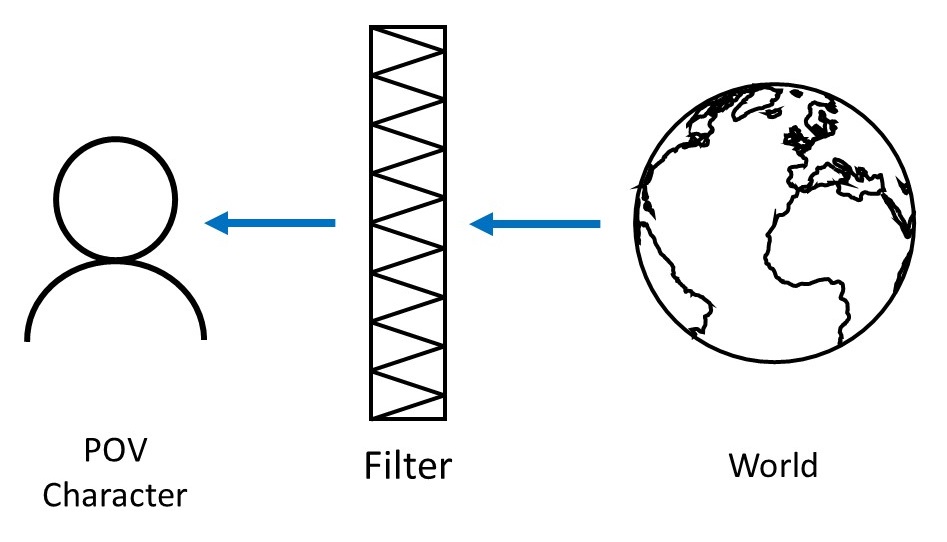

Today I’ll add another set of things you should look for as you edit your writing—filter words.

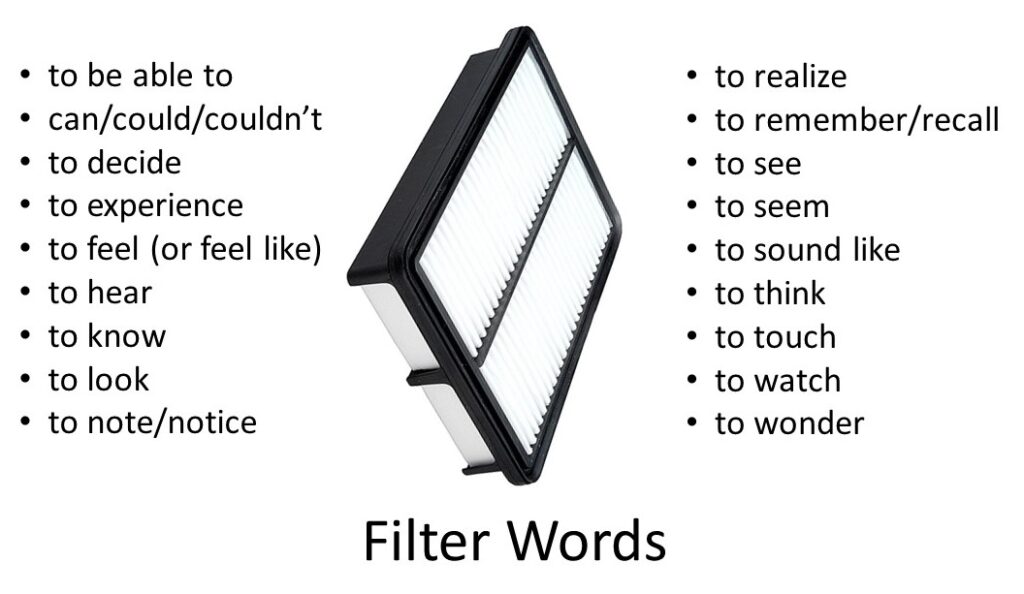

What are filter words? Sometimes called ‘distancing words,’ filter words (or phrases) describe how your point-of-view character perceives and understands the world.

Suppose I wrote this:

Not bad use of senses, but this paragraph tells the reader how Cheryl perceives the world. It reminds the reader who the POV character is.

But what if I’ve already established that earlier? What if the reader knows we’re in Cheryl’s POV and doesn’t need reminding? In that case, the filter words just get in the way. The world’s out there. Plunge your reader into it, right beside Cheryl.

Stronger, bolder writing, it immerses the reader into Cheryl’s world without unnecessary signs stating we’re in Cheryl’s head.

Sure, there are times when filter words are appropriate. Often it’s necessary to inform the reader whose head we’re in, such as the point just after a POV shift. On occasion, the whole point of a given written sensation is to be clear about who’d experiencing it. Sometimes it just fits better to use a filter word. Like most things in writing, this isn’t a hard-and-fast rule.

You can read more about filter words at this post by Suzannah Windsor Freeman, this one by H. Duke, this one by editor Louise Harnby, this one by the staff at Invisible Ink Editing, and in the book The Author’s Checklist by Elizabeth K. Kracht.

For now, please excuse me. I’ve got to go hunt down and delete a bunch of filter words from the rough drafts of—

Poseidon’s Scribe