The spread of the COVID-19 coronavirus has got us all thinking. Each of us is reacting in his own way. As a writer, my mind turns toward fiction possibilities.

Please don’t take this post as some attempt to minimize or make light of this contagious and deadly disease. The numbers of infected and dead continue to mount as this new virus spreads around the world. Nobody knows how bad this coronavirus will get. Though panic may be unwarranted, so is blind optimism.

So far, I’m not showing any symptoms and am not under quarantine, neither the imposed nor self-directed kind. To my knowledge, that’s also true of everyone I know well. I’m not blogging about quarantines due to any personal experience, but merely because the topic is timely and it interests me as an observer of society.

COVID-19 is causing some changes in our behavior. For the most part, we’re all washing our hands more often and more thoroughly. We’re travelling less, and going to fewer well-attended events. We’re practicing ‘social distancing,’ and greeting others with fist or elbow bumps. We’re staying in our homes more and connecting with each other virtually.

When TV journalists conduct video interviews of symptom-free people who’ve been quarantined out of caution, the people all say they’re binge-watching movies and playing games to pass the time. (Not reading books? Come on!) But they feel lonely and isolated. They want the two weeks to be over.

That’s understandable. We’re social animals. We gain comfort from the close presence of others. If we now must view others as potential bringers of disease, that sets up an internal conflict, a tension between self-preservation and a need for acceptance.

For most writers, a symptom-less quarantine wouldn’t be so bad. Writing is solitary anyway, and necessary social interaction represents an interruption of the writing process. To some extent, writers practice a quasi-quarantine all the time.

Perhaps because of their self-imposed isolation, authors sometimes write about disease pandemics. Early examples include The Decameron (1353) by Giovanni Boccaccio and The Last Man (1826) by Mary Shelley.

More recent novels about pandemics are The Plague by Albert Camus, The Andromeda Strain by Michael Crichton, and The Stand by Stephen King.

All these works depict horrible results after the disease has run its course. Few novels (except The Plague) show the effects of quarantine, of forced separation.

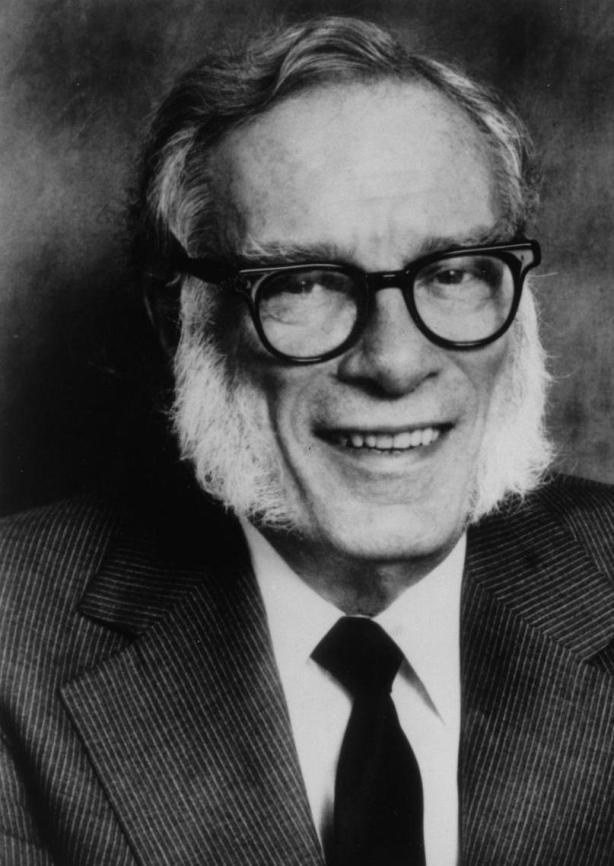

One extreme fictional example of human separateness, though not involving disease, is The Naked Sun by Isaac Asimov. In it, citizens of the planet Solaria grow up detesting the physical presence of other humans. They don’t mind robots, but can only talk to other people through holographic communication, a sort of 3-D version of Skype.

Could COVID-19 or some later, more deadly virus, force us to behave like Solarians, alone in our homes, communicating only by email and text, with drones delivering all our supplies direct from robot factories? What would that isolation do to our psyches, to our instincts for close contact?

There’s your next story idea, free of charge. You may thank me for it, but not in person. Alone (with my spouse) in quasi-quarantine, I’m—

Poseidon’s Scribe