Ask a chatbot to write a story and it will do so. You’ll find the result contains the correct story elements. However, if you do that today, the story won’t move you. You’d rate it at junior high school level, certainly not a classic.

That describes the state of artificial intelligence story-writing in mid-2024. From this, you might well conclude that AI will never write stories as well as the best human authors do.

Prediction

Indeed, author Fiona M. Jones is the latest to draw that conclusion. She asks “is there any realistic prospect of AI ‘improving’ to a point where it becomes indistinguishable from the work of creative writers? Maybe you can imagine it. I can’t.” She goes on to state “I am not afraid that AI bots will take my place as a writer.”

I intend no disrespect to Ms. Jones. Others share her opinion. I accept the possibility that her contention may prove correct.

Superiority Complex

However, it occurs to me that the history of our species includes several symptoms of a shared superiority complex. In each case, people erected a metaphorical pedestal for humanity, only to have science tear it down.

- In cosmology, early depictions of the universe showed Earth at the center. Today, astronomers relegate our world to a backwater.

- In zoology, humans have long regarded themselves as lords of the animal kingdom. We claimed to possess the largest brain, and to be the only creature that feels pain or happiness, that talks, that uses tools, that is self-aware. The march of science seems to be trampling this pedestal as well.

Story-writing Today

For now, humans stand, undisputed, atop the Best Story-writers pedestal, at least on this planet. We’ve stood there for thousands of years, so it seems natural to regard the honor as permanent.

At this moment, AI seems unlikely to unseat us from that perch. In that, I agree with Fiona M. Jones. We humans have written stories for thousands of years, and told them verbally far longer than that. AI chatbots have written stories for a much shorter time, a few years at best. Hardly a fair comparison.

AI chatbots learn fast. Very fast. They can memorize the entire internet. They do not die, and therefore don’t have to teach the next generation of chatbots to write. I expect them to write with more skill and originality soon. But could they surpass us?

Ms. Jones offers many good arguments, but they boil down to the fact that human authors write about the human condition, and chatbots can’t possibly understand the human condition as well as humans do.

Maybe. But consider that human fiction writers often convey the thoughts and emotions of non-human characters in their stories. These characters include gods, animals, plants, even inanimate objects. Given similar creativity and imagination, chatbots might become capable of conveying human thoughts and emotions in a convincing way, even though they’re not human.

Story-writing Tomorrow

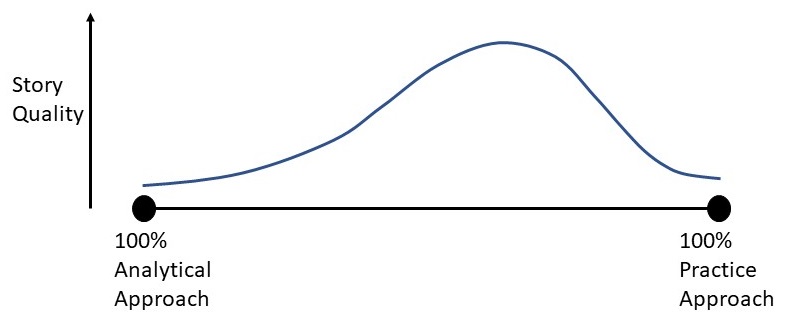

You could measure a story’s quality by the intensity of emotion it produces in the reader. Once AI chatbots understand us better, what’s to prevent them from crafting stories evoking strong emotions?

When and if they do, what will that mean for human readers? For human writers? I’ve already explored some of these implications in a previous blogpost and won’t repeat them here.

I suggest we should not assume our present superiority will last. We may not remain forever at the center of the writing universe, at the pinnacle of writing prowess, standing atop the Best Story-writer pedestal.

It should not surprise us when the first AI-written novel tops the Best-Seller list. Even then, we should not dismiss that achievement as a novelty, a fluke, unlikely to repeat.

In the meantime, fellow human writers, I suggest we write and publish the best stories we can, while they still sell. That’s the course steered by—

Poseidon’s Scribe