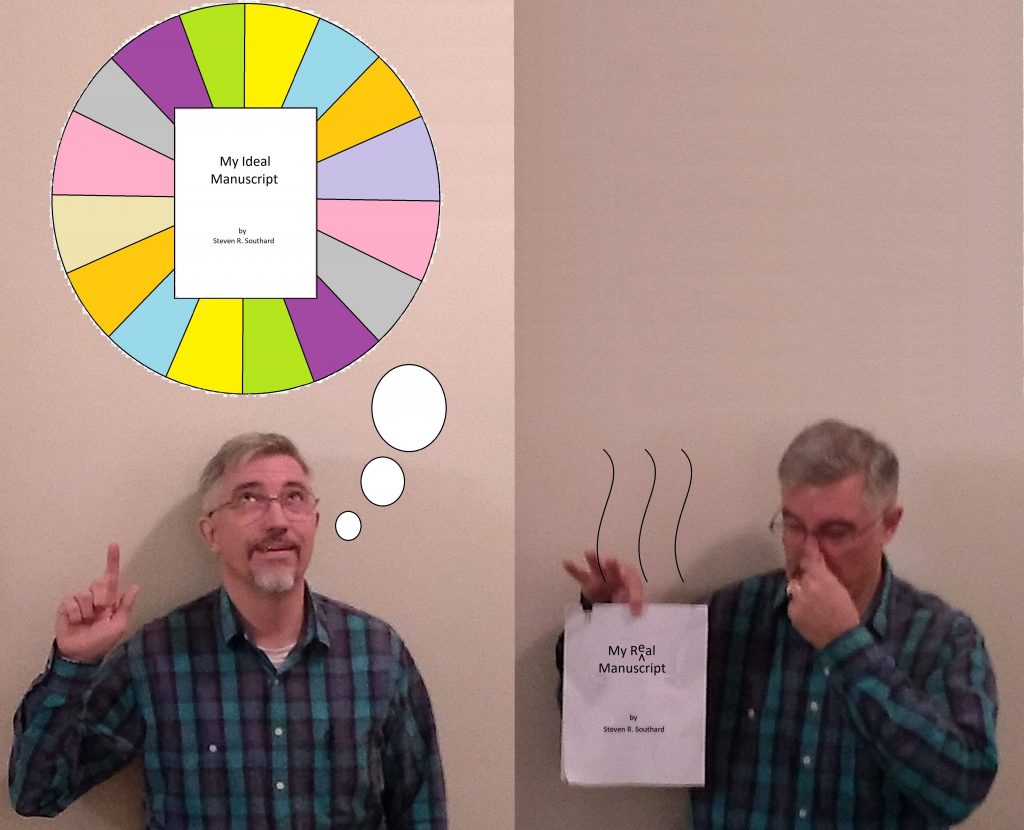

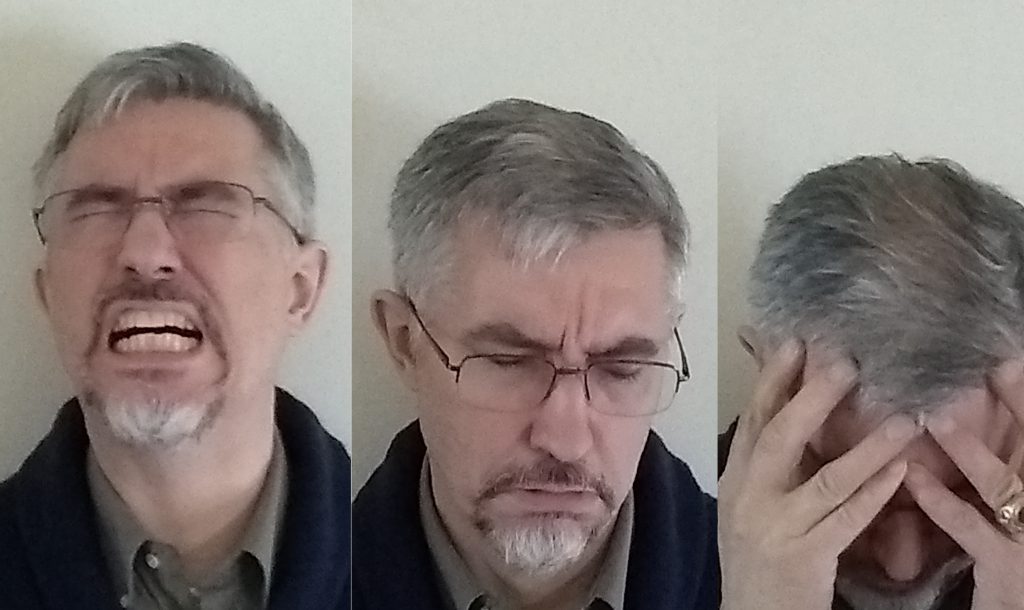

That story idea was so good, wasn’t it? While it remained an idea, it radiated beams of perfection across your mind. It screamed “Classic!”

Then you wrote it down. Now it doesn’t look so good. In fact, it stinks.

How could the same story that seemed so ideal when it sat upon a pedestal within your bran, end up so pathetic when you wrote it down?

Here are some reasons for that large ideal/real gap, and what to do about it:

- You only completed a first draft. There’s no reason to expect your first draft to be good. You wrote it in a rush, not wanting to lose sight of the broad outlines of the story idea in your mind.

Solution: Keep editing the story. In subsequent drafts, it will approach closer to the ideal version.

- The emotions faded. You felt some powerful emotions while thinking about the story. Somehow, during the writing process, those passions abated. Now the real manuscript lacks the fire of the mental one.

Solution: Put away the manuscript. Just think about the story again and try to recapture the feelings you had when you first thought of it. If you can do that, you may discover ways to improve the real version.

- You got sidetracked. While writing down your story, you thought of some new characters, or a different setting, or a new subplot or plot twist. Whichever it is, that marked a deviation from the ideal story residing in your mind.

Solution: You’ve got a decision to make. Does the deviation make the story worse, or better? If worse, delete it. If better, keep it.

- A character demanded a bigger role. Somehow, during the writing process, one of the characters started stealing the show. That character developed a deeper personality and started speaking unimagined lines and taking unforeseen actions.

