Metaphorically, we all wear many hats. That is, we have many roles in life. For some of us, one of those roles is Writer. Let’s explore that.

I got the inspiration to write this post from this one, by Brian Feinblum.

You started your life with the role of daughter or son, and may still have that role. Maybe you’re a sister or brother, spouse, parent, employee, grandparent, volunteer. Most likely you’re a citizen, too. These are all examples of possible roles in your life. When you think about it, you probably have a good number of roles, between two and twenty or more at any one time. If you care about being a good person, you work hard to fulfill all of your roles well.

Problem is, it’s a balancing act. Each role requires time, and you only have so much of that. They all compete for your precious hours. That requires you to divide your time, keeping each plate spinning as best you can.

On occasion, you must devote nearly full time to one role and set the others aside. When someone you love becomes sick or injured, for example, your role involving that person must take precedence and the others must wait until the emergency is over. When there’s a major project at work, your employee or boss role predominates until the project is done.

When you must set several roles aside like that, the writer role is especially problematic. It’s a self-assigned role, based on your love of an activity, not a person. Unlike the role of spouse or employee, if you neglect your writing, it will patiently wait in the background, not complaining or otherwise reacting. If you set it aside for weeks, months, or years, there will be no adverse consequences.

Oh, your muse may squeal a bit. That voice inside, the one urging you to write, will yell loudly for a while. Eventually, that voice will fade and you’ll hear only an occasional whimper.

However, if you’re lucky enough, if life’s other roles allow you the time, you’ll remain a writer. You’ll carve out the time as best you can.

There are ways to make the best use of that time. Although the general guidance I’ll present below works for all your roles, I’m focused on your writer role.

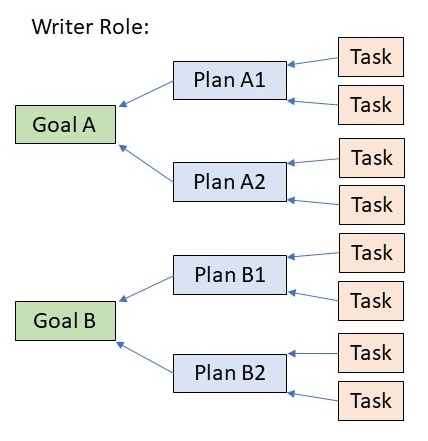

In his book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, Stephen R. Covey recommends you take each role and set long-term goals, then make shorter term plans to achieve those goals, then set aside time each week to schedule the most important tasks to advance the plans.

The goals and plans don’t all have to be writing projects (stories). The tasks that support them can also include:

- attending writing or genre conferences,

- reading books about writing,

- taking writing classes,

- self-assigned writing assignments to work on particular weaknesses,

- researching aspects of writing you’re curious about or need help with,

- critiquing other writer’s works,

- reading classic fiction,

- increasing your online footprint,

- blogging,

- updating your website,

- getting an author photo taken, or

- hundreds of other ideas that might help you achieve your writing goals.

This needn’t be a complex or overly organized process. Mold it to suit you.

Uh oh. Another role is beckoning. Time to take off the Writer hat of—

Poseidon’s Scribe

A strategic plan is a detailed blueprint of how to achieve that mission. It assigns intermediate actions to complete, and dates when each action is to be done. It is a logical progression of steps toward the goal. It is achievable and actionable.

A strategic plan is a detailed blueprint of how to achieve that mission. It assigns intermediate actions to complete, and dates when each action is to be done. It is a logical progression of steps toward the goal. It is achievable and actionable.