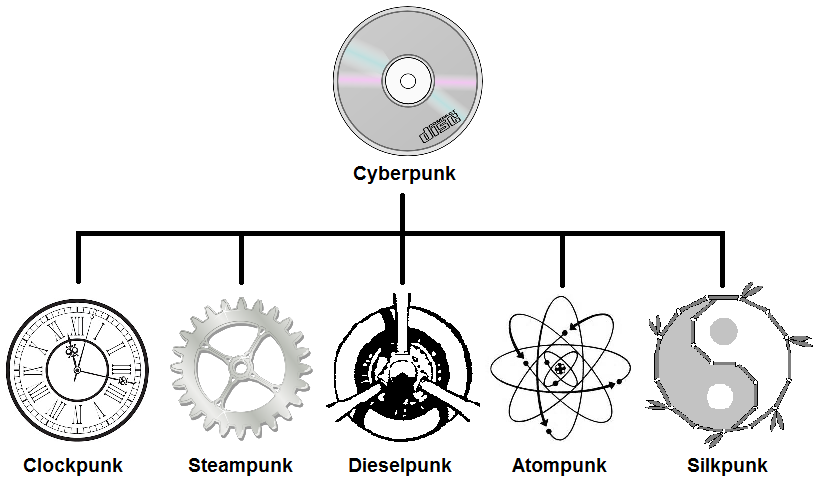

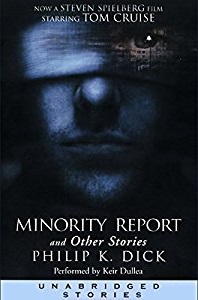

You thought this blog-post was the last word on the various ‘punk’ subgenres? Wrong. Meet the new member of the punk family: Silkpunk.

Author Ken Liu invented the term Silkpunk to describe the genre of his latest novel, The Grace of Kings. In this post, he defined silkpunk as “…a blend of science fiction and fantasy…[drawing] inspiration from classical East Asian antiquity. My novel is filled with technologies like soaring battle kites that lift duelists into the air, bamboo-and-silk airships propelled by giant feathered oars, underwater boats that swim like whales driven by primitive steam engines, and tunnel-digging machines enhanced with herbal lore.”

This newest member of the Punk Family is unlike the others in that it’s not represented by a power source or engine type. Perhaps, though, in a metaphorical way, it is. The Silk Road was a trade network from China to Europe that empowered China.

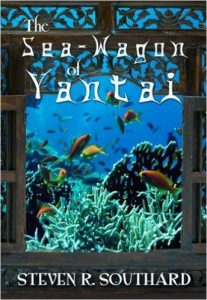

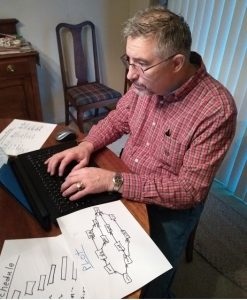

Congratulations to Mr. Liu for coming up with the term Silkpunk. However, with all due modesty, I must say, stories of that type are not new. My own story, “The Sea-Wagon of Yantai” belongs in that genre as well.

