In his book The Way the Future Was, the late science fiction author Frederik Pohl stated, “Writing is not a spectator sport.” Oh, yeah? I set out to prove him wrong.

I rented a football stadium, hired two commentators, and advertised for several thousand of my fans to watch me write. Here’s the transcript, as broadcast:

Pat: “It’s a beautiful afternoon here at the stadium and we’ve got quite a crowd for this amazing event. Wouldn’t you say so, John?”

Pat: “It’s a beautiful afternoon here at the stadium and we’ve got quite a crowd for this amazing event. Wouldn’t you say so, John?”

John: “No doubt about that, Pat, weather-wise and crowd-size-wise. But this is the first time I’ve covered one of these writer athletes, and I’m not sure what to expect.”

Pat: “It’s a first for both of us. Look, the writer himself has entered the field and is making his way to the center, and the crowd’s cheering.”

John: “I like his confidence. You can see it in his walk. He’s not swaggering or strutting, just striding with confidence. I like that.”

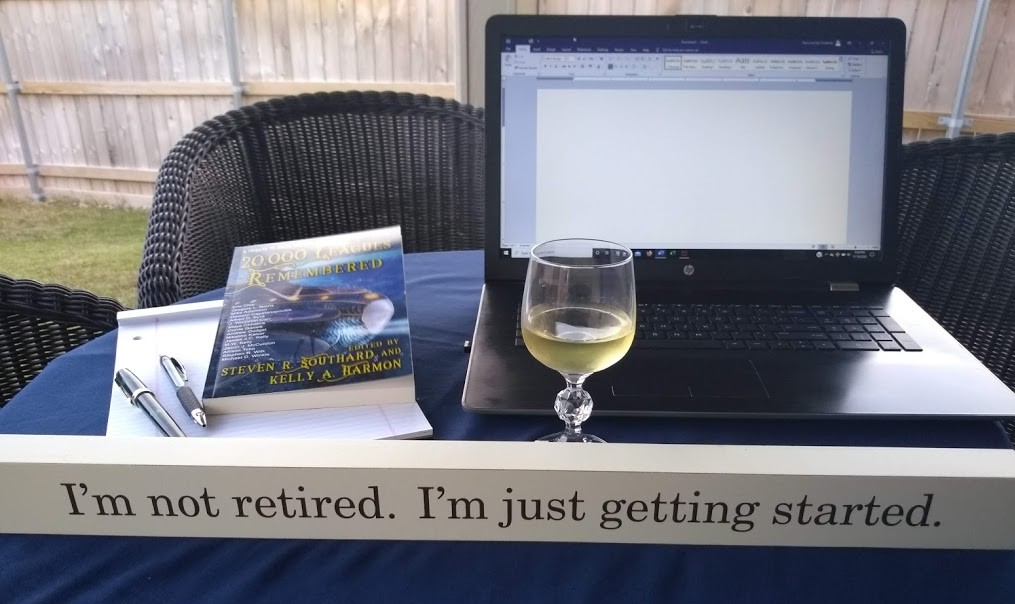

Pat: “Tonight’s writer is Steven R. Southard. He’s been writing for several seasons already, and his career is on an upswing. He’s reached midfield now and is sitting at the desk there. The crowd is settling down. I’m guessing things will start soon.”

John: “I’m a bit confused, Pat. There’s no team with him. No opposing team out there, either. Not a single referee, and no coaches pacing the sidelines.”

