Writers should read. I’m rather organized about it, maybe bordering on anal. This week marks twenty years since I started keeping a log of my reading.

My spreadsheet started in January 2003. Since then, I’ve read 637 books. Fiction comprised 67% of these. Over those two decades, I’ve averaged 12.6 days per book.

In my spreadsheet, I note the date I finished, the title, author, and whether it’s fiction or nonfiction. For text-type books (print or ebook) I enter the number of pages and compute pages read per day. For audiobooks, I note the number of hours and compute the hours listened per day.

For print and ebooks, I’ve read an average of 16.7 pages per day and averaged 31.6 days to finish a book. The average audiobook took me only 6.9 days to complete, listening for an average 1.5 hours a day.

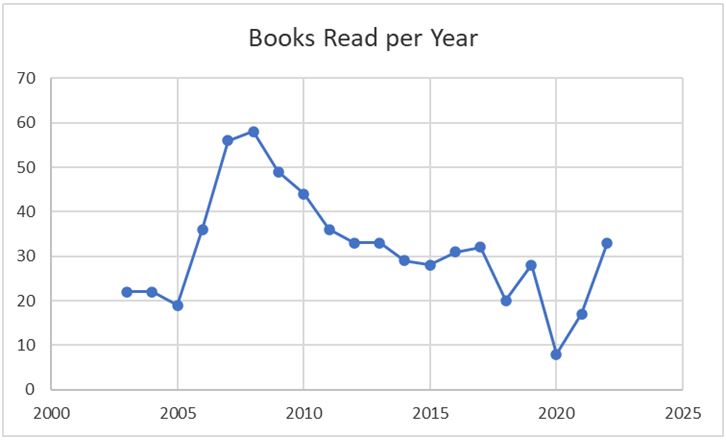

In an average year, I read 31.9 books, but that varied a lot. One year I only read 8, and another year I read 58.

I’ve consumed books in various formats—178 print books, 21 ebooks, 301 audiobooks on CD, 85 audiobooks on cassette (not many of those lately), and 52 downloaded audiobooks. Therefore, I’ve listened to 69% of the books and read the text of the remaining 31%.

If it sounds like I’m bragging, believe me, I’m not. I’m disappointed I didn’t read much more. This is an admission of failure, not a proud boast.

What sort of books do I read? I don’t note the genres in my spreadsheet, but much of the fiction is scifi. In nonfiction, I’m eclectic—all over the map.

In addition to the log, for the past 9 of those 20 years, I’ve posted reviews on Goodreads and Amazon of the books I read. That totals about 244 reviews. I’m not always kind in my reviews, but I try to be fair, noting strengths and weaknesses of each book. If I support other writers by reviewing their work, perhaps some will return the favor. Any review, whether good or bad, can help sales.

I’ve noticed my reading habits changing over the years. I used to read during my commute to and from work, either reading on the subway or listening to audiobooks in the car. I also read on the plane when traveling for work. Since my retirement, I’ve begun reading before breakfast, and still listen to audiobooks when traveling by car and I read on the plane when I fly.

Do you keep a record of the books you read? If not, should you start? Up to you, of course, but let me caution you first. Human nature is such that you get more of what you measure and less of what you don’t. If you start logging your reading, you will read more, but only at the expense of something else you’ll be doing less.

How does my reading data stack up against the average person? According to Gallup, the average American reads 12.6 books per year, the lowest average in 30 years, down from a high of 18.5 in 1999. The Penn Book Center found CEOs read a great deal, with Bill Gates reading about 50 books a year—a good goal.

There’s an app called Basmo that will log your reading for you. I’ve never tried it, but it looks easy to use, and it does all the spreadsheet calculating stuff. Using that app might inspire you to read more.

Without much effort, and with the aid of a log or logging app, you should be able to read much more than—

Poseidon’s Scribe