When you’re stuck for a story idea, it may seem like other authors have already written all the good tales. Every time you think of a plot, for example, your head swims with titles that have covered that plot, worn it thin.

Are there only so many plots, you wonder, peopled with different characters, set in different places and times, portraying different themes, and written in different tones and styles?

Others have wondered that before you, and developed their own lists of all plot types. Prepare to be confused, and then (perhaps) unconfused.

Others have wondered that before you, and developed their own lists of all plot types. Prepare to be confused, and then (perhaps) unconfused.

In his 2004 book, The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories, Christopher Booker declared there are seven plot types: Overcoming the Monster, The Quest, The Voyage and Return, Rags to Riches, Rebirth, Comedy, and Tragedy.

One year earlier, Ronald B. Tobias came out with his book, 20 Master Plots: And How to Build Them. His list included plots such as Revenge, Transformation, and Wretched Excess.

One year earlier, Ronald B. Tobias came out with his book, 20 Master Plots: And How to Build Them. His list included plots such as Revenge, Transformation, and Wretched Excess.

Much earlier, in 1916, the book The Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations by Georges Polti introduced thirty-six plot categories, including Obtaining, Rivalry of Superior and Inferior, and Loss of Loved Ones.

Much earlier, in 1916, the book The Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations by Georges Polti introduced thirty-six plot categories, including Obtaining, Rivalry of Superior and Inferior, and Loss of Loved Ones.

Great, you’re thinking, but how many are there—seven, twenty, or thirty-six? That depends on the way you like to categorize things. You could cut a pizza into seven, twenty, or thirty-six pieces, and they’d still add up to the same pie.

