In a 1920 essay, author Herman Hesse postulated there are three types of readers. Perhaps they’re more like stages of reading styles, since a person develops them sequentially. Or perhaps they’re more like modes, since a person will often switch between them. Let’s examine each one.

Reader 1

Hesse called this the naïve type. Here the reader follows the book, accepting every word without critical analysis. There is only the book and the reader, no author. The book stands above the reader in a hierarchy—the book leads, the reader follows. We all start out reading in this way, but often revert back to this method in later life.

Reader 2

A reader of this type is aware of the book’s author. This reader by turns loves or hates aspects of the book, and by extension, praises or blames its author. Hesse considered this reader both critic and interpreter, for this reader judges and creates meaning from the book’s text. This reader faces the book (and author) on the same level, in a hunter-prey relationship, with reader as hunter. Although you may call this a stage of reading, a level more advanced than Reader 1, it is also a mode, to which a reader can return at any time.

Reader 3

For this reader, a book serves only as a jumping-off point. Meanings, associations, connections, and fanciful interpretations arise in the mind, inspired by a paragraph, a sentence, a word, or the small arc capping the letter ‘r.’ A reader of this type thus transcends both book and author, leaving them beneath and behind. This reader needs no books at all, and finds them all equivalent. Of what use is a book when you can grasp eternal and infinite truths from the words on a gum wrapper?

Maria Popova provides a more in-depth description of these types in this post.

I’m indebted to Davood Gozli for his Youtube video where he expresses the three types in the vertical hierarchy I mentioned above.

Hannah Byrd Little, in this post, laments the decline of reading in our age of cellphones and social media. She believes young people today too often linger in the Type 3 Reader mode, with tweets and texts constituting the bulk of their reading matter, and serving only as springboards for connecting with online followers. The decline of reading deserves its own blogpost, and I’ll leave that for the future.

If we accept Hesse’s three-mode system, the question is, do you move from mode to mode, as he imagines most people do? If so, what percentage of time do you spend reading in each mode, and does that percentage vary by the subject matter you’re reading?

I’d estimate I spend about 20% of the time as Reader 1, absorbed by the book, oblivious to the world, willing to go where the book takes me. About 80% of the time I’m Reader 2, thinking critically about what I read. Maybe 2% of the time I enter Reader 3 mode, and then most often with poetry. I suspect the 4-to-1 ratio of time between Reader 2 and Reader 1 is consistent whether I’m reading fiction or non-fiction.

How about you? Do you accept Hesse’s classification of reading modes? Do you cycle between modes and, if so, what fraction of time do you spend in each mode?

I’m guessing you remained in Reader mode 2 while going through this post by—

Poseidon’s Scribe

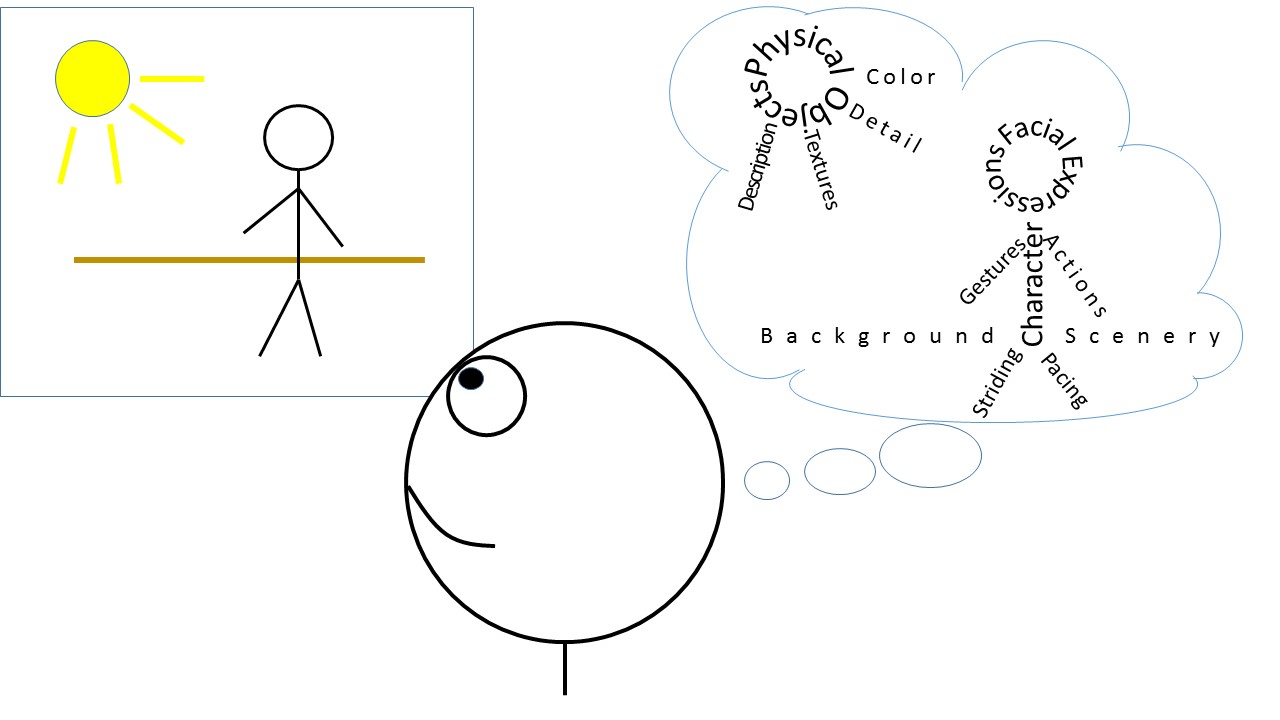

Before we get to writers, let’s discuss observation in general. While acknowledging there are other epistemological theories, I’ll assume there is a single, physical world out there, and each person observes it differently. Those differences are due to observations taken from different physical locations, accuracy of senses, mood, previous experiences, and many other things.

Before we get to writers, let’s discuss observation in general. While acknowledging there are other epistemological theories, I’ll assume there is a single, physical world out there, and each person observes it differently. Those differences are due to observations taken from different physical locations, accuracy of senses, mood, previous experiences, and many other things.