One of inventor Thomas Edison’s most famous quotes is, “Genius is one percent inspiration, ninety-nine percent perspiration.” There may be a similar ratio involved with writing fiction, too. Let’s find out what it is.

I got the idea for this post while reading a wonderful guest post by author Anthony St. Clair on Joanna Penn’s website. St. Clair takes the extreme view that a writer should forget the muse and just show up for work and produce prose.

For discussion’s sake, let’s postulate two possible aspects of writing fiction called Creativity and Productivity. Here are the attributes for each:

| Creativity | Productivity |

| · Wait for the muse | · No waiting—get to work |

| · Muse whispers in your ear | · Invisible boss yells at you |

| · Book idea is fully formed | · Book emerges from long process |

| · Words flow like water | · Words extracted with pliers |

| · Pleasantry | · Drudgery |

| · 1st draft = final draft | · 1st draft = crap |

| · Mind to universe | · Nose to grindstone |

| · Work late at night | · Work efficiently |

| · Write in binges to exhaustion | · Write on schedule to completion |

| · Guided by insight and instinct | · Guided by plan and outline |

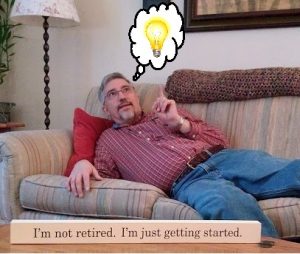

| · Lying on couch, thinking | · Sitting at desk, working |

| · Great ideas per lifetime | · Words per day |

If fiction writing consists of some amalgamation of those two aspects, what is the ratio between the two? St. Clair’s post advocates a ratio of 0% creativity and 100% productivity.

I can’t go quite that far. I agree it’s necessary to dispel the myth some beginning writers have about writing being all Creativity. Sadly, it’s not. If you wish to write, steel yourself to suffer through the items on the Productivity list. Most writing consists of enduring the attributes in the right column.

Most, but not all. There is, and has to be, some amount of stuff from the Creativity side of the ledger.

For me, the two aspects occur at different times and in different settings. Productivity occurs when I’m sitting at the desk typing, or when I have a pad handy and I’m writing by hand.

Creativity occurs when I’m doing some other activity that doesn’t require full brain engagement, such as yardwork, showering, or exercising. In other words, the Creativity part of writing happens when I’m not writing. Apparently, idle neurons spark best at those times. That’s when I conjure up new story ideas, work out plot problems, flesh out characters, imagine settings, etc.

The ideas ignited during those non-writing creative times remain with me and guide me when I sit down to do actual writing. They either form my plan or modify an existing plan.

To muddy things a bit, there are elements of Creativity within the Productivity sessions and vice versa. There are times, at the keyboard, when I get stuck and must summon my creative side for help. Likewise, my Creative moments often involve a measure of directed thought, not just waiting for muse whisperings.

Moreover, the Creativity/Productivity ratio changes during the development of a story. Early on, it’s nearly all Creativity. In the editing and polishing stages, the work shifts almost wholly to Productivity.

Given all that, what is my answer to the original question—the creativity/productivity ratio? In terms of importance or value to the process, I’d say it’s 50-50. Both parts are necessary. However, in the amount of time spent, I’d estimate fiction writing is one part Creativity and nine parts Productivity. At least, that’s the ratio for—

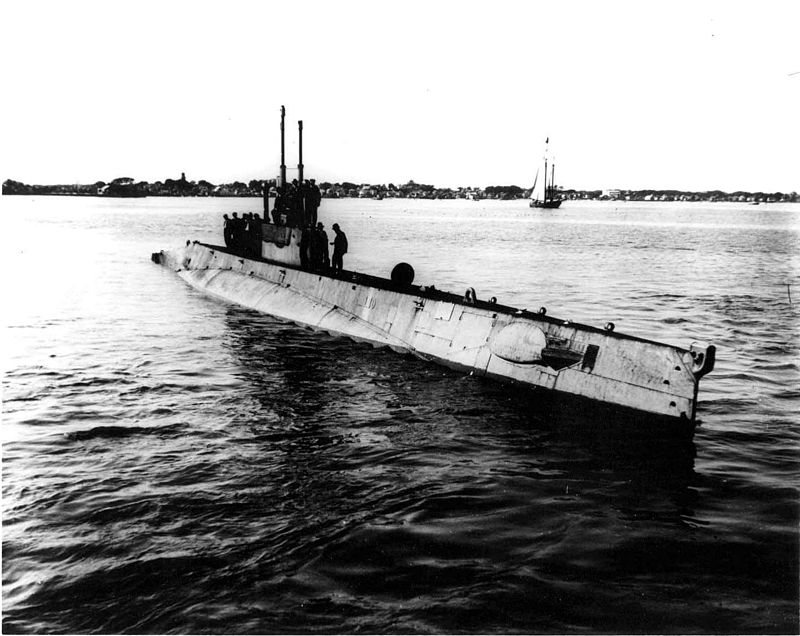

Poseidon’s Scribe

Sitting at your computer, you produce your first work product of the day. (What’s the product? I don’t know; we’re talking about your current day job.) You e-mail it to your boss and wait. A few hours later, your boss e-mails you back to say the product didn’t suit her needs. She says she can’t accept it.

Sitting at your computer, you produce your first work product of the day. (What’s the product? I don’t know; we’re talking about your current day job.) You e-mail it to your boss and wait. A few hours later, your boss e-mails you back to say the product didn’t suit her needs. She says she can’t accept it.