Imagine this: you’re a successful author with a long-running book series. Suddenly the creative well runs dry and your muse wants to end the series and write different stories, with different characters. However, your fans are begging for the series to continue.

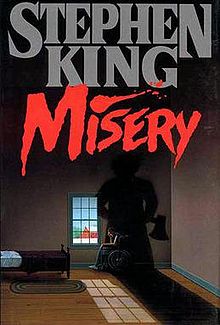

That’s the problem faced by author Paul Sheldon in Stephen King’s novel Misery (1987), so let’s call it the Misery Problem. I mentioned this in a previous blogpost and promised I’d get back to it.

What if the Misery Problem happened to you, in real life? Assuming you didn’t become the victim of an obsessed reader fan who’s also a psychotic nurse, what would you do?

Before I discuss some of your options, I must say this is a problem I’d love to have! After considering it, I’ve come up with the following options:

- Follow Your Muse. End that series that’s become an albatross around your neck. Terminate it by killing off one or more of the beloved characters. You’re tired of those books and you need to move on to other things. Let the fans complain all they want. They’ll adjust.

- Throw Your Fans a Bone. If you really don’t want to disappoint your readers, and if you can stand to write some more stories in the series, but along a different vein, consider:

- A Prequel. Explore what happened before the events of your series.

- An Origin Story. This is a special kind of prequel that relates the story of how your series character(s) got started.

- A Spinoff. Pick an engaging secondary character from your series and write stories about that character. This might work well if you tried to end your series with the death of a main character.

- A Crossover. Consider this if you’ve started a second, unrelated series set in the same time period as the first. In a crossover, characters from the two series meet and interact.

- Please Your Fans. You hate to disappoint your readers, and perhaps you can bring yourself to continue the series. However, you’ve killed off a beloved main character. What to do?

- If you write fantasy, you could conjure up some magical explanation for bringing that character back to life.

- If you write scifi, you’ll need a pseudo-scientific explanation for bringing the character back to life.

- Re-read the scenes where you killed the character off. Is there some wiggle room? Did the character really die, or is survival possible somehow?

Can you come up with other solutions to the Misery Problem? We can only hope it’s a conundrum to be faced someday by you and by—

Poseidon’s Scribe

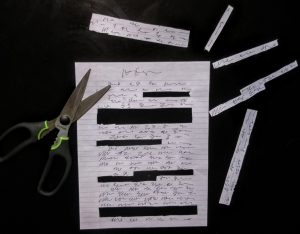

Allow me to define what I mean by censorship. It’s the deliberate alteration of text, without the author’s permission, to make the story less offensive to the censor. This is not what a normal editor does. Editors collaborate with authors to correct errors, to make the book as good as it can be.

Allow me to define what I mean by censorship. It’s the deliberate alteration of text, without the author’s permission, to make the story less offensive to the censor. This is not what a normal editor does. Editors collaborate with authors to correct errors, to make the book as good as it can be.

With Dr. Carl Sagan’s help, I’ve

With Dr. Carl Sagan’s help, I’ve  If you aim to be a writer, able to write convincing tales about characters who are unlike yourself, you must first understand the person from whom these characters will spring.

If you aim to be a writer, able to write convincing tales about characters who are unlike yourself, you must first understand the person from whom these characters will spring.

![Pageflex Persona [document: PRS0000039_00001]](https://stevenrsouthard.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/HidesTheDarkTower-DigitalCover-FINAL2-200x300.jpg)