I heard you’d like to write a novel. That’s the word on the street, anyway. As they say, writing a novel is a one-day event. (As in, ‘one day, I’ll write a novel.’)

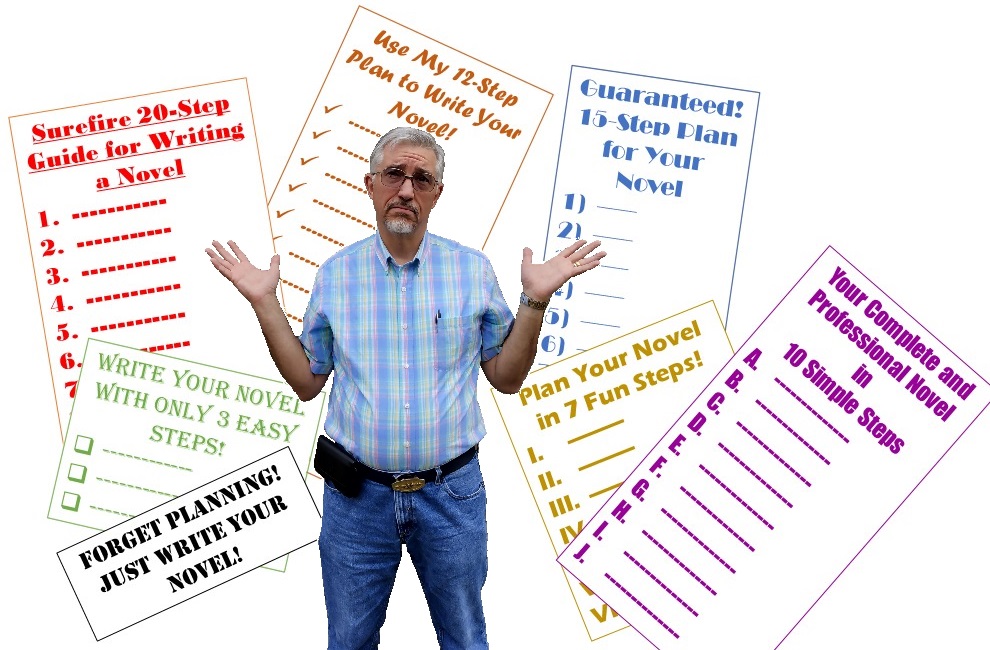

No, you’re more serious than that. You’re going to do it. For such a big undertaking, maybe you should have a plan. Lucky you, the internet can provide one. Wait, more than one. Way more. Uh-oh.

There’s the 3-Step plan by Stephanie Gangi, the 7 Steps for planning a novel by the Reedsyblog staff, the 10-Step Plan by The Writers Bureau staff, the 12-Step Guide by Jerry Jenkins, the 15-Step Plan by the Reedsyblog staff, the 20-Step Guide by Joe Bunting, and the idea of forming no plan at all by Maria Mutch.

That narrows it down. We know there are between zero and twenty steps for writing a novel.

To me, all those plans look good, with many common elements among them, just some differences in emphasis and terminology.

Face it, some people need plans, step-by-step methods that have worked for accomplished authors. Other people hate plans, since they seem too rigid and stifling. Still others don’t mind plans so much, but prefer that the plan emerge as the project itself matures.

Whatever works for you. Emphasis on works. If your organized, detailed plan sits there and intimidates you into inactivity, that’s not working. If your lack of a plan leaves you unsure where to start, that’s not working. If your chosen method results in less than your best creation, well, you can do better.

For my novel in progress, I’m going with the Snowflake Method developed by Randy Ingermanson. It’s got 10 steps or so, and is similar to the 10-Step plan by The Writers Bureau mentioned above.

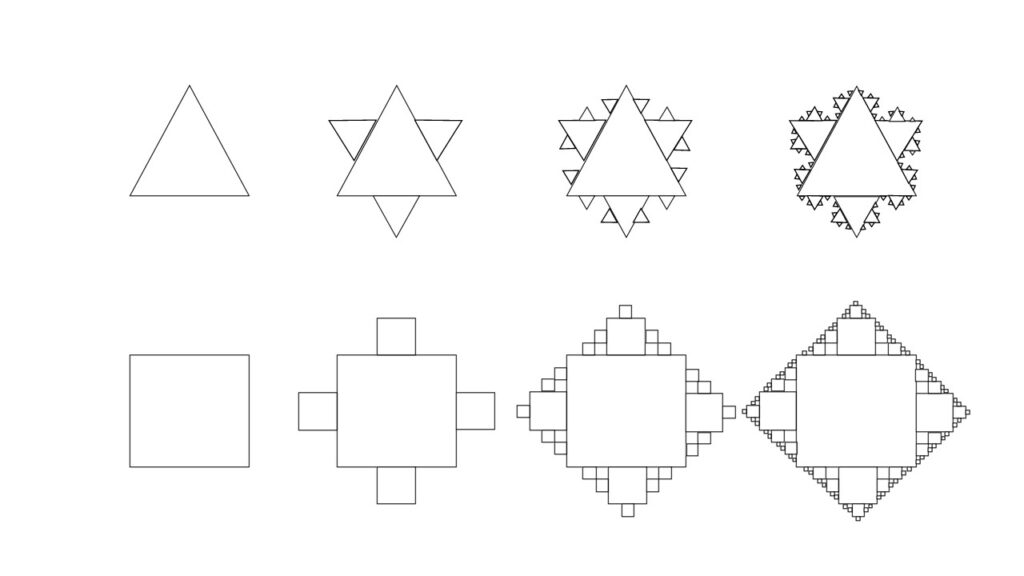

It’s not so much about actual snowflakes, but more about how you’d create a fractal snowflake. You’d start with a basic shape—a triangle or square—and add more detail as you go. That makes sense to me, and I’ve used an abbreviated form of the technique for years in creating my short stories.

They’ve given us a brand-new year to work with. It’s as good a time as any to start. Choose your plan, or no plan at all, and write that novel you’ve been dreaming about. I’ll read yours if you’ll read the next one written by—

Poseidon’s Scribe

Since humorous writing is so tough to get right, why don’t we forget the whole thing? For one, if we can manage to tell a funny story, readers like it. An amusing tale lifts them from the gloomy tedium of their dreary lives, the poor things. Think of it as a public service, kind of a ‘clown-author saves the world’ idea.

Since humorous writing is so tough to get right, why don’t we forget the whole thing? For one, if we can manage to tell a funny story, readers like it. An amusing tale lifts them from the gloomy tedium of their dreary lives, the poor things. Think of it as a public service, kind of a ‘clown-author saves the world’ idea.