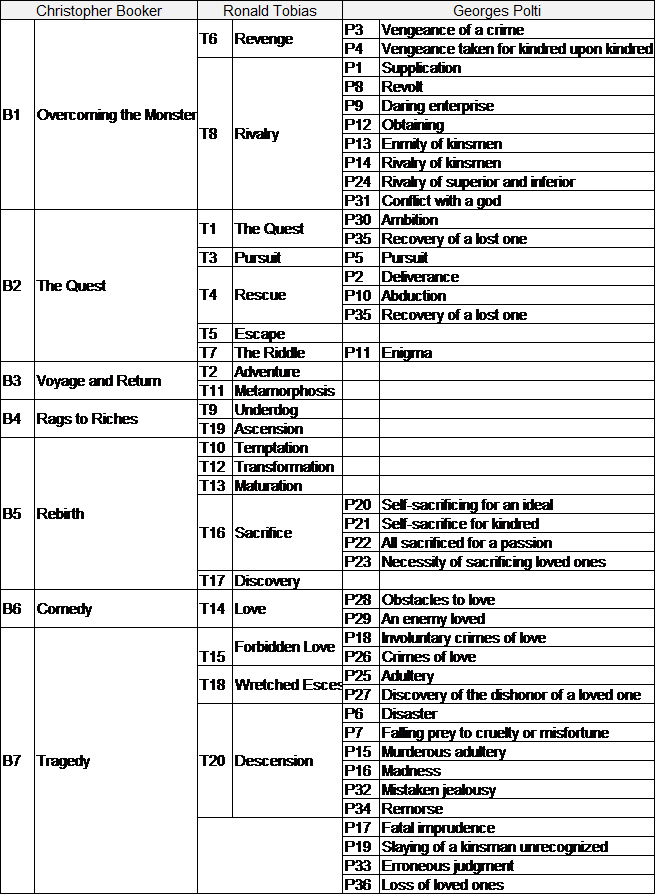

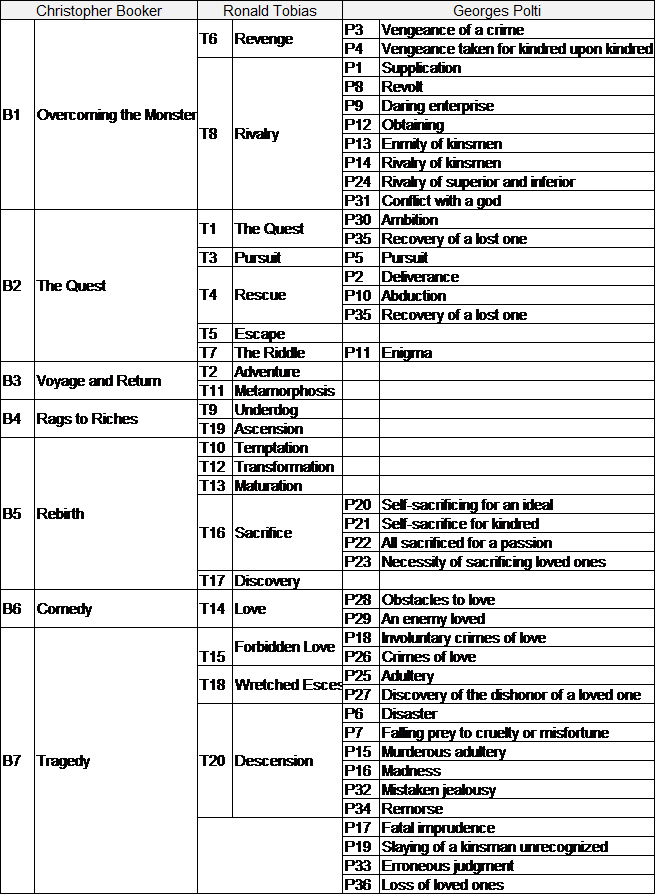

That’s what I wanted to explore today. How do those categorization schemes compare to each other? Can you take Booker’s seven plots and see where Tobias’ twenty fit into them? Do Polti’s thirty-six plots fit somehow with Tobias’ and Booker’s taxonomies?

I couldn’t find any example of someone doing this, so I did it. I designated each of Booker’s categories with a B-number: B1, B2, etc. I did similarly with Tobias’ 20 (T1, T2, etc.) and Polti’s 36 (P1, P2, etc.)

Then the trouble started. Many didn’t fit well at all. In such cases, I read the descriptions the authors gave for their categories and chose the one in the other’s categories that seemed most like the one I was considering. You may disagree with the way I’ve mapped them, and I’d love to know your reasoning.

For your careful study, wry amusement, and utter disgust, here is my mapping of the three plot schema against each other:

By now, some questions have occurred to you. One might be, “Can’t a single story be a mixture of two or more of those plot types?” Answer: Yes, there’s no law against that.

Others of you are asking, “Why are the love stories listed as comedies?” Answer: Booker defined his comedy category as including more than humorous stories, and in particular included love stories in that group.

Lastly, there are those asking, “Of what use is this map? Come to think of it, of what use are the three taxonomies?” Answer: for those who asked that, I have no answer that will satisfy you. Go ahead and just write any old story whether it fits a pre-discovered plot category or not.

For those who didn’t ask that last question, you’re probably comfortable with the fact that some people like to take a mass of data and try to organize it somehow, to create filing categories like a Dewey decimal system or biological taxonomies.

Whether you think there are seven, twenty, or thirty-six plot types, or if you don’t see the point in dividing that pizza at all, there are plenty of stories remaining for you to write. Let’s see if the next one you create will be better than any authored by—

Poseidon’s Scribe

It’s insane, really. Smashwords slashed the price for every single book in my What Man Hath Wrought series. The ones that were $3.99 are now $2.00 and the ones that were $2.99 are just $1.50. But only for the rest of today.

It’s insane, really. Smashwords slashed the price for every single book in my What Man Hath Wrought series. The ones that were $3.99 are now $2.00 and the ones that were $2.99 are just $1.50. But only for the rest of today.

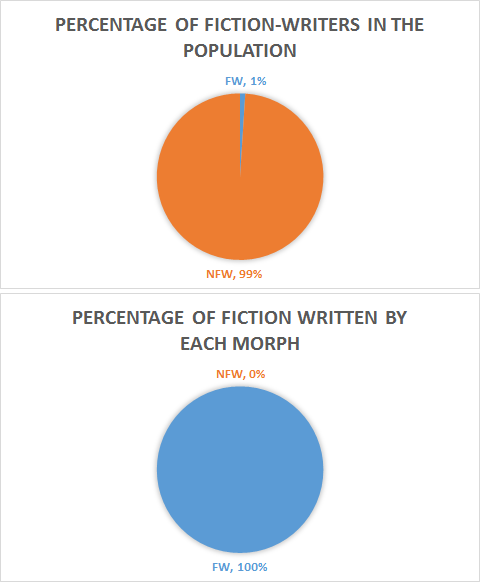

Observations indicate the vast majority (greater than 99 percent) of adults within this species do not write fiction. The fiction-writing and non-fiction-writing fractions have not split off as separate species, and seem unlikely to do so. The distinction between the two is behavioral only, so we may define the fiction-writers as the FW Morph, and the others as the NFW Morph. Other sub-species terms such as breed, race, cultivar, ecotype, and strain are not as applicable as morph.

