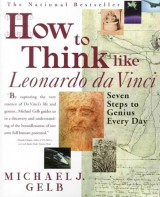

Some time ago, I promised to write seven separate blog posts, one for each of the principles espoused in How to Think like Leonardo da Vinci, by Michael J. Gelb. I said I’d relate them to writing fiction. This is the first post in that series.

The first principle is Curiosità, which Gelb defines as “an insatiably curious approach to life and an unrelenting quest for continuous learning.” He discusses Leonardo’s curiosity and provides worthwhile exercises for developing your own inquisitiveness. (I encourage you to buy his book and to work through the exercises.)

The first principle is Curiosità, which Gelb defines as “an insatiably curious approach to life and an unrelenting quest for continuous learning.” He discusses Leonardo’s curiosity and provides worthwhile exercises for developing your own inquisitiveness. (I encourage you to buy his book and to work through the exercises.)

Fiction writers must have boatloads of curiosity. They must ponder things like:

What is the meaning of life?

What is the meaning of life?- Why do people behave as they do?

- What do readers want from books?

- What is the meaning and origin of this or that interesting word?

- How do I improve my writing?

- What would happen I twisted this real-world situation around differently?

- What would that setting be like?

- How would my protagonist act in this situation?

- etc…

On and on forever. Moreover, each answer sparks five more questions.

Curiosity is something you once had, then lost, and now must strive to regain. When you were four or five years old, you were intensely, ravenously curious. You barely had the language skills to form questions, but you asked hundreds of them. We all did, at that age. We especially liked questions starting with “why.”

Then older people and life experiences supplied answers. Some adults told you religion had your answers; some said science did; some said both. They gave you books to read, hoping to satisfy you.

Some answers discouraged further inquiry. Few answers satisfied you at first, but later you came to accept, to believe. You learned societal taboos and sensitive areas. You tamped down your curiosity and asked fewer questions.

Lately, you’ve grown accustomed to the Internet and search engines. If you have a question about something, you type it in. Out pops (what you believe is) the correct answer, courtesy of your magical answer machine.

Things have changed since Leonardo’s time, you say. These days we have instant answers to every question; we don’t really need to be curious. There’s no point in it.

When I hear that, my curious mind can only ask: Really? Why? How do you know?

I advise you, as a writer, to reclaim some of your childhood curiosity, for two reasons.

First, we do not yet live in an age with all questions answered. Every day, someone uncovers facts that overturn a thing that “everybody knows.” Take any single thing you can name, anything, and decide to become an expert in it. Explore it, study it, read source material, visit the sites. You’ll soon explode a myth or two about your chosen subject; you’ll shift a paradigm; you’ll find out that what everybody knows just ain’t so. Despite what it says on the Internet.

Far from having all questions answered, we still live in humanity’s infancy. We are ignorant—monumentally, staggeringly ignorant. Worse, we don’t know how much we don’t know, and we truly know a lot less than we think we know.

The other reason I advise you to reinvigorate your curiosity is that it is precisely the questions that authors are really exploring in fiction—the deeper, thematic ones—for which the answers remain most elusive. How do I live a good and worthwhile life? Why am I here? What does it mean to be human? What is the nature of love?

If you aspire to write great fiction, think like Leonardo da Vinci. Embrace Curiosità. Ask questions. Many, many questions.

But there is no need to question the wisdom of—

Poseidon’s Scribe