Think you can take criticism well? How about when people you trust denigrate something you worked very hard on, and are proud of? Aye, there’s the rub, don’t you think?

I’ve often discussed critique groups and how much I value them (here, here, and here), but today I thought I’d help you prepare for receiving criticism at your critique group meeting. Believe me, the first few meetings will be tough when they’re poking holes in your story. At such times, it’s difficult to remember that group members are (1) being honest, (2) criticizing your work, not you, (3) on your side and want you to succeed, and (4) telling you what readers and editors would think.

I’ve often discussed critique groups and how much I value them (here, here, and here), but today I thought I’d help you prepare for receiving criticism at your critique group meeting. Believe me, the first few meetings will be tough when they’re poking holes in your story. At such times, it’s difficult to remember that group members are (1) being honest, (2) criticizing your work, not you, (3) on your side and want you to succeed, and (4) telling you what readers and editors would think.

Are you supposed to just sit there and take it? In a word, yes. The very best thing you can do is be silent and listen. I don’t mean pretend to listen while thinking of what you’ll say next. I mean really listen. Get outside yourself, beyond your ego, and see your work through the critique group members’ eyes. Suspend your doubts about their intelligence and assume, at least for the moment, that they might just be right.

You’ll feel a powerful temptation to explain why you wrote something the way you did, to help these deluded group members comprehend the brilliance of your prose which they somehow missed. You’ll even want to defend your story against these attacks, and possibly argue with these formerly intelligent friends who’ve suddenly caught an ignorance virus.

After all, who are they to tell you your story’s hook is boring; your protagonist lacks depth; your plot doesn’t make sense; your setting is like a room with plain, white walls; and the story’s central conflict could have been resolved by a first grader in seconds? Worse, the passages they’ve recommended cutting are your favorite parts.

No, it won’t be easy to sit there and take it. But the old adage ‘you can’t learn with your mouth open’ is true. So you need to develop a thick skin, grow up to adulthood, and listen. And when you’ve suffered their slings and arrows (without taking arms against that sea of troubles), then what? Then, my friend, you will thank these critique group members. Yes, you will express sincere gratitude for the help they’ve provided.

At what point, exactly, did they provide help, you ask? How can I call it help when your manuscript lies twitching and bleeding on the floor, unloved by all but you? Here are just some of the ways your group members assisted you:

Free of charge, they’ve given you—

- a fresh perspective from which to see your work, without the rose-glasses filter of your biases;

- information you can use to decide whether to change your manuscript, since changes are still your decision, but now these decisions will be based on facts, not guesses, about how readers will likely react;

- an improved ability to endure criticism. More negative criticism will come later, from editors and from readers. But those later critiques won’t upset you, thanks to the way your critique group prepared you.

Here’s an excellent blog entry by Joanna Penn on the subject of taking criticism, and she offers even more thoughts.

So, has this blog entry made you a bit “nobler in the mind?” As always, please leave me a comment with your thoughts. My next critique group meeting is coming up soon. My fellow group members will know then whether “practice what you preach” is advice well followed by—

Poseidon’s Scribe

True, Leonardo da Vinci was an anatomist, architect, botanist, cartographer, engineer, geologist, inventor, mathematician, musician, painter, scientist, and sculptor. Arguably he was the greatest genius of all time. But…he never wrote fiction.

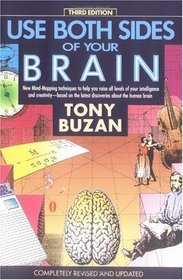

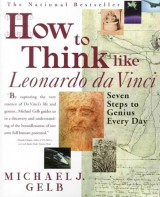

True, Leonardo da Vinci was an anatomist, architect, botanist, cartographer, engineer, geologist, inventor, mathematician, musician, painter, scientist, and sculptor. Arguably he was the greatest genius of all time. But…he never wrote fiction. In his book

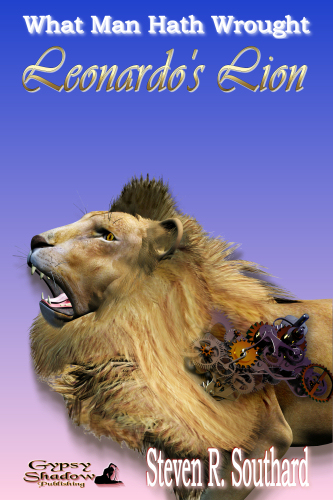

In his book  At this point, I can’t resist a personal plug. Leonardo da Vinci is such a fascinating historical figure, I wrote a story about the mechanical automata lion he constructed for the King of France. Had that been all da Vinci did, it would have been achievement enough, far beyond the norm of the day, but it’s barely a footnote in any list of his accomplishments. My story,

At this point, I can’t resist a personal plug. Leonardo da Vinci is such a fascinating historical figure, I wrote a story about the mechanical automata lion he constructed for the King of France. Had that been all da Vinci did, it would have been achievement enough, far beyond the norm of the day, but it’s barely a footnote in any list of his accomplishments. My story,  experience is based solely on twenty years of being in small, amateur, face-to-face critique groups; not writing workshops, classes, or online critique groups; so the following advice is tuned to that sort of critique.

experience is based solely on twenty years of being in small, amateur, face-to-face critique groups; not writing workshops, classes, or online critique groups; so the following advice is tuned to that sort of critique.