Observations indicate the vast majority (greater than 99 percent) of adults within this species do not write fiction. The fiction-writing and non-fiction-writing fractions have not split off as separate species, and seem unlikely to do so. The distinction between the two is behavioral only, so we may define the fiction-writers as the FW Morph, and the others as the NFW Morph. Other sub-species terms such as breed, race, cultivar, ecotype, and strain are not as applicable as morph. In an economic sense, it is fortunate that FWs are in the minority; otherwise they would have to pay NFWs to read their books, rather than the other way around.

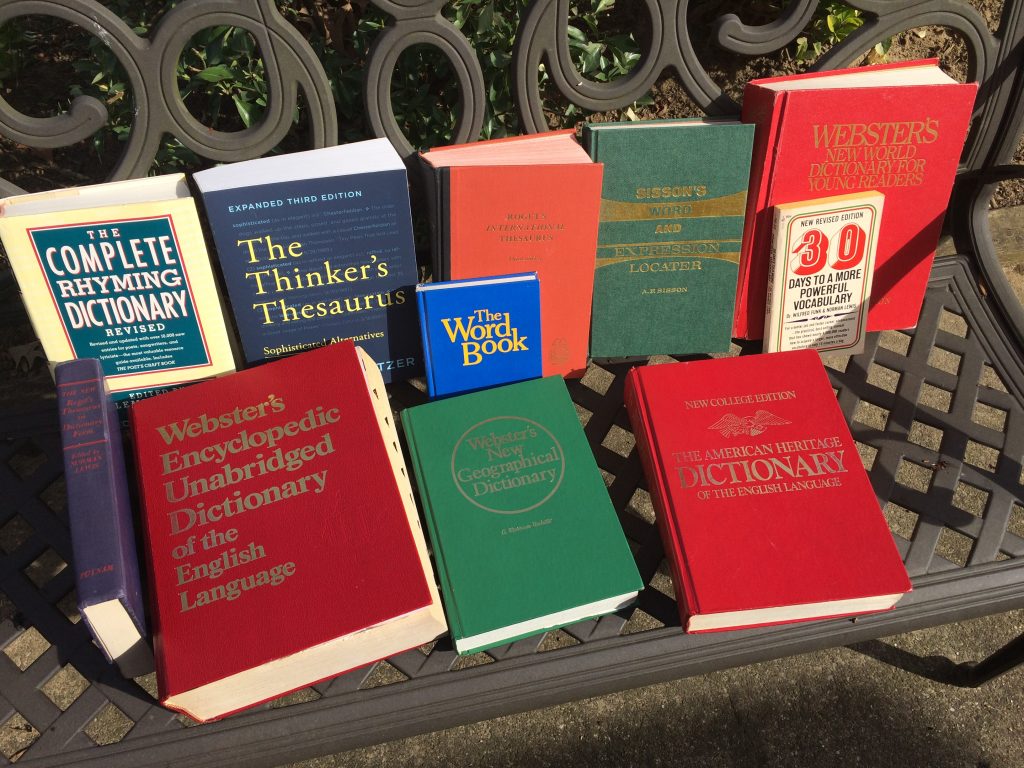

In an economic sense, it is fortunate that FWs are in the minority; otherwise they would have to pay NFWs to read their books, rather than the other way around. I’ll define Leximania as an intense love of—bordering on obsession with—words. It’s not necessary to have leximania to be a writer…but it helps. After all, to a writer, words are like a sculptor’s clay, a composer’s musical notes, a painter’s palette and brush. Words are the tiny bits of noting which, when joined, make literature. They’re the atoms of a writer’s universe, so it’s understandable if writers take an unusual level of interest in them.