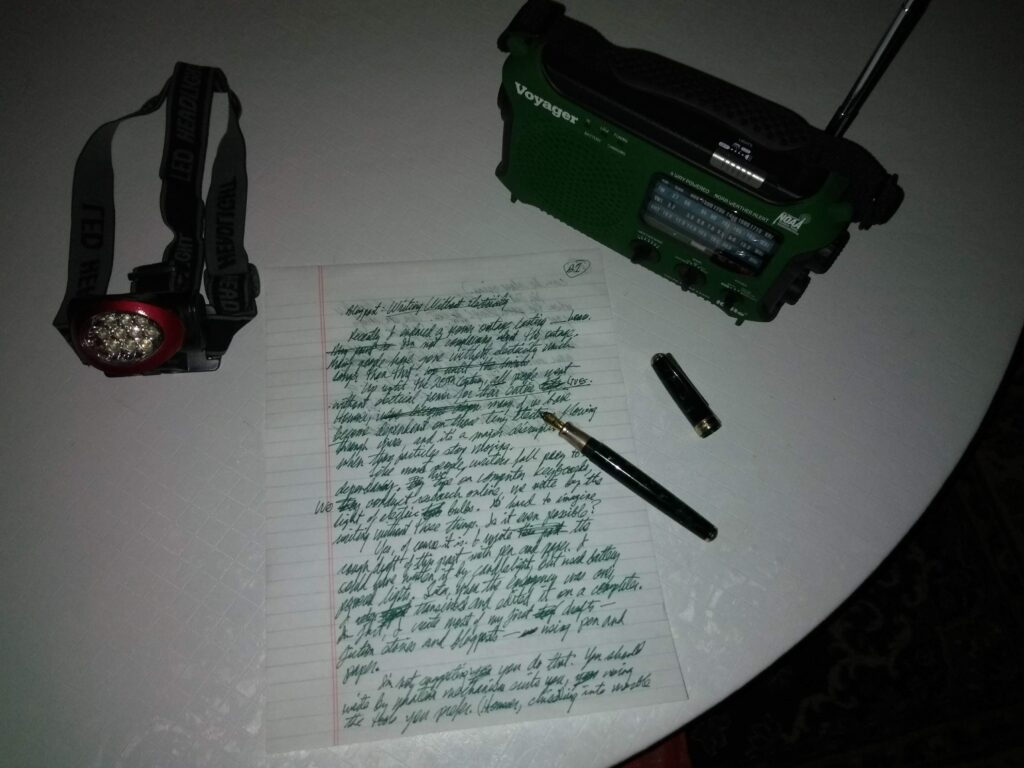

Pat: “I guess that’s the way writing is, John. Must be a solitary thing. Look, Steve has turned on his computer. The stadium scoreboard is off so I don’t know if time has started or not.”

John: “I think we must have a second-rate writer, here, Pat. This guy is just staring into space. He hasn’t typed a thing. Now he’s sipping some coffee. I sorta expected more action, typing-wise.”

Pat: “Maybe fiction writing isn’t all typing. Apparently there is some amount of thinking involved, too.”

John: “If he keeps this up, he’s going to be traded in the off-season. This is just the kind of lazy work ethic that…hold on. He’s typing on the keyboard now. He’s actually typing.”

Pat: “True, John, he is. We can’t see the words from here. We’ll see if we can get a close-up view. He’s definitely pounding out some prose.”

John: “And the crowd’s getting into it, too. They can sense the energy. Still, he might want to work on his posture, because—uh, oh. He stopped. Did he call for a timeout? We’re back to that staring-into-space play that didn’t work before. How many timeouts do they allow in this sport?”

Pat: “I’m not sure, but we’re going to cut to a commercial break. Don’t change the channel, folks. There’s more exciting action coming up.”

——————————————————–

Pat: “We’re back, live at the stadium. There was some activity during the break.”

John: (odd sound, possibly yawning) “Yeah, but it was the wrong kinda action, Pat. No typing at all. Southard got up from his chair and paced around the desk a few times, gesturing and talking to himself. He’s not going to get any stories written that way.”

Pat: “He sure isn’t. A lot of fans seem to agree too, and are leaving for the parking lot. It’s hard to know if our writer is making any progress down there on the field.”

John: “Progress? He hardly moves. I can’t stand this anymore. This isn’t a sport! The boredom is killing me. I’d rather watch goalposts rust, or wait for Astroturf to grow. I’m leaving.”

Pat: “We’ve only been here fifteen minutes, John.”

John: “Then why do I feel fifteen years older, age-wise?”

The broadcast ended soon after that when both commentators and all the camera operators left. Perhaps Frederik Pohl was right after all, um, correctness-wise. From now on, writing will return to being a non-spectator event for—

Poseidon’s Scribe

Sitting at your computer, you produce your first work product of the day. (What’s the product? I don’t know; we’re talking about your current day job.) You e-mail it to your boss and wait. A few hours later, your boss e-mails you back to say the product didn’t suit her needs. She says she can’t accept it.

Sitting at your computer, you produce your first work product of the day. (What’s the product? I don’t know; we’re talking about your current day job.) You e-mail it to your boss and wait. A few hours later, your boss e-mails you back to say the product didn’t suit her needs. She says she can’t accept it.