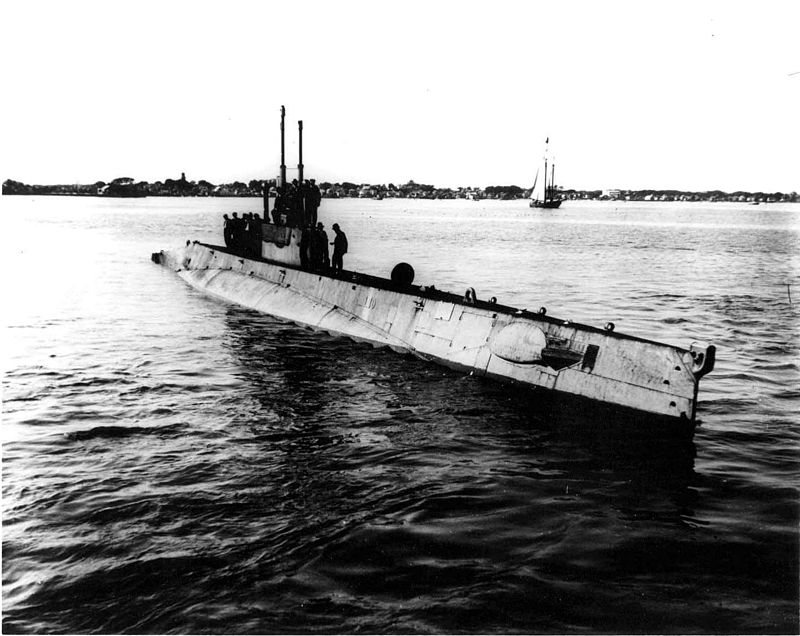

In my tale, it’s 206 B.C. and China is torn by warring dynasties. A young warrior, Lau, receives orders to verify the legend of a magic wagon that can cross rivers while remaining unseen. He encounters Ning, the wagon-maker in the seaside village of Yantai. Ning has constructed an unusual wagon that can submerge, travel along the bottom of the Bay of Bohai, and surface in safety—the world’s first practical submarine. Ning enjoys the peace and beauty of his undersea excursions; he won’t allow the military to seize his wagon or learn its secrets. Lau must bring the valuable weapon back to his superior. In the hands of these two men rest the future of the submarine, as an instrument of war or exploration.

In my tale, it’s 206 B.C. and China is torn by warring dynasties. A young warrior, Lau, receives orders to verify the legend of a magic wagon that can cross rivers while remaining unseen. He encounters Ning, the wagon-maker in the seaside village of Yantai. Ning has constructed an unusual wagon that can submerge, travel along the bottom of the Bay of Bohai, and surface in safety—the world’s first practical submarine. Ning enjoys the peace and beauty of his undersea excursions; he won’t allow the military to seize his wagon or learn its secrets. Lau must bring the valuable weapon back to his superior. In the hands of these two men rest the future of the submarine, as an instrument of war or exploration.

My story was inspired by vague references I’d read about someone inventing a submarine in China around 200 B.C. A second inspiration for my story was Ray Bradbury’s tale, “The Flying Machine.” One of his lesser-known works, it’s a wonderful short story, and would certainly qualify as silkpunk, with its kite-like bamboo flying machine with paper wings.

Another silkpunk story that predates the invention of the subgenre’s name is “On the Path,” by fellow author Kelly A. Harmon. Within it, Tan is a farmer, following the path, when the seal on his soul-powered plow bursts, releasing all ghosts from its reincarnation engine. The ghosts flee to Tan’s tangerine groves, reveling in their freedom. One of the souls is Tan’s deceased uncle, Lau Weng, and Tan must offer hospitality. Souls laboring in the reincarnation engines grow more solid as they work off their past lives’ debts and prepare to be born again. Freed from the engine, Lau Weng and his ghostly compatriots rely on Tan and his wife Heng to support them. Caught between death and re-birth, Lau Weng will do anything to remain alive. Tan is honor-bound to provide hospitality, but must feed his family, too, and he can do nothing to stop Lau Weng. Everything changes once Lau Weng takes over Heng’s body.

Another silkpunk story that predates the invention of the subgenre’s name is “On the Path,” by fellow author Kelly A. Harmon. Within it, Tan is a farmer, following the path, when the seal on his soul-powered plow bursts, releasing all ghosts from its reincarnation engine. The ghosts flee to Tan’s tangerine groves, reveling in their freedom. One of the souls is Tan’s deceased uncle, Lau Weng, and Tan must offer hospitality. Souls laboring in the reincarnation engines grow more solid as they work off their past lives’ debts and prepare to be born again. Freed from the engine, Lau Weng and his ghostly compatriots rely on Tan and his wife Heng to support them. Caught between death and re-birth, Lau Weng will do anything to remain alive. Tan is honor-bound to provide hospitality, but must feed his family, too, and he can do nothing to stop Lau Weng. Everything changes once Lau Weng takes over Heng’s body.

Thanks to Ken Liu (and others), silkpunk may well catch on in popularity in North America and Europe. Here are four reasons why:

- Like steampunk, silkpunk comes ready made with its own aesthetic, with fascinating clothing for costumes, and a characteristic look for gadgets, etc.

- Silkpunk is a completely new world, ripe and wide open for writers and readers to explore.

- To Western readers, silkpunk will seem exotic and enthralling.

- For Western readers, silkpunk represents a chance to learn about new cultures and different philosophies.

Will Silkpunk someday rival Steampunk in popularity? I don’t know. I’m a writer. If you want a psychic, don’t call—

Poseidon’s Scribe

Sitting at your computer, you produce your first work product of the day. (What’s the product? I don’t know; we’re talking about your current day job.) You e-mail it to your boss and wait. A few hours later, your boss e-mails you back to say the product didn’t suit her needs. She says she can’t accept it.

Sitting at your computer, you produce your first work product of the day. (What’s the product? I don’t know; we’re talking about your current day job.) You e-mail it to your boss and wait. A few hours later, your boss e-mails you back to say the product didn’t suit her needs. She says she can’t accept it.

I didn’t hire a professional photographer.

I didn’t hire a professional photographer.