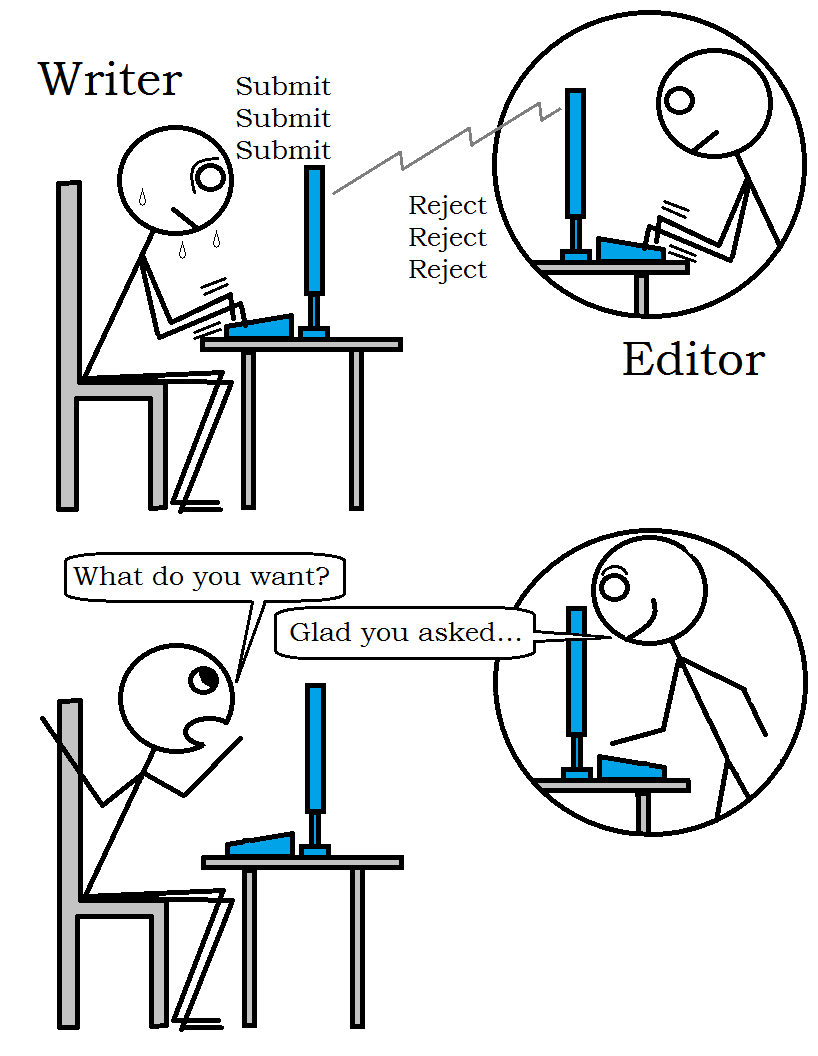

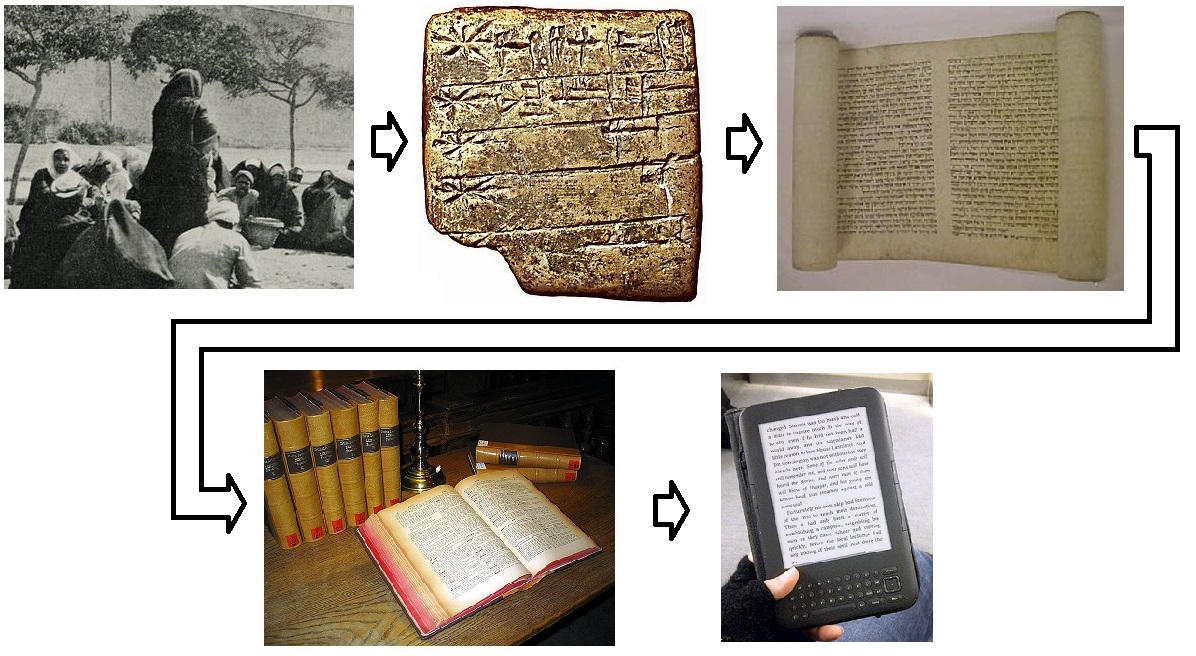

What’s that about a blue pencil? It’s the traditional implement of editors, dating from the days of paper manuscripts. Yes, I’m dealing with editing today—your editing.

That’s right. You must edit your own work before submitting it. Attack it with all the dispassionate, ruthless vigor you can. Hack, cut, and tweak until you fashion it into a story that makes you proud. Only that will make it publishable.

That’s right. You must edit your own work before submitting it. Attack it with all the dispassionate, ruthless vigor you can. Hack, cut, and tweak until you fashion it into a story that makes you proud. Only that will make it publishable.

I’ve discussed editing before, but have learned more since then. I read the book  Getting the Words Right, 39 Ways to Improve Your Writing by Theodore A. Rees Cheney, and recommend it as a great rulebook for editing. The folks at The Write Life blogged about 25 tips for editing, then put those tips into a handy checklist form.

Getting the Words Right, 39 Ways to Improve Your Writing by Theodore A. Rees Cheney, and recommend it as a great rulebook for editing. The folks at The Write Life blogged about 25 tips for editing, then put those tips into a handy checklist form.

That checklist contains many items that aren’t problems for me and left out things that are, and that got me thinking how editing is an individual thing. Each of us has our own quirky flaws and our own strengths. Any checklist I develop must be different from yours. And also ever-changing, as we discover new things to beware of.

Moreover, the ordering of items in that online checklist bothered me. I sought a checklist that started with the big, story-shaping editing aspect, and proceeded to the fine-tuning parts of editing.

