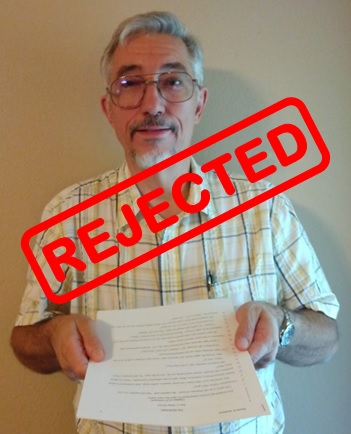

Interesting fact—over the years, I’ve submitted stories 441 times, and in all of the responses to all of those submissions, I’ve never been rejected. Hard to believe? Consider this—no matter how many times you submit your writing for publication, you will never be rejected either.

To clarify, my stories have been rejected plenty of times. Yours might be rejected as well. But I, as a person, have never been rejected by any editor. Nor will you.

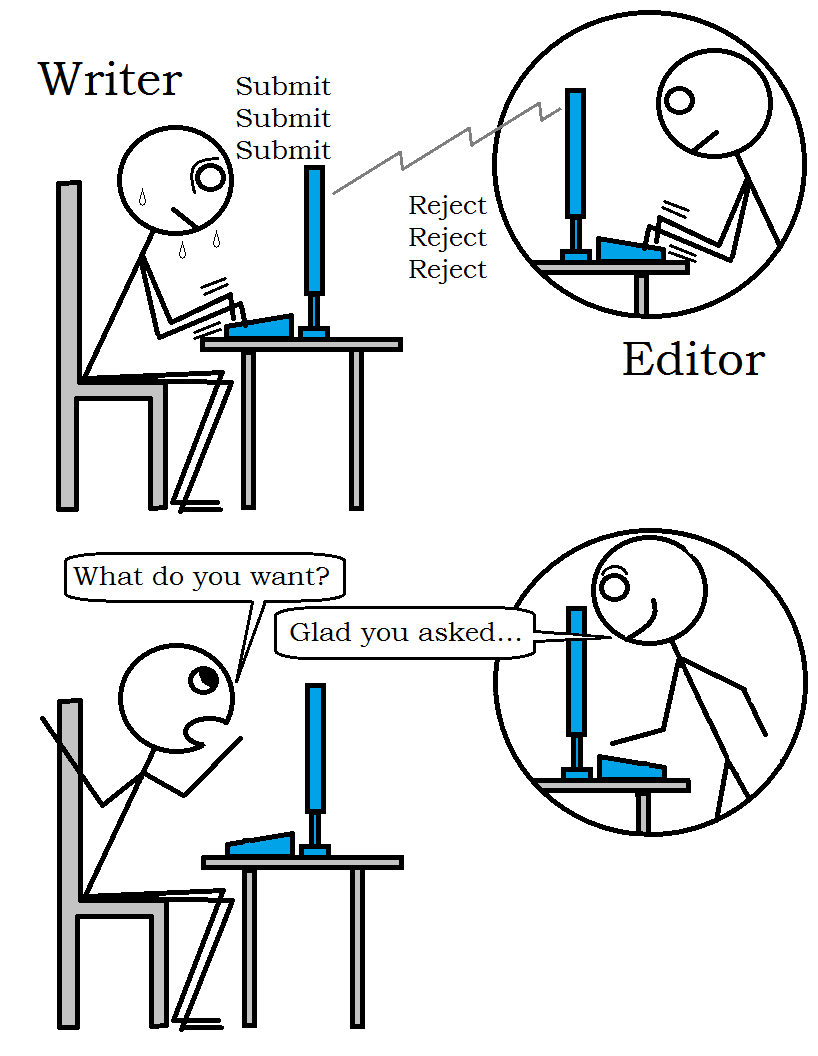

When one of your stories gets rejected, it sure feels like the editor is rejecting you, doesn’t it? It’s like the editor’s saying, ‘You’re not good enough for my publication. You really aren’t a very good writer. You ought to quit now and consider doing something else with your time.’

Editors never say that. Nor do they mean it. But we writers can’t help but think that’s what they mean. After all, we think, I just wrote something from the heart, from the deepest part of my soul. I am the story, and the story is me. When you reject it, you reject me.

In dealing with this conundrum, you’ve got two options to choose from:

- You can identify with your stories in a personal, intimate way. When an editor rejects one of your stories, you can regard it as a rejection of your very being. You’ll have to find some way of coping with that (see below).

- You can place some emotional distance between yourself and your stories. They’re not you and you’re not them. They’re good, and you’re proud of them, but they’re a product of you, not the very essence of you. A rejection of a story is nothing more than a minor setback. It doesn’t constitute a condemnation of you as a person. Your identity as a writer remains intact.

Though I practice Option 2, I’m not sure that’s best. It can lead to a disinterested approach to writing—’It’s just a story, after all. It’s not me. Who cares if it gets rejected?’

Option 1, however, reminds me of the quote attributed to Ernest Hemingway—“There’s nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and open a vein.” That attitude calls for baring your soul using words, pouring out your essence into every story. Perhaps Option 1 could result in the best, most masterful writing you can do.

If you choose Option 1, how do you deal with rejection? You’re in for a rough time when an editor rejects (what you consider to be) you. At a minimum, alcohol may get consumed and perhaps your forehead will bang into a wall a few times. I hope nothing worse occurs.

It seems likely that, for Option 1 writers, rejection becomes less soul-crushing after the tenth, or the hundredth time. I hope so, even if only for the sake of minimizing wall damage.

Perhaps wisdom lies in a sort of balance between Option 1 and 2. You could maintain a close relationship, an identity, with your stories, while growing a hard shell when it comes to others’ opinions. You’re going to need a thick skin at some point anyway, even after acceptance, when critical readers leave scathing comments.

Whichever option you choose and however you deal with rejections of your stories, it remains true that you will never get rejected, and neither will—

Poseidon’s Scribe