You’ve heard of plot devices, but do you know what they are? Are they good or bad? Can you name any? For answers to these questions, you’ve come to the right blog post.

From www.snappygoat.com.

Before we can define the term ‘plot device,’ let’s review what a plot is, and how a writer develops one. A plot is a sequence of events in a story, events connected by cause and effect. The writer aims to construct this sequence such that it accomplishes at least the following goals:

- illustrates the human condition,

- introduces a conflict and depicts the protagonist striving to resolve it,

- grabs and sustains the reader’s attention,

- leaves the reader with a powerful emotion at the end, and

- reflects believable cause-and-effect connections.

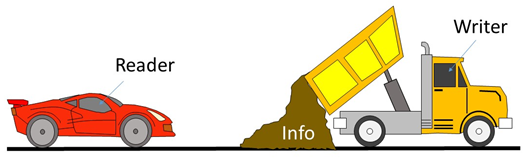

If you’re a writer crafting your story, it can be difficult to achieve all these purposes successfully. Often a complication develops. Unlike the reader, you know the story’s end and you’re aiming for that point. You might hit a snag where the next logical event in a cause-effect chain will not result in your desired story ending. To put it another way, to get to the end you want, something illogical has to happen. Your options at this point include:

- re-writing earlier sections to make the strange cause-effect chain believable

- re-thinking the ending of the story

- introducing a plot device to get past the difficulty

Often the first two options are undesirable, so that drives writers to the third—the plot device.

The ‘device’ in the term ‘plot device’ refers to its original definition of a plan, scheme, or technique, not its modern connotation of a mechanical or electronic gadget.

Here are some examples of plot devices:

- Bogus alternatives. This one comes from the Turkey City Lexicon. Sometimes, to make the plot work, the author needs a character to take an uncharacteristic action. An inexperienced author will walk the reader through the character’s mental list of options, rationalizing why the character chooses one action and not the others. This interrupts the story’s pace, pulls the reader out of the story, and is unnecessary.

- Deus ex machina. A surprise entity comes out of nowhere to save the protagonist from a plot problem. Let’s see, Jules Verne thinks, I’ve got the title, The Mysterious Island, and I’ve got my heroic castaways who survive mostly by their wits, except sometimes they need outside help. I know! I’ll let them be aided by an unknown benefactor, later revealed to be Captain Nemo!”

- Idiot plot. This is another one from the Turkey City Lexicon. If the writers plot problem is serious, one solution would be to set the story in the land of idiots, which would explain any unusual action taken by any character. They can all act to further the author’s plot, no matter how irrational any character’s actions seem.

- MacGuffin. The protagonist pursues an object, believing it to be important, though (to the reader) another object could work as well. “Listen, Dashiell, I like novel, but can we change this Sicilian Vulture statuette to something else…say, a Maltese Falcon?” “Okay, sure.”

- Plot voucher. Someone gives the protagonist an object that turns out to be the one thing needed later to get the hero out of a bad situation. “Holy plot device, Batman, why are you loading bear repellent in your utility belt?” “Better safe than sorry, Robin.” <later> “Holy Ursa Major, Batman! We’re surrounded by hungry grizzlies!” “Yes, lucky thing I happened to bring…”

- Red herring. Anything used by the author to distract the reader’s attention away toward the unimportant and away from the important. Most frequently used in mysteries to lead the reader toward an incorrect conclusion. The term dates from the use of strong-smelling fish to divert hounds from chasing the hare. I haven’t read Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, but I understand it contains a character with an Italian name that translates as “red herring.”

- Shoulder angel. A plot device used in visual media such as comic books, animated cartoons, or screenplays to illustrate a protagonist debating with her conscience, sometimes accompanied by a devil (temptation) on the other shoulder.

From the tone of my post, you’re probably concluding that plot devices are bad, and it’s best not to use them. I’m not going to take that stance. Most writers try not to need them, but end up using them from time to time. The trick is to write well enough that readers get so swept up by your story that they don’t notice you’ve used a plot device.

To sum up, what is the price of that nice plot device, as I so poetically asked in the post’s title? The answer is, it’s free to use, but if you don’t use it well, readers won’t enjoy your story. Take it from—

Poseidon’s Scribe