Next in this series of blog posts is a strange one: Sfumato. I’m blogging about how each of the seven principles in How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci, by Michael J. Gelb, relates to fiction writing. Today I grapple with the fourth principle, Sfumato, a word that means “going up in smoke.”

Gelb’s definition of Sfumato is “a willingness to embrace ambiguity, paradox, and uncertainty.” Although most people prefer knowledge, predictability, and clarity, Gelb contends that Leonardo did not shy away from the gray areas, the question marks, the mysterious, and the absurd.

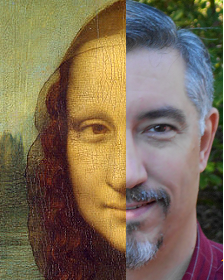

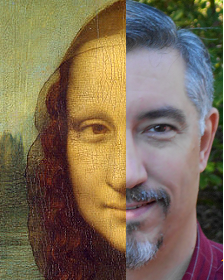

Da Vinci painted beautiful things, but also made many drawings of ‘grotesques’ or ugly human faces. His most famous painting, the Mona Lisa, contains mystery after mystery, including the anonymity of its model. Gelb notes that we discern human mood from the corners of the eyes and mouth, but in the Mona Lisa, Leonardo obscured these areas in shadow, deliberately leaving them vague so we are left to wonder whether she smiles or not.

Da Vinci painted beautiful things, but also made many drawings of ‘grotesques’ or ugly human faces. His most famous painting, the Mona Lisa, contains mystery after mystery, including the anonymity of its model. Gelb notes that we discern human mood from the corners of the eyes and mouth, but in the Mona Lisa, Leonardo obscured these areas in shadow, deliberately leaving them vague so we are left to wonder whether she smiles or not.

Is Sfumato important for a fiction writer? First, let’s define each of its three aspects:

- Ambiguity: something that can be understood in more than one way, allowing for more than one interpretation.

- Paradox: a statement or proposition that, despite apparently sound reasoning, leads to a conclusion that seems senseless, illogical, or self-contradictory.

- Uncertainty: A state of having limited knowledge where it is difficult to choose between two or more alternatives.

Writers make use of ambiguity through symbolism, where one thing may represent something else. Metaphors and similes prove useful to ways to compare the unfamiliar to the familiar, but also leave the story open to interpretation. Often the greatest works of literature contain enough ambiguity to allow generations of critics to argue over meanings.

As for paradox, a writer may employ it for humorous effect, as in Gilbert & Sullivan’s “The Pirates of Penzance,” where a young man thinks he can end his apprenticeship with a band of pirates when he is twenty-one years old, but since he was born on February 29, he’s really only a bit over four. Even when a writer uses paradox in a serious way, it can heighten reader enjoyment by giving the reader something to puzzle over and think about.

Uncertainty is at the center of fiction writing, and comes into play in three levels—the character, the reader, and the writer. Fiction must have conflict, and often it can be an internal conflict for the main character. To heighten the drama of the conflict, it’s necessary to force the character to make a difficult decision. The protagonist’s uncertainty is what makes readers keep on reading.

You must create uncertainty in the mind of the reader as well. If the reader knows what’s coming next, there’s no point in continuing with the story.

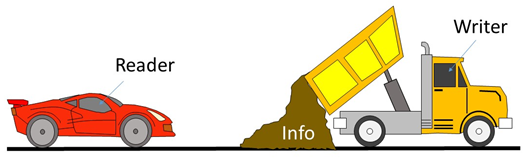

How does uncertainty apply to the writer? I believe this has to do with the tone of the prose. A writer should have something to say, and have a level of confidence in the point she or he is trying to make. I didn’t say ‘certainty;’ I said ‘a level of confidence.’ If you believe you possess the ultimate truths of the universe, the universe will prove you wrong. No reader likes a know-it-all, so I urge authors to advance ideas for consideration, not in a manner that closes the door to criticism.

That’s Sfumato. Now, if you find yourself striding with confidence into areas of smoke, of fog, of murkiness and mystery; if you come to enjoy being ambiguously, paradoxically uncertain, you have no one to blame except Leonardo da Vinci, Michael J. Gelb, and—

Poseidon’s Scribe