What are the things you should be thinking about before you write a scene in your story? Pantzers and Plotters will approach this question differently in the first draft, but in subsequent drafts, the questions will be the same.

Whether your work is a novel or short story, it is a sequence of scenes. A novel’s chapter can have one or more scenes, as can a ‘part’ or ‘section’ of a short story.

I’ll look at two approaches today, and you can combine them or pick the one you like. When I researched the topic, I found an approach used by Larry Brooks and a different one used by Dr. Randy Ingermanson. I’ve mentioned Ingermanson before in connection with his snowflake method of writing.

Larry Brooks’ View

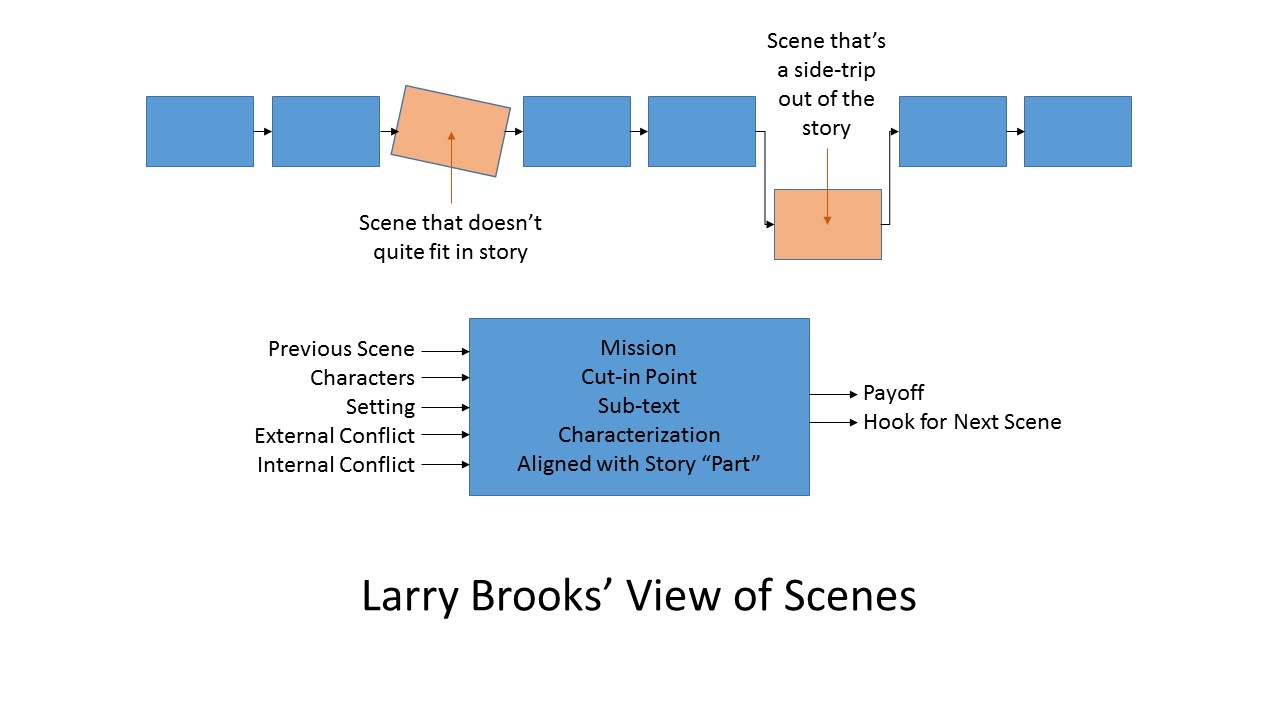

My picture of Larry Brooks’ method shows the story as a sequence of scenes. If written well, each scene serves an important purpose in the story. If written poorly, a scene can seem out of joint, or even seem like a side-trip out of the story.

I’ve drawn a single scene as a system with inputs and outputs, but Brooks hammers home the importance of having a mission for the scene, a mission that advances the plot somehow. The scene’s mission must also support the overall strategy for the story.

I’ve drawn a single scene as a system with inputs and outputs, but Brooks hammers home the importance of having a mission for the scene, a mission that advances the plot somehow. The scene’s mission must also support the overall strategy for the story.

He discusses ways to choose the point to start the scene—the cut-in point. He suggests you think about sub-text to put in the scene, those unstated inferences that show the reader a character’s true thoughts, or make some metaphorical thematic point. Brooks says that all scenes should develop or reveal characters, but that should never be the sole point of the scene.

In Brooks’ view, a writer must align every scene with one of the four parts of a story. These parts are the Set-Up, the Responder, (where the protagonist is responding to the First Plot Point), the Warrior (where the protagonist grapples with the main conflict), and the Resolution.

