When you’re stuck for a story idea, it may seem like other authors have already written all the good tales. Every time you think of a plot, for example, your head swims with titles that have covered that plot, worn it thin.

Are there only so many plots, you wonder, peopled with different characters, set in different places and times, portraying different themes, and written in different tones and styles?

Others have wondered that before you, and developed their own lists of all plot types. Prepare to be confused, and then (perhaps) unconfused.

Others have wondered that before you, and developed their own lists of all plot types. Prepare to be confused, and then (perhaps) unconfused.

In his 2004 book, The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories, Christopher Booker declared there are seven plot types: Overcoming the Monster, The Quest, The Voyage and Return, Rags to Riches, Rebirth, Comedy, and Tragedy.

One year earlier, Ronald B. Tobias came out with his book, 20 Master Plots: And How to Build Them. His list included plots such as Revenge, Transformation, and Wretched Excess.

One year earlier, Ronald B. Tobias came out with his book, 20 Master Plots: And How to Build Them. His list included plots such as Revenge, Transformation, and Wretched Excess.

Much earlier, in 1916, the book The Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations by Georges Polti introduced thirty-six plot categories, including Obtaining, Rivalry of Superior and Inferior, and Loss of Loved Ones.

Much earlier, in 1916, the book The Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations by Georges Polti introduced thirty-six plot categories, including Obtaining, Rivalry of Superior and Inferior, and Loss of Loved Ones.

Great, you’re thinking, but how many are there—seven, twenty, or thirty-six? That depends on the way you like to categorize things. You could cut a pizza into seven, twenty, or thirty-six pieces, and they’d still add up to the same pie.

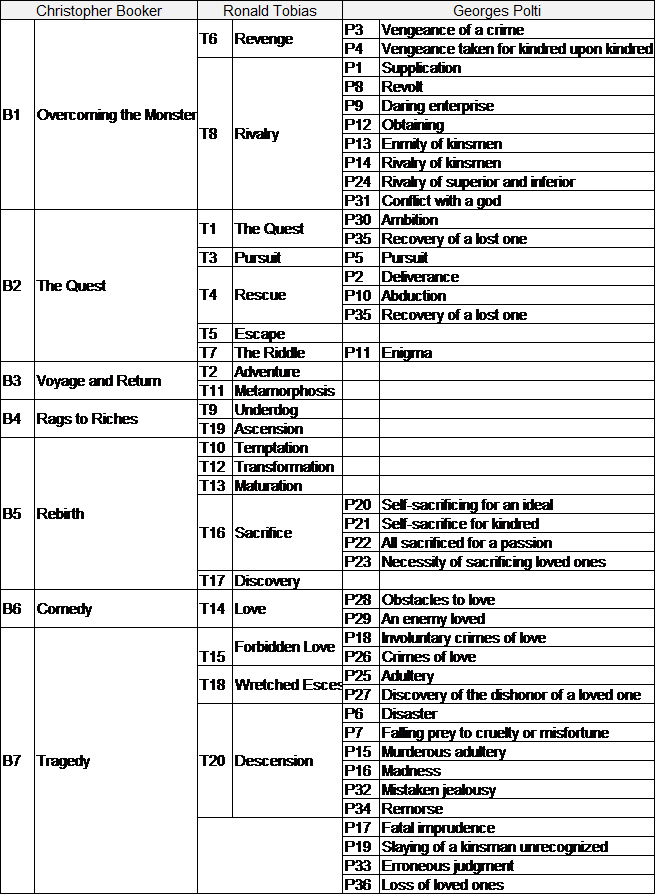

That’s what I wanted to explore today. How do those categorization schemes compare to each other? Can you take Booker’s seven plots and see where Tobias’ twenty fit into them? Do Polti’s thirty-six plots fit somehow with Tobias’ and Booker’s taxonomies?

I couldn’t find any example of someone doing this, so I did it. I designated each of Booker’s categories with a B-number: B1, B2, etc. I did similarly with Tobias’ 20 (T1, T2, etc.) and Polti’s 36 (P1, P2, etc.)

Then the trouble started. Many didn’t fit well at all. In such cases, I read the descriptions the authors gave for their categories and chose the one in the other’s categories that seemed most like the one I was considering. You may disagree with the way I’ve mapped them, and I’d love to know your reasoning.

For your careful study, wry amusement, and utter disgust, here is my mapping of the three plot schema against each other:

By now, some questions have occurred to you. One might be, “Can’t a single story be a mixture of two or more of those plot types?” Answer: Yes, there’s no law against that.

Others of you are asking, “Why are the love stories listed as comedies?” Answer: Booker defined his comedy category as including more than humorous stories, and in particular included love stories in that group.

Lastly, there are those asking, “Of what use is this map? Come to think of it, of what use are the three taxonomies?” Answer: for those who asked that, I have no answer that will satisfy you. Go ahead and just write any old story whether it fits a pre-discovered plot category or not.

For those who didn’t ask that last question, you’re probably comfortable with the fact that some people like to take a mass of data and try to organize it somehow, to create filing categories like a Dewey decimal system or biological taxonomies.

Whether you think there are seven, twenty, or thirty-six plot types, or if you don’t see the point in dividing that pizza at all, there are plenty of stories remaining for you to write. Let’s see if the next one you create will be better than any authored by—

Poseidon’s Scribe