Continuing the tradition established last year, I’ll make some predictions for science fiction for the coming year.

First, however, I have an update on Twenty Thousand Leagues Remembered, the upcoming anthology I’m co-editing along with the talented writer and editor Kelly A. Harmon of Pole to Pole Publishing. We’ve moved the opening date for submissions to January 10. Click here for details.

Back, now, to the prognostications. Abandoning my crystal ball, which didn’t work so well, I’ve since mastered the technique of Tasseography, or reading tea leaves. Let’s peer into the cup and see what the leaves reveal:

- Partisan Politics. SciFi will become more political in this U.S. election year. With the citizenry becoming increasingly partisan, authors will show their political biases and opinions in their stories. Stories will increasingly be either left/liberal or right/conservative. This trend disturbs me, but I have to call ‘em as I see ‘em.

- Post-Apocalypse. With the decline and death of the dystopia will come the birth of a more hopeful and positive future. We’ll see more stories of civilizations rising from the ashes of past global destruction.

- Time Travel. There are plenty of time periods left to explore, many with subtle lessons for us today. Despite the risk of paradox, authors will give us more time-traveling protagonists heading off to the past or future. Most of these stories will involve romance to some degree.

- Climate Fiction. CliFi will remain a strong sub-genre, with authors exploring humanity’s influence on the Earth’s climate. I predict most such stories will either deal with human attempts to fix the climate before a catastrophe or will take place after a climate catastrophe.

- LBGTQ characters. More protagonists and other major characters will be part of the LGBTQ spectrum. Within these fictional worlds, the cisgendered characters will respect and admire the LGBTQ main characters, not ostracize or mistreat them. Other related works will continue to take place in transhuman, post-gender worlds.

- Strong Female. The damsel in distress is dead. During the last decade or two, she’s been replaced by the Strong Female. This woman is strong in the sense of being fierce, capable, and not dependent on men. Though by now she’s a stock character, SciFi authors will continue to explore various subtleties and nuances of the Strong Female in 2020.

- Star Wars Reaction. With the completion of the triple trilogy “Skywalker Saga” in 2019, authors will pen stories reacting to all things Star Wars. In 2020, I anticipate stories satirizing and otherwise mocking aspects of the George Lucas-created franchise, and probably other SciFi fantasies trying to fill the void by launching Star Wars variants.

- Afrofuturism. Authors in 2020 will weave tales comporting with Afrofuturism 2.0 and Astro-blackness. Audience reaction to the 2018 film Black Panther demonstrated a strong enthusiasm for works merging the themes of the African Diaspora with high technology.

- Boomer Lit. I see some SciFi in 2020 examining baby boomer themes. This will include stories with older protagonists, as well as stories with strong 1960s nostalgic references.

At the end of 2020, I’ll make every effort to assess these predictions, as I did for my 2019 prophecies. Yogi Berra said, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future,” but I have confidence in the tea leaves, so you should have confidence in the prognostication prowess of—

Poseidon’s Scribe

“After the Martians” takes place in the world of Wells’ story, but sixteen years have passed since the alien attack. In my tale, humans make use of the Martian technology, especially the fighting machines, to fight World War I.

“After the Martians” takes place in the world of Wells’ story, but sixteen years have passed since the alien attack. In my tale, humans make use of the Martian technology, especially the fighting machines, to fight World War I.

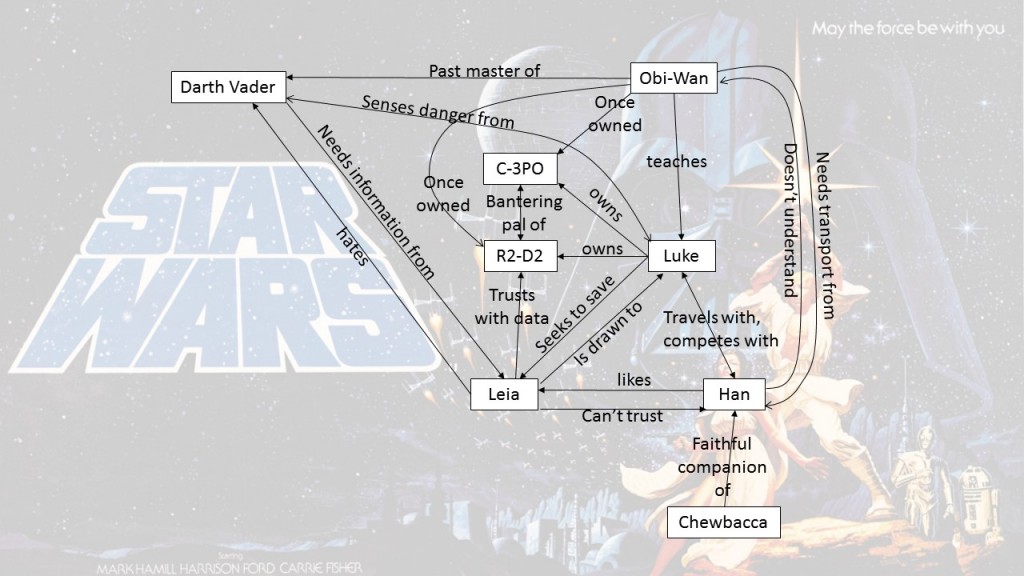

The one I’m showing here, for the first Star Wars movie, A New Hope (Episode IV), is for illustrative purposes only and is not complete or necessarily accurate. My only intent is to show one possible example for a case familiar to most readers. To see many other sample Character Relationship Maps, do an Internet search for that term and click on images.

The one I’m showing here, for the first Star Wars movie, A New Hope (Episode IV), is for illustrative purposes only and is not complete or necessarily accurate. My only intent is to show one possible example for a case familiar to most readers. To see many other sample Character Relationship Maps, do an Internet search for that term and click on images.