I’ll define Leximania as an intense love of—bordering on obsession with—words. It’s not necessary to have leximania to be a writer…but it helps. After all, to a writer, words are like a sculptor’s clay, a composer’s musical notes, a painter’s palette and brush. Words are the tiny bits of noting which, when joined, make literature. They’re the atoms of a writer’s universe, so it’s understandable if writers take an unusual level of interest in them.

But why should you want to be a writer in the first place? That is a question never answered in any of my posts…until now.

But why should you want to be a writer in the first place? That is a question never answered in any of my posts…until now.

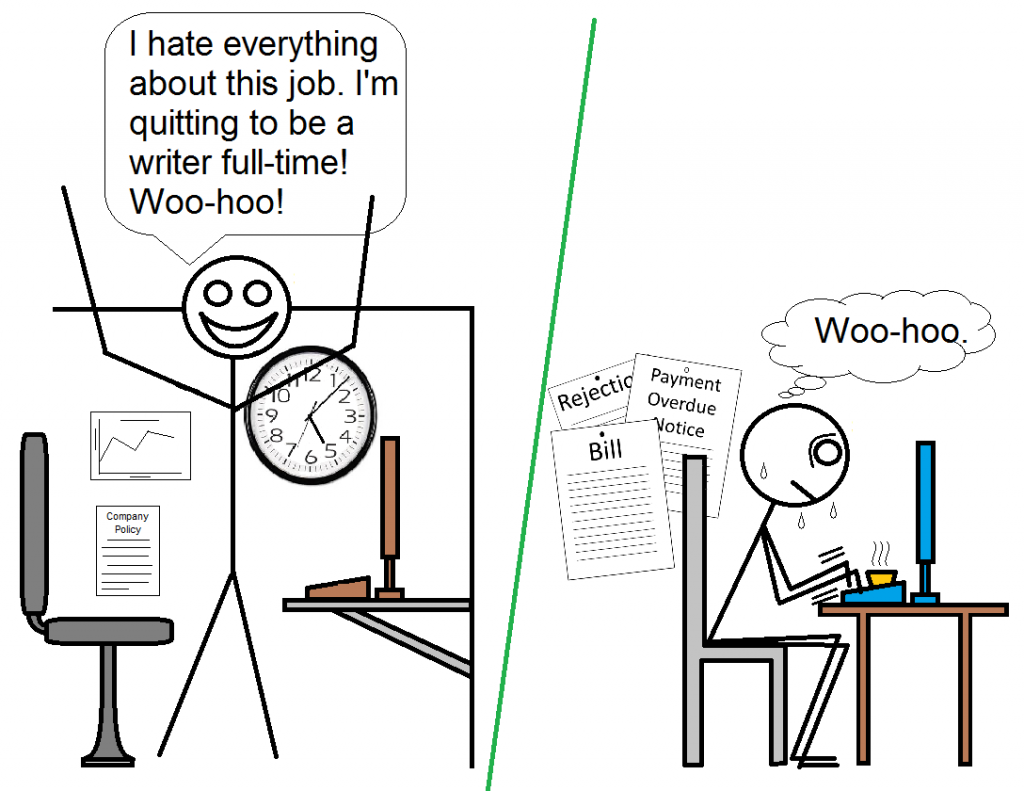

You’ve been writing fiction as a hobby at home for some time now, and have sold a few stories, received payment as a published author. What if…

You’ve been writing fiction as a hobby at home for some time now, and have sold a few stories, received payment as a published author. What if… That’s right. You must edit your own work before submitting it. Attack it with all the dispassionate, ruthless vigor you can. Hack, cut, and tweak until you fashion it into a story that makes you proud. Only that will make it publishable.

That’s right. You must edit your own work before submitting it. Attack it with all the dispassionate, ruthless vigor you can. Hack, cut, and tweak until you fashion it into a story that makes you proud. Only that will make it publishable.

Since humorous writing is so tough to get right, why don’t we forget the whole thing? For one, if we can manage to tell a funny story, readers like it. An amusing tale lifts them from the gloomy tedium of their dreary lives, the poor things. Think of it as a public service, kind of a ‘clown-author saves the world’ idea.

Since humorous writing is so tough to get right, why don’t we forget the whole thing? For one, if we can manage to tell a funny story, readers like it. An amusing tale lifts them from the gloomy tedium of their dreary lives, the poor things. Think of it as a public service, kind of a ‘clown-author saves the world’ idea.