You hear the terms “writer” and “author,” but do you know the difference? Is there a difference?

Definitions

Writers are people who write. They write fiction, nonfiction, books, vignettes, emails, texts, letters, grocery lists—doesn’t matter. They may write for others, for themselves or for nobody—doesn’t matter.

Authors are people who’ve had writing published. Big press, small press, self-published—doesn’t matter. Their work gets read by others and is intended that way.

Relationship

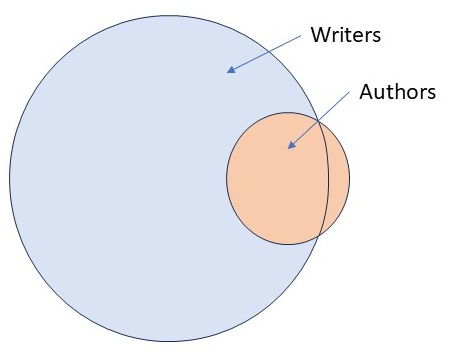

You may infer from those definitions that all authors are writers, but not vice versa. For the most part, that’s correct.

As shown in the Venn diagram, you may be an author without being a writer. That’s the case if you hire a ghost writer. As the author, your name appears on the book cover, but you didn’t write it.

No Certificate

No sanctioning body bestows the titles of writer or author. No authority bestows diplomas, sew-on patches, or military-style chest ribbons. You’re a writer if you say you are. You’re an author if you can point to a published work bearing your name.

Attitude

Definitions and certifications aside, a notable factor separates authors from writers, and I don’t see this discussed much. Attitude. Here, I’m contrasting authors with those writers who aspire to become published authors.

Not all writers seek publication, and that’s fine. Better for them, in some ways. No publisher will reject their manuscript. No critic will pan their book.

Many writers do pursue publication, though, and until they achieve it, you can tell a writer from an author by attitude alone.

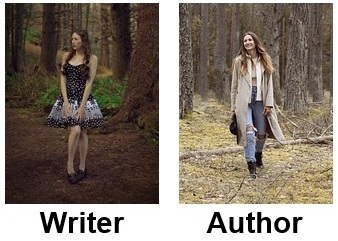

Writer Attitude

For writers, the path to publication seems daunting. They tread with care and hesitation through new territory, toward that glorious land of publication located beyond their zone of comfort. Though hopeful as they pursue a dream they glimpsed, they’re also fearful and they walk with tentative steps through a realm of mystery.

Author Attitude

Authors, even those with a single published short story, stride with a confident swagger, their chin up and their eyes glinting with determination. They’ve been down the trail before and know every rock and root, each bush and branch. They walk with a calm assurance borne of past experience.

Evidence

How do I know? When I go to scifi conferences, I see writers who dream of publication and I see authors who’ve achieved it. I witness a marked difference in gait, in bearing. Writers gaze at authors with awe, and authors carry themselves with poise and graceful ease, as if they own the world.

I saw this in my own journey. However, my authorial stride retains some writerly unease, and hasn’t reached full-fledged complacency yet. But there’s something about the assurance I felt from past accomplishment, knowing I could do it again.

You, Too

Take heart, writer. You’ll get there. One day you’ll walk (in the words of Shakespeare) “bestride the narrow world like a Colossus.” You’ll strut around like—

Poseidon’s Scribe