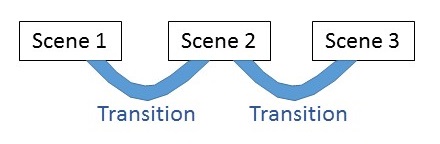

Alfred Hitchcock said, “Drama is life with the dull bits cut out.” True, but you can’t just write the interesting bits and call that collection of scenes a story. You must connect those scenes in a smooth, seamless way. Today’s post is about these connections, called transitions.

I Iike the way Jody Hedlund described transitions in her post, as tunnels for transporting readers from scene to scene. Without these tunnels, readers would feel disoriented and confused. However, the tunnel itself is boring, so it’s best not to linger there. Keep your transitions short.

In Beth Hill’s post on the subject, she cites the three usual types of transitions: (1) change in time, (2) change in location, and (3) change in point of view. She also discusses transitions as a way to show a (4) change in mood or frame of mind. You can also use these types in combination.

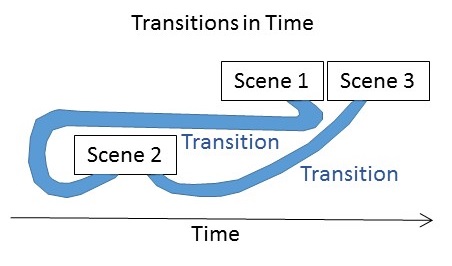

With time transitions, a subsequent scene takes place at a different time than the previous scene. You can separate your scenes by minutes, weeks, months, years, centuries, or millennia. In the case of flashbacks, you can even go backwards in time. It’s important to make clear to the reader how far in time, and in which temporal direction, the new scene is from the previous one.

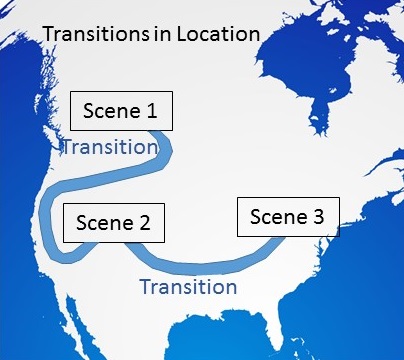

Location transitions shift the new scene to a different place. Once again, make it obvious to the reader that the story has shifted elsewhere. Spend only as many words as you need to describe the new setting, so the reader feels she is there with the characters.

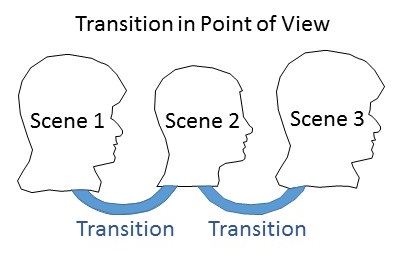

Point of View transitions can be tricky. It’s best to mention the name of the new POV character early in the scene, in the first sentence. Since no two characters think alike, start by having the new POV character think about something the previous scene’s POV character wouldn’t have, to make the transition more obvious to the reader.

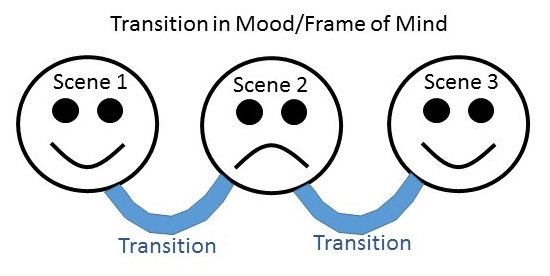

You can combine mood transitions with the other types, and often a change in time or location explains the change of mood. If a character alters mood within a scene, you need to make reason for the change clear to the reader.

Some writers find transitions difficult to write. If that’s true for you, consider writing your scenes first and just skip the transitions. Then go back and write those transitions, focusing on helping the reader understand when the new scene is, where it is, and from whose point of view she’s seeing it. Make the change obvious and brief.

As you edit transitions, read the end of the previous scene, the transition, and the beginning of the following scene. Is the change clear? Is it too abrupt, or too long?

So, follow the advice of Alfred Hitchcock and cut out the dull bits, but make sure you transition well between the remaining dramatic scenes. Now, transitioning to my usual sign-off, I’m—

Poseidon’s Scribe