Anita Mumm wrote a post describing the four different phases of editing. Developmental Editing refers to the big stuff, including whole sections and scenes, overall style and tone, major characters, plot arcs, etc. Line Editing is all about tackling the paragraphs and sentences, improving their structure and flow, making the work more readable. Copy Editing focuses on punctuation, grammar, and word use. Proofreading is the last check for anything missed in previous edits, and works best when you read your story aloud.

Here’s my editing checklist, provided as a starter for you to modify, altering and tuning it to your needs. I’ve divided it into the four types of editing, and it contains items I’ve found useful for my short stories. Each phase of editing works best when some time has elapsed since you wrote your first draft, ideally weeks or even months. That provides the right emotional distance for a critical editing job.

Developmental Editing

- Choose the best voice for telling the story (first-person or third, close or omniscient)

- Choose the best POV character

- Endure main characters are appealing, relatable, 3-dimensional, not stereotyped

- Ensure each main character has a motivation, a goal, an external or internal conflict, and an epiphany

- Ensure secondary characters are necessary, and still secondary. Should one be promoted to lead?

- Ensure scenes are in the best order for telling the story

- Cut unnecessary sections or scenes

- Ensure each section is about one thing

- Maintain a single tone and style

- Fill plot holes

- Fix story threads that go nowhere

- Pace the action and create tension where appropriate

Line Editing

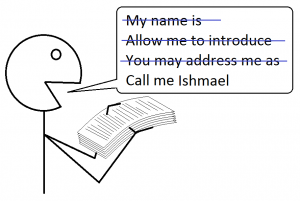

- Craft an irresistible hook

- Make sure sentences vary in length and structure

- Ensure each word in a sentence has a purpose

- Phrase things positively

- Chose simple words, the precise words needed

- Use strong verbs in place of was/is/has/be/etc.