Solution: As with the previous problem, you’re facing a decision. Think in terms of the story. Does this character’s expanded role improve the story or not? If so, keep that character as is. If not, you can either reduce the character’s part or substitute a different character. (Consider using that scene-stealing character in a different story.)

- That mental story only seemed ideal. You discovered some things while writing the story. That story idea contained some serious flaws, like plot holes, actions without motivations, unnecessarily complex solutions to problems, or loose ends. Sometimes an idea only seems good until it sees the light of day.

Solution: If you fixed the problem while writing the story, go with the one you wrote. If you got stuck partway through, shelve the story for a while. Someday, your muse may suggest a revised idea you can work with.

- Your ideal is unattainable in reality. That mental version of the story is so clear, so perfect, but you just can’t match it in the real manuscript. You’ve been through several drafts now, each one better than the last, but it still doesn’t quite measure up.

Solution: You can be like Leonardo da Vinci if you want, and dabble with your Mona Lisa for over a decade, making little improvements here and there. But consider declaring that story good enough and start writing another one.

We all struggle with the gap in quality between the ideals in our mind and the flawed reality of our tangible creations. It’s part of the human condition for our mental reach to exceed our physical grasp. Perhaps the Mona Lisa never matched da Vinci’s idea of her, but his painting still leaves most of us in awe.

Now that I read back over it, this blog post falls far short of the one imagined by—

Poseidon’s Scribe

For my purposes here, let’s consider insanity a rare condition. Let’s use the term as a psychologist might, and not like the hyperbole we use when seeing someone do something remarkable: “He’s insane!”

