Together, you and I have arrived at the end of this seven-part series of posts. We’ve been working our way through the principles in Michael J. Gelb’s wonderful book How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci. For each principle, we’ve been exploring how it relates to fiction writing.

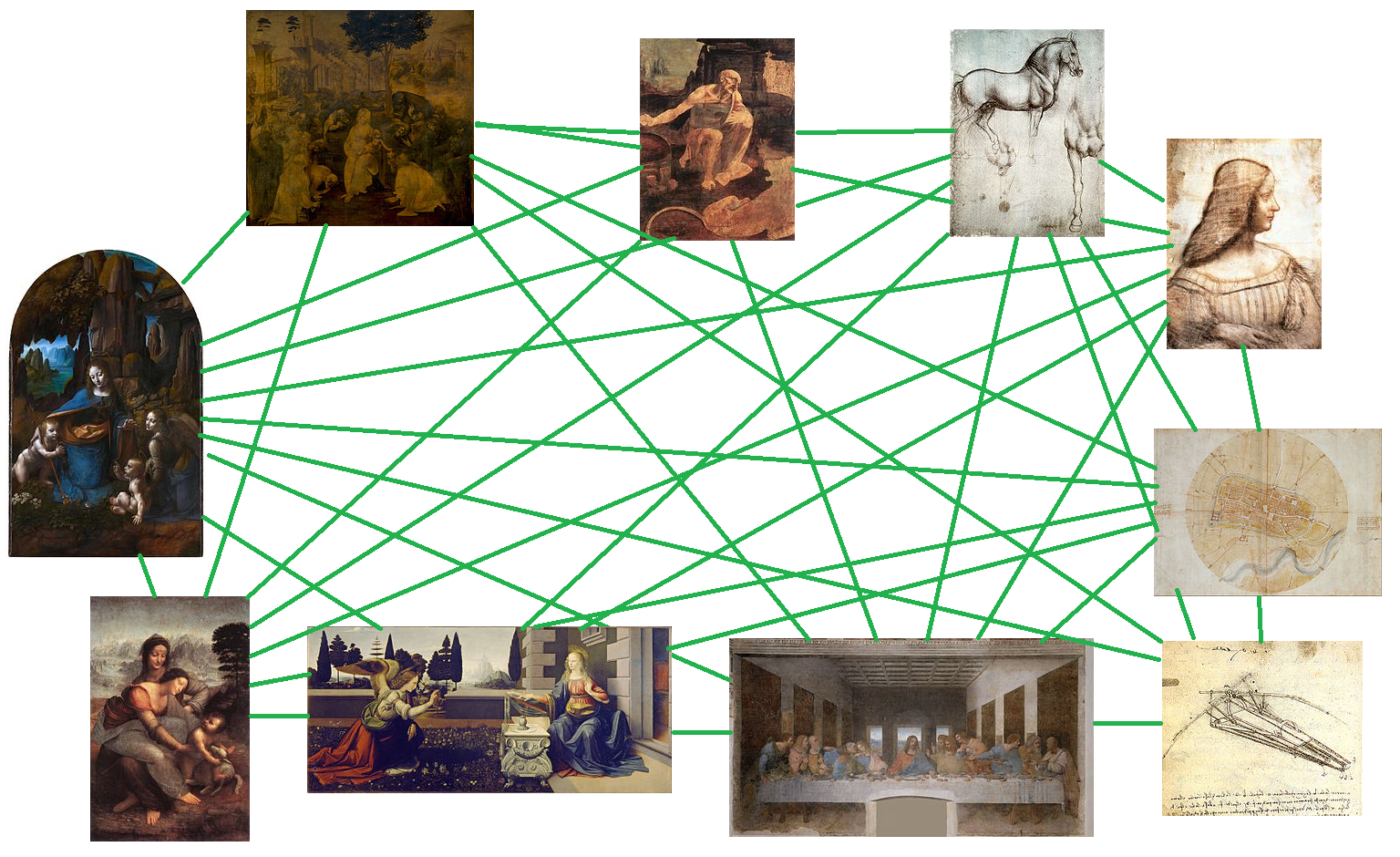

The last principle is Connessione: a recognition and appreciation for the interconnectedness of all things and phenomena—systems thinking.

Leonardo had a fascination with the connections between things. He’d study how a tossed stone caused expanding circular ripples in water. He wrote, “The earth is moved from its position by the weight of a tiny bird resting upon it.” His notebooks were a disorganized, chaotic stream of consciousness, as if his mind would flit from one thing to a seemingly unrelated thought. In a strange echoing of what we might consider Eastern philosophy, he wrote: Everything comes from everything, and everything is made out of everything, and everything returns into everything.”

Leonardo had a fascination with the connections between things. He’d study how a tossed stone caused expanding circular ripples in water. He wrote, “The earth is moved from its position by the weight of a tiny bird resting upon it.” His notebooks were a disorganized, chaotic stream of consciousness, as if his mind would flit from one thing to a seemingly unrelated thought. In a strange echoing of what we might consider Eastern philosophy, he wrote: Everything comes from everything, and everything is made out of everything, and everything returns into everything.”

In what ways should a writer of fiction embrace the principle of Connessione? Here are some that occur to me:

- When you’re thinking of plot ideas for stories to write, look for separate ideas from the world around you and connect them. To pick just three examples of this, consider how Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games series combines the ideas of TV reality shows and war; how Stranger in a Strange Land by Robert A. Heinlein combines Tarzan, Jesus, and Mars; how Herman Melville’s Moby Dick combines whaling and obsession.

- Think of the interconnections between characters within your stories. For characters A and B there are (at least) four connections: how A feels about B internally, how A behaves toward B externally, and the same internal feelings and external behavior of B toward A. Now imagine three, four, five, or more major characters and convey, in your story, the rich web of interconnectedness between them all. This alone will be the subject of a future blog post.

- Your stories have an internal, systemic structure. They are a connection of related parts. The chapters (or sections) are themselves composed of scenes, and build on each other to form the integrated whole of the story.

- The story element of theme is a connection between concrete things in a story to abstract ideas in real life. Similarly, the techniques of metaphor and simile are connections in the form of comparisons—relating something you’re describing in your story to something familiar or understandable to the reader.

See? If you write fiction, you must embrace the notion of Connessione to some extent. In fact, it helps to practice all seven principles— Curiosità, Dimonstrazione, Sensazione, Sfumato, Arte/Scienza, Corporalita, and Connessione. Perhaps you’ll not become as well remembered or universally admired as da Vinci, but you can think like him, and write fiction as he would have. That’s the aim of—

Poseidon’s Scribe

experience is based solely on twenty years of being in small, amateur, face-to-face critique groups; not writing workshops, classes, or online critique groups; so the following advice is tuned to that sort of critique.

experience is based solely on twenty years of being in small, amateur, face-to-face critique groups; not writing workshops, classes, or online critique groups; so the following advice is tuned to that sort of critique.