If you, Hopeful Writer, wish to astonish the world with a fictional character whom readers can’t forget, read this post by author Anne R. Allen.

I’ll repeat some of her major points here and add a few of my own. But my post serves only as a supplement to hers, not a substitute.

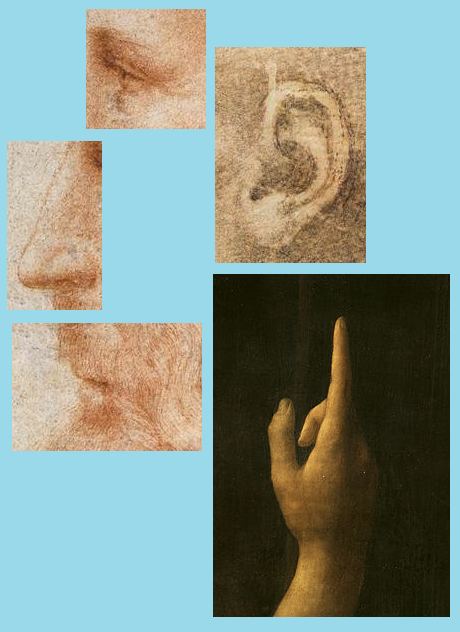

She advocates creating your character through the judicious use of details—the right details. Choose details both telling and distinctive. As when describing any object or place in words, make as much use of the five senses as is prudent, and add those qualities undetectable by any of those five. In describing characters, the predominant senses you’ll use are sight, hearing, smell, and possibly touch.

Senses

Start with the sense you’d like to emphasize most. We’re visual creatures, but you need not start with sight.

Still, let’s start there. In describing a character’s appearance, Ms. Allen’s post focuses on clothing, though body shape and dimensions also may deserve mention. Makeup, grooming, hair style, facial expression, even characteristic poses or hand gestures and nervous habits or tics come into play. The gait or manner of movement might also bear mentioning.

What distinctive noises can a character make? The speaking voice comes first to mind, but don’t limit yourself to tone or register, but also consider characteristic phrases, dialect, and speech mannerisms. Other parts of your character can also make noise, from the rustling of clothing fabric to the clomping of a cane or the tapping of shoe heels.

You might mention a person’s odor, whether pleasant or not. It can result from the body itself, perfume, clothing, an accompanying dog, etc.

On occasion, you might try the sense of touch—how a character feels on contact. Even if you don’t show another character touching the one you’re describing, you can suggest the potential for that action in another character’s mind. Perhaps the skin appears rough, or smooth, or certain articles of clothing might be of corduroy or silk.

Intangibles

How about those characteristics lying beyond the normal senses? In her post, Allen suggests mentioning the character’s music playlist. But such intangibles might include preferred food and drink, occupation, hobbies, habits, etc. Does the character possess some psychic connection to someone or something else? These things can help define and identify a character, but can’t be sensed.

Creation Process

Given the infinite number of choices, how do you select the right ones for your character? Allen mentions, and links to, several websites that might provide suggestions. I prefer to start by brainstorming. I imagine dozens of possibilities until a multi-sensory vision of my character emerges in my mind. I write ideas as I go, crossing out the ones that don’t work. While doing this, I do the sort of website research Ms. Allen advises. In time, I have a final description I can use.

You might not use every attribute you created, but use the ones most distinctive and telling, the ones that best convey your character’s essence. Old-style fiction writers used to lump all aspects of a character together in one batch, whether a paragraph or several pages. The modern method is to provide a few details at the first mention of a character, and sprinkle in other attributes later.

As the story proceeds, look for subtle ways to remind readers about your character’s description. Don’t overdo it, and don’t use the same words to describe a given attribute each time.

One clever technique is to change one or more attributes (or just the tone with which you describe it) as the story progresses. This change becomes a metaphor to suggest the way the character changes as a result of events in the story.

One cautionary note about character descriptions—make every effort to avoid stereotypes, tropes, and cliched characters. Here’s a way to detour around that pitfall—start with a stereotypical character, but add a clashing incongruity, a contradictory twist. Real people are complex, and you can make your characters complex, too.

Perhaps you’ll create your own famous and beloved character by following the advice of Anne R. Allen and—

Poseidon’s Scribe

Since that description is rather subjective, I prefer the simpler version provided by

Since that description is rather subjective, I prefer the simpler version provided by

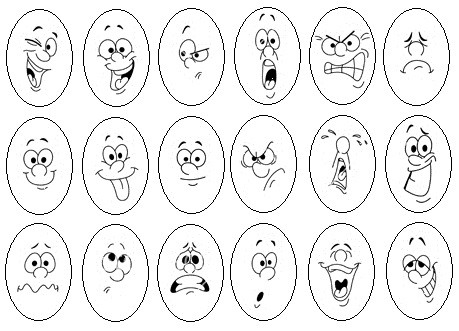

It’s important for a fiction writer to learn how to describe human facial expressions. A person’s face is the most communicative body area, and often it reveals a character’s feelings. Amazing, isn’t it, how many things we can make our faces do! There may be as many facial aspects as there are possible mental states.

It’s important for a fiction writer to learn how to describe human facial expressions. A person’s face is the most communicative body area, and often it reveals a character’s feelings. Amazing, isn’t it, how many things we can make our faces do! There may be as many facial aspects as there are possible mental states.