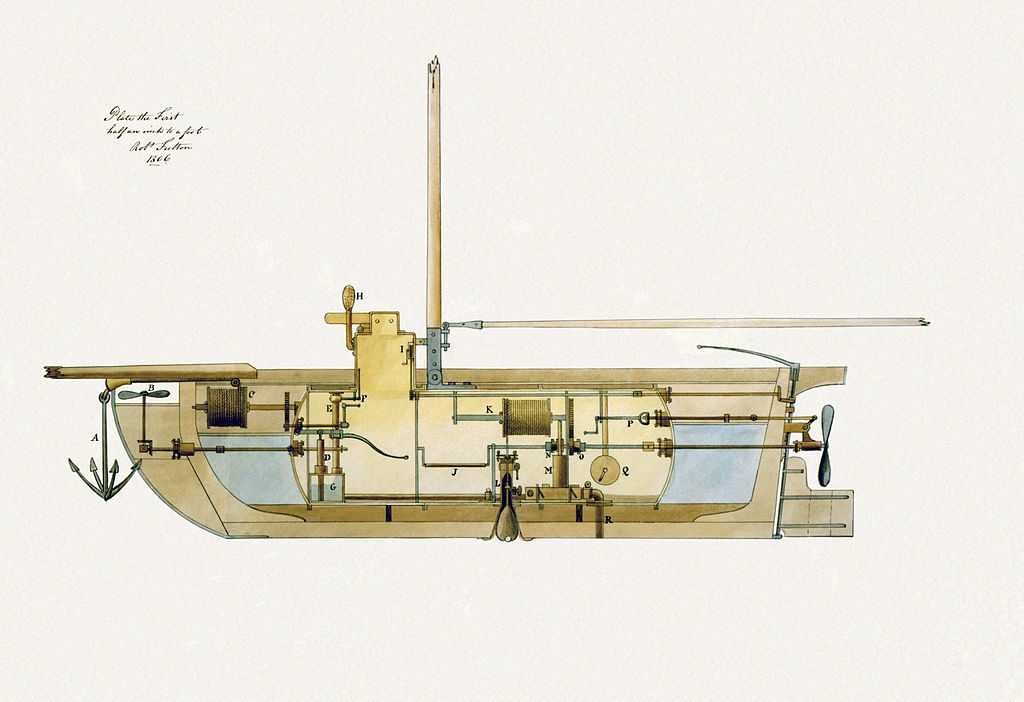

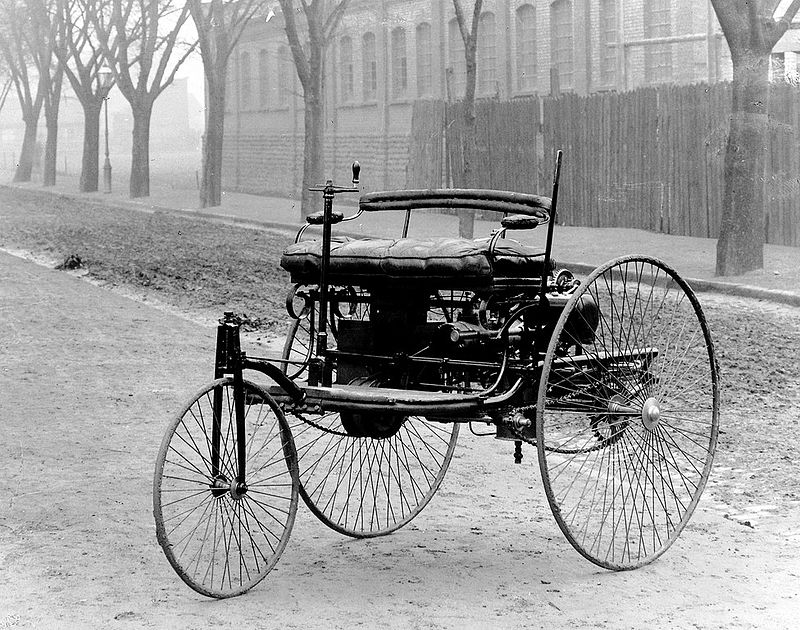

- Make Copyrights like Patents. Consider how copyrights differ from patents: they’re free; they’re automatic; they require no effort by the government. For a patent, though, you must pay the government to determine if your invention is distinctly different from previous patented devices. If the government grants your patent, you then have full government support and sanction for your device, and a solid legal foundation to go after those who dare to infringe. We could do the same with copyrighting books. Boy, would that ever slow down the publishing world!

- Make Amazon a Better Gatekeeper. Amazon and other distributors could set up anti-plagiarism software that detected if a proposed new book contained too many copied phrases from other books. Then they’d simply refuse to publish books that didn’t pass that algorithm. Although pressure from customers might force Amazon to do that, it’s not likely to happen, as explained by Jonathan Bailey in this post.

- Make Use of Private Plagiarism-Checking Services. Imagine if a private company offered (for a fee) to check your manuscript to see if you’d plagiarized. Assuming your manuscript passed, you would cite that acceptance when you published it, similar to the Underwriters Laboratory model for electrical systems. Readers might tend to select plagiarism-checked books over those not certified. This would put a financial burden on authors.

- Trust Readers. We could rely on astute readers to detect plagiarism, to notify the affected author, and to use social media to shame the plagiarizer publicly. This is, of course, where we are today. It requires no new laws, no fees, and no algorithms. It’s not perfect, but so far, it is proving workable.

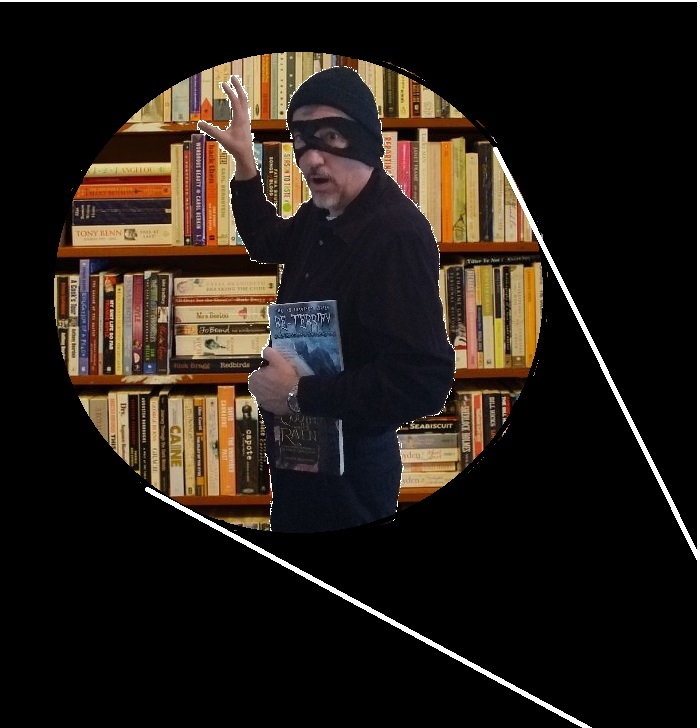

If you think of other, better solutions, please leave a comment. Oh, and in case you were wondering, I wrote every word of my stories. Just ask my alter ego—

Poseidon’s Scribe