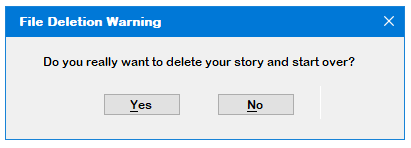

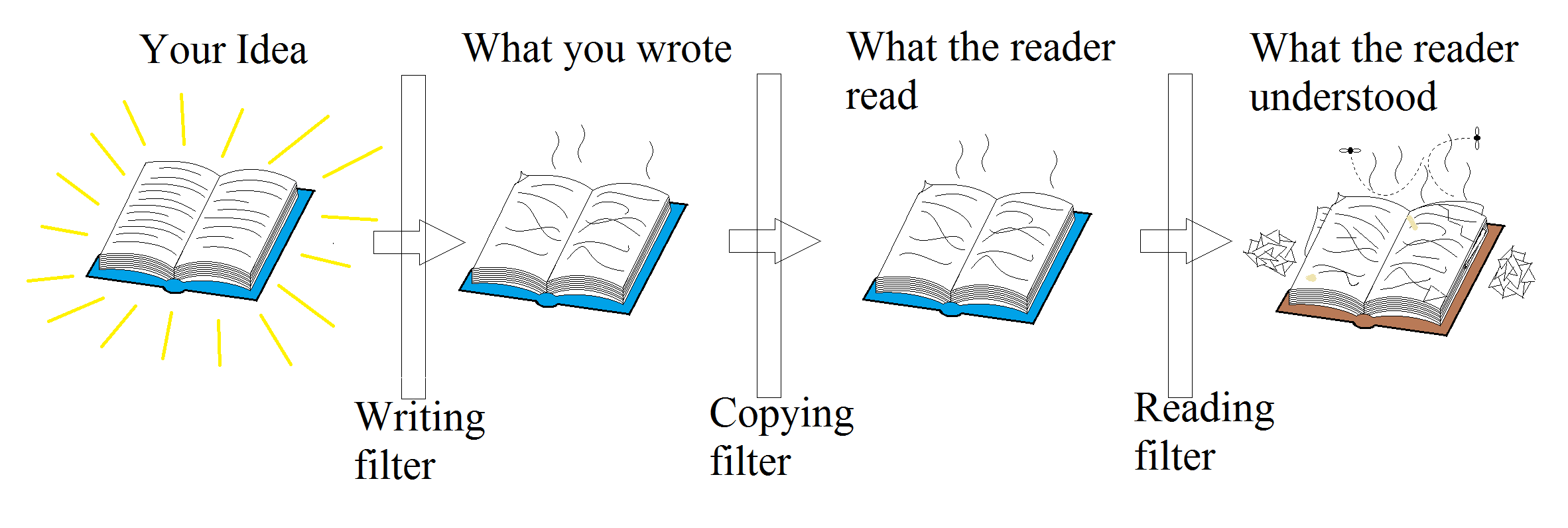

The process is usually not as bad as the way I’ve dramatized it in the accompanying image. Still, it’s a less efficient transmission method than mental telepathy would likely be.

The process is usually not as bad as the way I’ve dramatized it in the accompanying image. Still, it’s a less efficient transmission method than mental telepathy would likely be.

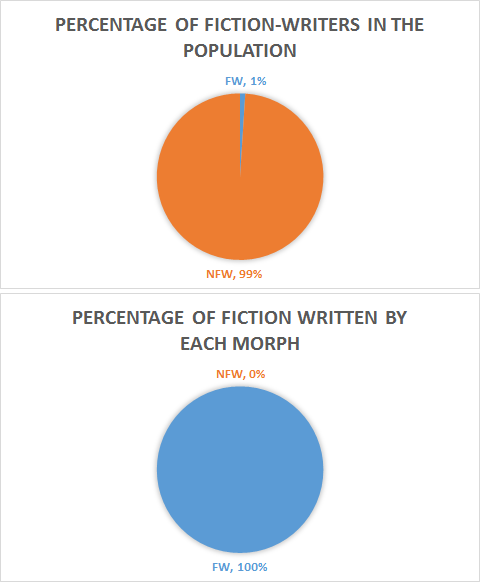

Observations indicate the vast majority (greater than 99 percent) of adults within this species do not write fiction. The fiction-writing and non-fiction-writing fractions have not split off as separate species, and seem unlikely to do so. The distinction between the two is behavioral only, so we may define the fiction-writers as the FW Morph, and the others as the NFW Morph. Other sub-species terms such as breed, race, cultivar, ecotype, and strain are not as applicable as morph.

Observations indicate the vast majority (greater than 99 percent) of adults within this species do not write fiction. The fiction-writing and non-fiction-writing fractions have not split off as separate species, and seem unlikely to do so. The distinction between the two is behavioral only, so we may define the fiction-writers as the FW Morph, and the others as the NFW Morph. Other sub-species terms such as breed, race, cultivar, ecotype, and strain are not as applicable as morph. In an economic sense, it is fortunate that FWs are in the minority; otherwise they would have to pay NFWs to read their books, rather than the other way around.

In an economic sense, it is fortunate that FWs are in the minority; otherwise they would have to pay NFWs to read their books, rather than the other way around.