Lastly, the scene has to end in a way that urges the reader on.

Randy Ingermanson’s View

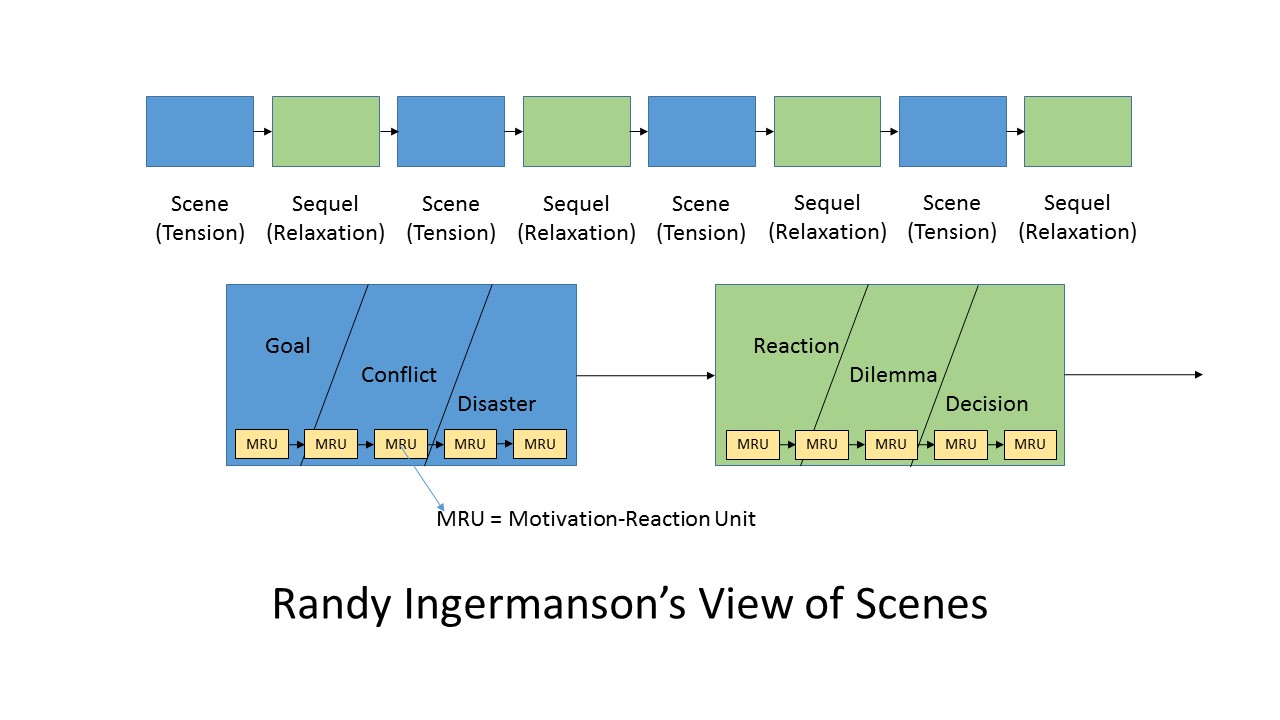

Randy Ingermanson takes a more structural and prescriptive approach. He encourages writers to view scenes at a Large Scale and a Small Scale. In discussing the large scale view, he uses terminology from Dwight Swain and suggests that all scenes are either scenes or sequels. (I prefer to use the terms tension and relaxation.) These alternate in sequence, to allow the reader to catch a breath between points of high drama or action.

The tension (scene) scenes each include a goal, a conflict, and a disaster. The relaxation (sequel) scenes each include a reaction, a dilemma, and a decision. That sets the write up for the next tension scene.

The tension (scene) scenes each include a goal, a conflict, and a disaster. The relaxation (sequel) scenes each include a reaction, a dilemma, and a decision. That sets the write up for the next tension scene.

Turning to the small scale, Ingermanson says good writers construct each scene from a series of MRUs – Motivation-Reaction Units. The motivation is some external happening sensed by the point-of-view character. The reaction is the internal emotions or thoughts experienced by the POV character as a result.

Final Thoughts

I’ve condensed the thoughts of both Brooks and Ingermanson, and I encourage you to read each of their full posts. There is much to learn from both views, and they are not contradictory, so it’s possible to do both.

If you consider their approaches before and during your first drafts of any scene, and during the rewriting and editing of subsequent drafts, I’m betting your stories will be more focused, more readable, and more enjoyable.

Time to split this scene and return to the other never-ending duties of—

Poseidon’s Scribe