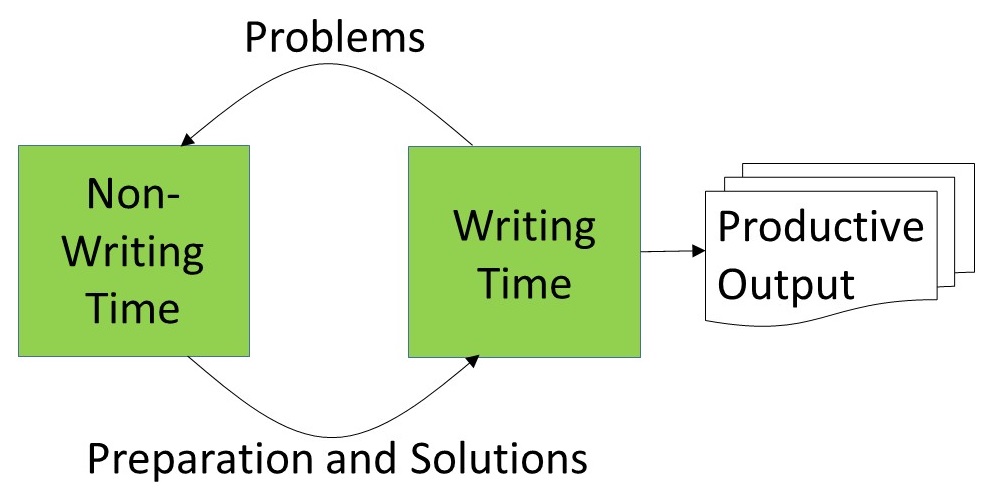

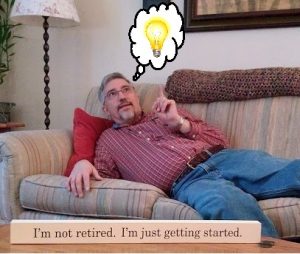

For my purposes here, let’s consider insanity a rare condition. Let’s use the term as a psychologist might, and not like the hyperbole we use when seeing someone do something remarkable: “He’s insane!” Let’s say you’d like to be a writer, or a more prolific writer. The trouble is time. There’s not enough of it in your day. The rest of life sucks up too much time. Just when you find yourself with a few free minutes to write, the words won’t flow, or you’re too exhausted.

Let’s say you’d like to be a writer, or a more prolific writer. The trouble is time. There’s not enough of it in your day. The rest of life sucks up too much time. Just when you find yourself with a few free minutes to write, the words won’t flow, or you’re too exhausted. By the way, this process of having your non-writing time influence your writing time—it also works the other way around, too. When you’re writing and you come across a problem, relax. You don’t have to solve it right away. Just file it away for future thought. That’s what your non-writing time is for. Simply move on. In this manner, your writing time also serves to prime the pump with problems to work on in your non-writing time.

By the way, this process of having your non-writing time influence your writing time—it also works the other way around, too. When you’re writing and you come across a problem, relax. You don’t have to solve it right away. Just file it away for future thought. That’s what your non-writing time is for. Simply move on. In this manner, your writing time also serves to prime the pump with problems to work on in your non-writing time. Your muse, like all of them, isn’t the most focused entity around. Easily distracted by new and shiny objects, she comes up with fresh ideas all the time.

Your muse, like all of them, isn’t the most focused entity around. Easily distracted by new and shiny objects, she comes up with fresh ideas all the time.

Sitting at your computer, you produce your first work product of the day. (What’s the product? I don’t know; we’re talking about your current day job.) You e-mail it to your boss and wait. A few hours later, your boss e-mails you back to say the product didn’t suit her needs. She says she can’t accept it.

Sitting at your computer, you produce your first work product of the day. (What’s the product? I don’t know; we’re talking about your current day job.) You e-mail it to your boss and wait. A few hours later, your boss e-mails you back to say the product didn’t suit her needs. She says she can’t accept it.

I got thinking about that after reading

I got thinking about that after reading