- Phrase sentences in active voice

- Introduce each scene to orient the reader to characters and setting

- Put the reader in the scene by reaching all five senses

- Sprinkle setting descriptions throughout scenes, with the right details

- In each scene, ensure all the dialoguing characters want something

- Let the reader know what the POV character is feeling and thinking

- Ensure characters react to what other characters say and do

- Use appropriate and distinct character dialogue, but don’t overdue accents

- Don’t shy away from “said,” but have characters do things while talking

- Find new ways to word your favorite, overused words and phrases

- Delete or twist clichés

- End each section with a cliff-hangar

- Transition logically and smoothly between paragraphs and sections

- Use, but don’t overuse, repetition for emphasis

Copy Editing

- Use “that” and “which” appropriately

- Delete “that” when you can

- Use commas and periods correctly in dialogue

- Make each adverb earn its place

- Select the correct word (further/farther, continuous/continual, nauseous/nauseated, etc.)

- Find and correct the misspellings the spell-checker missed

Proofreading

- Read the story out loud

- Correct anything that trips you up, throws you out of the story, or sounds odd

Feel free to steal my list and modify it to suit you. Delete things that aren’t problems for you. Add items that your critique group and other editors have commented on in your work. Now you know the one with the cure for those low-down blue pencil blues; it’s—

Poseidon’s Scribe

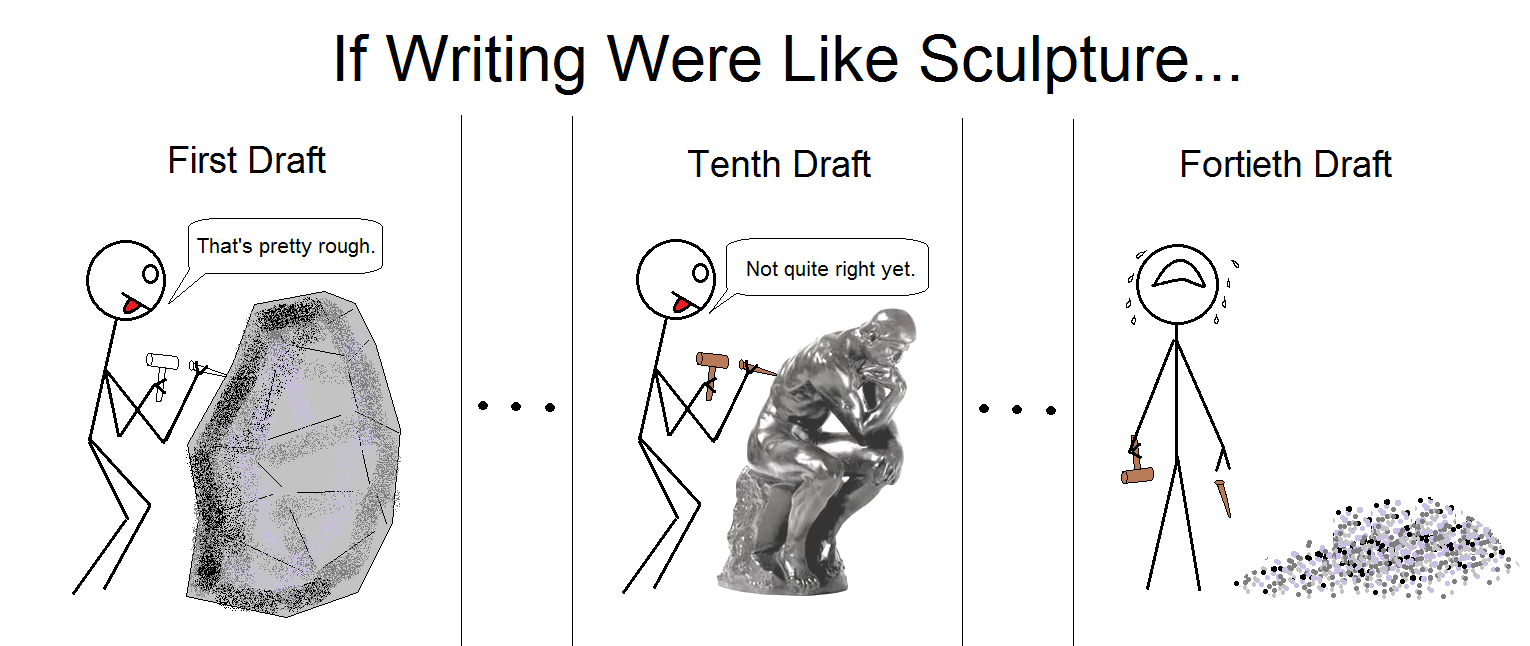

We could seek advice from accomplished authors. Unfortunately, the various quotes I’ve compiled run the gamut from the ‘don’t edit at all’ extreme to ‘seven revisions might not be enough.’

We could seek advice from accomplished authors. Unfortunately, the various quotes I’ve compiled run the gamut from the ‘don’t edit at all’ extreme to ‘seven revisions might not be enough.’