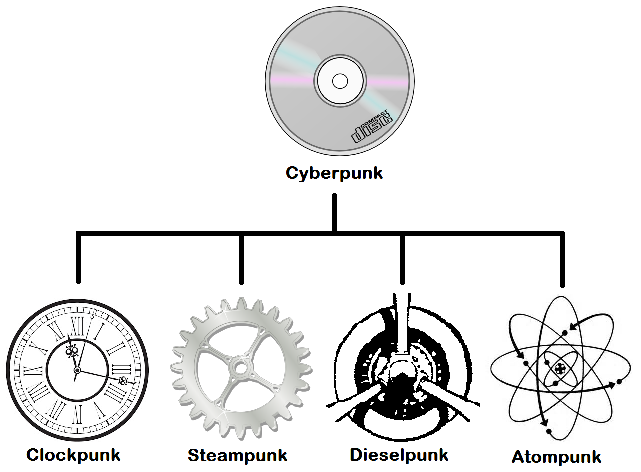

Fresh out of story ideas? Try the 1G Nostalgia Formula. (My name for it. Trademark application pending.)

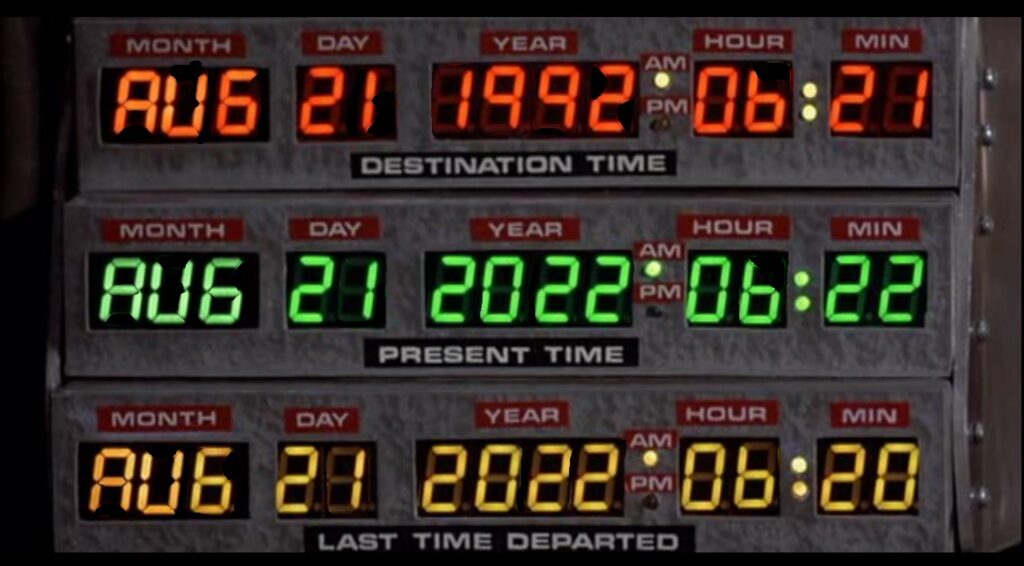

Here’s how the 1G Nostalgia Formula works. Take today’s date and subtract twenty-five to thirty years (about one human generation), and set your story in that time period.

As you do this, research as much as you can about that era—clothes, catch phrases, news, culture, sports, songs, movies, etc.

Why do readers find such stories appealing? For the young, it’s a chance to satisfy their curiosity about their parents’ time, and to feel a little smug about those “simpler times.” For older readers, such stories trigger memories, not of simpler times, but of their younger and simpler selves. “Yeah, I remember that.”

The TV industry glommed onto this formula decades ago. Consider “M*A*S*H,” “Happy Days,” “That ‘70s Show,” “Mad Men,” and others, all set in earlier eras.

You needn’t be precise about the one-generation part of the formula. Pick a time period within living memory of at least some of your target audience. One generation works well, since you’re maximizing the size of that audience.

The formula hinges on how well you immerse your readers in that time period, and how many contrasts you can draw between that time and the present.

In creating the feel of your time setting, it’s okay to exaggerate a little. Say you’ve picked the mid-1990s for your story’s time period. Feel free to make your story even more mid-90s than the real mid-90s were.

This requires simplifying the complicated, clarifying the vague, and concentrating the diffuse. Complexity characterizes every era. No time period separates itself by damming off the flow from earlier, or the flow to later, times. Currents and counter-currents form eddies and whirls in the river of time.

William Gibson said, “The future is already here—it’s just not evenly distributed.” That uneven distribution also applies to the past time period you choose for your story.

Depending on the needs and purposes of your tale, you may not wish to depict these complexities, at least not at first. Best to give your readers a unified, integral gestalt—an exaggerated mid-90’s, for example, free of any lingering 80’s remnants, and free of millennial foreshadowings. If the story might benefit from those slight anachronisms, introduce them later.

These can take the form of a grandparent character who can only relate to an even earlier time (2G). Or it can be a forward-looking character, perhaps a science fiction fan, who imagines a future much like our own present. These aspects can add delightful cross-currents to liven up a nostalgic story.

None of this advice takes the place of the writer’s prime directive: write a good story. Just because your tale follows the 1G Nostalgia Formula, that doesn’t guarantee sales. The subject matter might pique reader interest, but you only gain buyers and readers by writing well.

Ready to set your creative time machine to a date one generation in the past? All you have to do is hit the gas. Your destination switches have already been set by—

Poseidon’s Scribe