Judging from recent literature, the future looks bleak. The Hunger Games, Divergent, The Maze Runner, Delirium, Matched, Legend, and others paint visions of worlds much worse than our own.

Without question, these books sell well. Some have become movies. We readers have a fascination with dismal futures, possibly because:

- They make our own present seem better by comparison;

- We like to imagine the end result of current downward trends;

- The character’s stakes are high, the conflicts larger than life;

- We identify with being a victim of society;

- It’s inspiring to read about characters making the best of things in the worst of places; or

- Millennials, raised in the shadow of 9-11, actually believe their future will be worse than their present.

From the writer’s point of view, dystopias have this advantage—at least one of the book’s conflicts is baked in from the start. There will be some sort of man vs. society conflict going on. Whatever other conflicts are present, you’ll find a struggle between the individual and the state. By contrast, in utopias, conflict is harder to come by.

From the writer’s point of view, dystopias have this advantage—at least one of the book’s conflicts is baked in from the start. There will be some sort of man vs. society conflict going on. Whatever other conflicts are present, you’ll find a struggle between the individual and the state. By contrast, in utopias, conflict is harder to come by.

For this post, I’ll define utopian literature to refer to fiction set in a future world that’s better and more technologically advanced than our own, but is not necessarily a perfect world. Dystopian literature is fiction set in a future world worse than our own (with either more advanced or less advanced technology), it’s but not necessarily a completely hellish world.

Utopian literature doesn’t seem to be selling as well as its dystopian opposite. Such books once rocketed off shelves. Almost all science fiction written in the 1940s, 50s, and 60s assumed society and technology would advance and life in general would improve.

Utopian literature doesn’t seem to be selling as well as its dystopian opposite. Such books once rocketed off shelves. Almost all science fiction written in the 1940s, 50s, and 60s assumed society and technology would advance and life in general would improve.

Such utopian books didn’t portray perfect futures. The characters suffered from problems and challenges as dire as those in any novel. After all, if someone traveled to our present from almost any period in the past, they’d view our modern era as utopian, thanks to our long life spans, medical advancements, reasonably plentiful food, and readily available technology. We look around us and see no end of problems, but in the eyes of our ancestors, we all inhabit Utopia.

Does the prevailing literary mood reflect society’s predominant attitude toward technology? In the 1940-1970 period, could it be that the Space Race, combined with the baby boom (which produced a huge number of youthful readers), result in a yearning for optimistic literature?

Might it be that today’s readers no longer hold a positive view of technology? Has the rise of terrorism, increasing surveillance, climate change, cybercrime, and a fear of artificial intelligence biased the current book-buying public against science?

Possibly, but Baby Boomers had “bad” technology, too—namely, the Bomb. And Millennials have plenty to be optimistic about, such as driverless cars, household robots, 3D printing, hyperloops, missions to Mars, etc.

If each generation knew both good and bad technology, then why would they hold such different attitudes toward it? Or is it something besides a prevailing view of science?

Could it be all due to the Boomers alone? Maybe that “pig in a python” generation is, all by itself, influencing literature as its population ages. That is, when Boomers were young and optimistic, they preferred Utopia, but as they became older, sadder, and wiser, they pulled up stakes and moved to Dystopia.

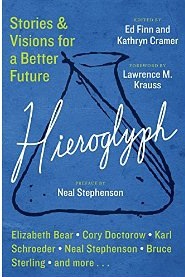

Whatever the reason for the current literary preference, some evidence indicates the reaction against dystopia and back toward utopia has begun. In 2011, author Neal Stephenson helped found Project Hieroglyph which seeks fiction and nonfiction depicting a positive future. The published anthology, Hieroglyph, is on my list of books to read.

Whatever the reason for the current literary preference, some evidence indicates the reaction against dystopia and back toward utopia has begun. In 2011, author Neal Stephenson helped found Project Hieroglyph which seeks fiction and nonfiction depicting a positive future. The published anthology, Hieroglyph, is on my list of books to read.

I prefer utopian fiction. Being a techno-optimist, I prefer to think the future will be better than the present, and reading such books keeps me in that mindset. However, I’m not Pollyannaish; I know society could well backslide, much as the thousand year Dark Ages followed the Roman Empire. Further, I know readers of dystopian books don’t necessarily believe the future of the real world will be dismal.

Let me know your position on this spectrum. Do you read solely utopian, or solely dystopian books? Or perhaps you don’t care, so long as the book is good. Your comment may influence the type of fiction to be written by—

Poseidon’s Scribe